The maxim “you can’t build your way out of traffic” holds true in Santa Clara County as much as anywhere. During peak hours, cars inch slowly on highways and arterials that criss cross the South Bay. Billions of dollars in highway improvements, many funded by local sales taxes, haven’t prevented recurring traffic jams. But billions of dollars of investment in a light rail and bus system haven’t yet made transit a viable option — because land uses have not been coordinated with transit investments. Countywide, 87 percent of people get to work in a car and only about 3 percent use transit — numbers that haven’t budged in more than 50 years.

SPUR recently published the report Freedom to Move: How the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority Can Create Better Transportation Choices in the South Bay, which outlines strategies for how VTA can accelerate the shift to a more sustainable and effective transportation system. VTA is a large and sophisticated multi-modal organization led by 15 cities and the county. The agency runs VTA transit, is building the BART extension to Silicon Valley, designs and builds highway projects and is implementing the expansive Silicon Valley Express Lanes highway pricing project. VTA is one of the partners that funds Caltrain, the Capitol Corridor and the Altamont Commuter Express rail services.

How will people get around the county in the future? Santa Clara County, home to Silicon Valley, houses one-fourth of the region’s residents and one-fourth of its jobs. Its population is poised to grow by 36 percent (641,830 new residents) and the number of jobs is expected to grow by 33 percent (303,270 new jobs) by 2040.[1] The county has been deeply shaped both by the car and growth during the highway era; we probably won’t wake up one day to a South Bay free of traffic. Nor will the spread-out subdivisions quickly transform into the walkable streetcar landscape of older cities. Nonetheless, SPUR believes that we can make the options of cycling, walking or transit work.

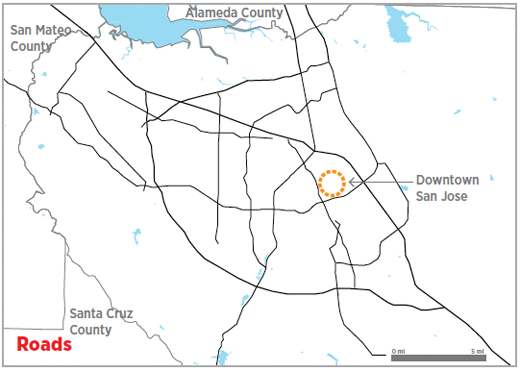

In particular, VTA and its member agencies, along with private partners, can create real transportation choices by continuing to focus on networks. The greatest shifts in auto and transit usage have been achieved in places with highly interconnected transit networks that are linked with safe and direct walking and bicycling networks.[2] The South Bay has already developed a robust road and parking network, making it comfortable to drive between most places. It’s time to focus on the transportation and land use projects that grow similarly robust networks for other modes.

When choosing transportation investments — such as bike lanes, bus lines or a transit extension like BART to Silicon Valley — it makes sense to focus on how they improve the entire network. This is also known as the network effect. Linking transit-friendly destinations such as universities, cultural venues or downtowns — or effectively connecting transit with walking paths at those destinations — creates positive network effects. [3]

1. The Transit Network

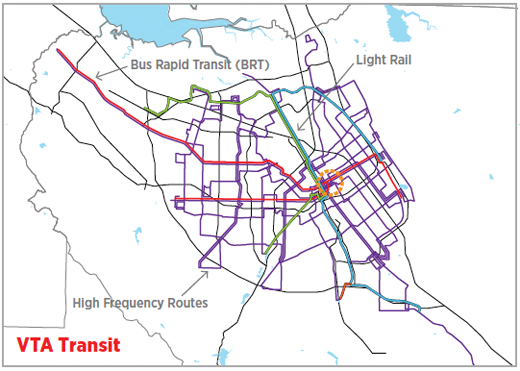

SPUR supports VTA transit projects that connect and are able to grow a high-frequency, reliable, all-day transit network. These include bus, light rail and shuttles or feeder buses. Today, there are 42 miles of light rail centered around downtown San Jose and close to 4,000 bus stops on 71 routes. 19 of those bus routes and all of the light rail lines have frequent all-day service (every 15 minutes or less). [4]

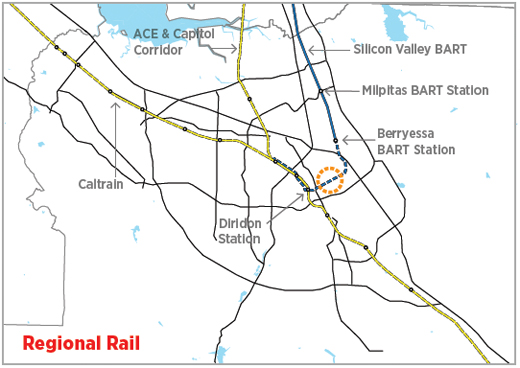

Big transit projects are underway: the first $2.3 billion extension of BART [5], to the Berryessa neighborhood in San Jose, is slated to start service in 2018, and further extending BART to San Jose and Santa Clara is in the planning phase. a bus rapid transit (BRT) route along Santa Clara Street and Alum Rock Avenue is under construction, and two more lines are planned for El Camino Real and Stevens Creek Boulevard.

Caltrain electrification is underway, as are major capital projects designed to speed up the light rail system. Making the transit network thrive will depend on making smart decisions about big capital investment decisions — and on getting the details right.

The big decisions include determining exactly where to extend the light rail or BART network or where cities should designate a lane for buses to operate at high speeds. The details include walking connections to transit, maps and signage, station design and giving transit vehicles priority at intersections. We also have to be strategic about operating funds: VTA’s policies support using limited bus and light rail operating funds on parts of the network that would benefit most from better service, as demonstrated by a local commitment to transportation choices or dense, mixed-use development.

There could be great value in better integrating existing VTA bus and light rail transit with the regional transit network, like Caltrain and, in the future, BART. For example, a shared fare structure between VTA transit and Caltrain could be created to discount trips using multiple operators.

The South Bay transit network won’t be complete without extensive or first-and last-mile transit to connect people in spread out communities with transit stations. Private and public shuttle buses, bikesharing and ridesharing are all great solutions. Effective partnerships with cities, transportation management associations (TMAs) and other parties are ways VTA transit resources and VTA’s expertise will make these connections happen.

2. The Bike Network

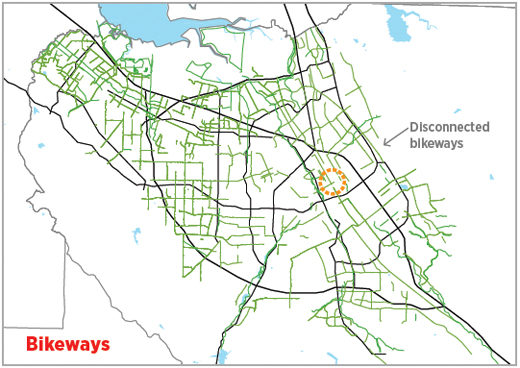

Most people agree that Santa Clara County is a great place for biking. Cities, the county and VTA have built many parts of a network: off-street trails like the Guadalupe River trail and the Los Gatos creek trail make for low-stress cycling, and buffered bike lanes have appeared in downtown San Jose. SPUR recommends growing the partnership between VTA, cities, civic groups like the Silicon Valley Bicycle Coalition and the private sector to invest in building a safe and easy-to-navigate bike network throughout the county. Striping bike lanes on roads or adding protective bollards are relatively cheap ways to build a network for bikes. Wide roadways found throughout the county can be retrofitted to accommodate transit infrastructure and bicycle lanes, as well as cars. To make biking a habit, more trails need to connect with city streets, to get cyclists all the way to their final destinations. Limited capital dollars can be focused on protected bike lanes, cycle tracks and gap closures that build the network out from key activity centers. There are many awkward crossings — arterials, expressways, highways — that have to be overcome one by one. Portland, Oregon, and New York City have experienced significant mode shift to bicycles by developing extensive bike networks.

3. Pedestrian Networks

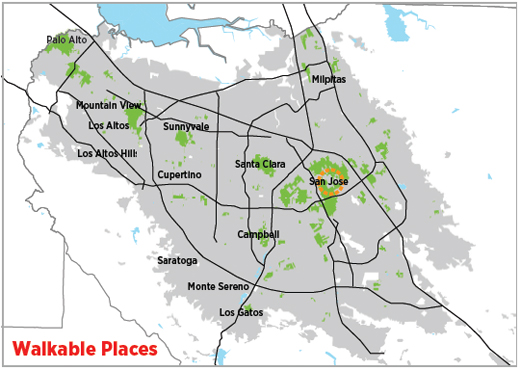

VTA funding and policies help create much-needed pedestrian networks. The prevalence of high-speed county expressways and arterials present major challenges to helping pedestrians feels safe [6]; the new bike/pedestrian facility alongside the San Tomas Expressway shows what a great network could look like. VTA’s Community Design for Transportation program, MTC’s One Bay Area Grant program and local general plans like San Jose’s Envision 2040 are all tools for retrofitting streets and land uses to make the walkable places that are crucial to transit’s success.

Paint is a low-cost approach to improvements. It can narrow car traffic lanes and add high-visibility crosswalks. Street lighting, speed humps, pedestrian signals or even speed limits can also complete a pedestrian network without significant financial investment. When it comes to the bigger pedestrian projects – bulb outs, medians, or pedestrian bridges — it makes sense to focus dollars on the parts of the network where there are the most people and most walkable land uses.

SANTA CLARA COUNTY TRANSPORTATION NETWORKS

The county has an expansive road network that connects with a network of parking facilities. Highways and expressways built over the last 50 years connect spread-out jobs and housing. The extensive Silicon Valley Express Lanes, among other projects, aims to make better use of this highway space.

VTA’s three light rail lines and 19 of its bus routes provide all-day service every 15 minutes or less. Projects are underway to enhance the network: One BRT route is under construction and two more are proposed. The Light Rail Efficiency Project would speed up service but more first- and last-mile solutions are needed to complete the transit network.

Caltrain, Amtrak’s Capitol Corridor and the Altamont Commuter Express provide rail transit access between the South Bay and the rest of the region. Billions of dollars are going toward bringing BART to Silicon Valley and electrifying Caltrain in the next few years. Connections between regional rail and VTA transit are not yet seamless.

The county’s terrain and weather are well suited for biking. Off-street bike paths, buffered bike lanes and regular painted lanes can be found throughout the county but are often unconnected and difficult to navigate. A focus is needed on new bike facilities and gap closures that build the bike network out from key activity centers.

Many parts of the county are well suited for walking, particularly in downtowns along historic rail lines. Missing sidewalks, high car traffic speeds, and long distances between destinations impede walking. Improving pedestrian networks across the county would also make using transit more attractive.

Source: SPUR analysis, Zack Dinh, Brian Stokle, and Brian Fulfrost & Associates

Networks Are the Key

Networks are what makes Silicon Valley tick; they’re also what makes transportation systems relevant. With each transportation investment, the transit, cycling and walking networks in the South Bay can become more useful and more appealing. Over the long run, planning the county’s transportation network and planning local placemaking together would prevent some of the ills of uncoordinated planning in the past.

SPUR’s Recommendations

SPUR’s report Freedom to Move: How the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority Can Create Better Transportation Choices in the South Bay includes 35 recommendations on how VTA can use all of the tools at its disposal to create great transportation choices. Selected recommendations for building great networks include:

Offer great bus service through corridors where there is a large transit market.

Several bus corridors see enough demand to warrant a significant upgrade to very high-frequency and high-amenity bus service, also known as bus rapid transit (BRT). SPUR believes that VTA BRT projects on these three corridors should adhere to high standards for BRT service — particularly, whenever possible, dedicated lanes for buses. New transit service delivery models can be developed for areas that are difficult to serve efficiently today.

Establish a Mobility Solutions and Innovation Team at VTA.

Growing the transit network into lowdensity areas will require creative solutions. A Mobility Solutions and Innovation Team would focus on both urban and suburban mobility solutions and would partner with other agencies as it scales existing mobility solutions and tests new ones. For example, this team could test a publicly supported ride-sharing program for suburban neighborhoods.

Retrofit streets for all users.

Through its role as a funding agency for local transportation projects, VTA can promote or require the design and retrofit of streets for all users, including pedestrians, cyclists and transit riders. VTA should also assist cities with adopting multi-modal street guidelines, sometimes referred to as “complete streets” guidelines. [7]

Read the full report at www.spur.org/VTA

References

[1] MTC/ABAG Plan Bay Area, 2013. Available at: http://www.onebayarea.org/plan-bay-area/final-plan-bayarea.html

[2] Dena Belzer and Shelley Poticha. 2009, “Understanding Transit-Oriented Development Lessons Learned 1999-2009” Center for Transit-Oriented Development. pp. 4-11 in Fostering Equtable and Sustainable Transit-Oriented Development. http://www.hud.gov/offices/cpd/about/conplan/pdf/Fostering_Equitable_an…

[3] Reconnecting America and the Center for Transit-Oriented Development 2009 Destinations Matter. Available at: http://www.reconnectingamerica.org/resource-center/books-and-reports/20…

[4] The frequent routes are limited bus service 522 and 323 and regular bus service- 22, 23, 25, 55, 57, 58, 60, 61, 62, 64, 66, 68, 70, 71, 73, 77, 81. Source: VTA Annual Transit Service Plan FY 2014-15.

[5] From http://www.vta.org/bart/faq#g

[6] Fast vehicles make the chances of a pedestrian being severely injured or killed significantly higher. At 20 mph, the risk of death to a person on foot struck by the driver of a vehicle is 6 percent. At 30 mph, that risk of death is three times greater. And at 45 mph, the risk of death is 65 percent — 11 times greater than at 20 mph. When struck by a car going 50 mph, pedestrian fatality rates are 75 percent and injury rates are more than 90 percent. From Dangerous by Design 2014, Smart Growth America. Available at: http://www.smartgrowthamerica.org/research/dangerous-by-design/dbd2014/…

[7] VTA defined these “multi-modal streets” in in its 2002 Community Design for Transportation manual. Other examples of multi-modal street guidelines include the Congress for New Urbanism — Institute for Transportation Engineers’ Designing Walkable Urban Thoroughfares: A Context Sensitive Approach (www.cnu.org/node/127) and the National Association of City Transportation Officials’ Urban Street Design Guide (http://nacto.org/usdg).