This article is the first in a two-part series about MTC’s Project Performance Assessment. The second post will focus on the Project Performance Assessment’s equity analysis.

Every four years, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) collects project proposals from Bay Area transit agencies and cities to assess their costs and benefits. MTC uses the findings from this and other inputs to determine which projects to include in Plan Bay Area and recommend for funding. That means the methodology used, called the Project Performance Assessment, has a lot of influence in determining which transportation project get built. The assessment, which models project costs and benefits in 2050 and assesses them across three very different scenarios of the future, is intended to add objectivity to the regional transportation planning process. This year, MTC made substantial improvements to the methodology. It now better considers equity and climate resilience and incorporates the lifetime costs of a project into the analysis. A total of 93 projects will be evaluated this time around, totaling more than $400 billion.

The draft results of the Project Performance Assessment are now in, and they offer a useful diagnostic for how project funding and planning in the Bay Area needs to change. We offer three key observations on what the findings mean for the region’s next generation of transportation investments.

1. There’s power in planning as a network rather than approving projects individually.

SPUR has long advocated for integrating the region’s many public transit services so they function like one rational, easy-to-use network. We have argued that if the Bay Area stops planning and managing each project and system independently, and instead plans as a seamless network, the region will make better planning and investment decisions for the future. Failing to plan as a network results in gaps in coverage in some places and duplication of services in others. Disparate fares make it more expensive for riders to make trips that cross multiple operators, and uncoordinated schedules result in long wait times that encourage travelers to choose driving over transit.

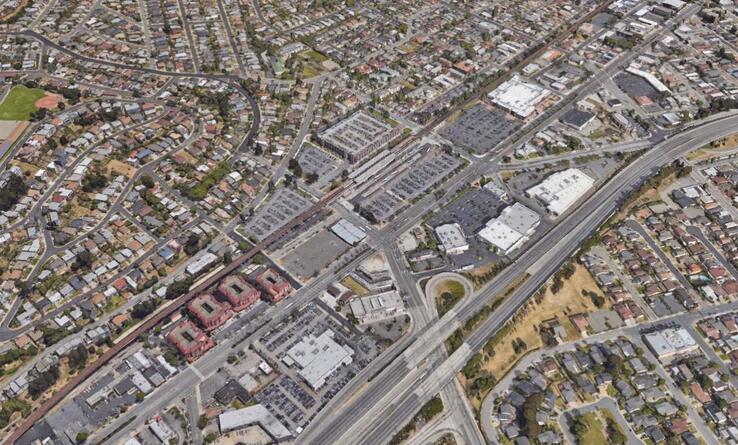

The Project Performance Assessment bears this out. The model shows that a planning process where each county seeks to maximize the investment in its communities doesn’t necessarily maximize the benefit to those communities — or the region. Instead, the results show that a suite of capital improvements designed as a network linking together multiple systems scores much better than most stand-alone projects, even if the cost to do them all is much greater. For example, individually, Caltrain’s long-range service vision, the project to extend Caltrain and high-speed rail to downtown San Francisco, the redevelopment of Diridon Station and a second transbay rail crossing for BART only do not score well in the benefit-cost assessment or across the three scenarios of the future. Yet coupled together in a network, with a second transbay crossing that incorporates both BART and other rail services, these projects have a positive return on investment. This should instruct how MTC and operators do their transit planning going forward.

2. The region needs to reform project selection and delivery.

The projects proposed to MTC this time around total more than $400 billion — far more than what the Bay Area can afford. To put this number in perspective, in the latest version of Plan Bay Area (Plan Bay Area 2040), MTC anticipated receiving $292 billion from a mix of federal, state, regional and local sources over two decades, but all except $60 billion of that must be spent according to federal and state formulas.

Not only will the region need more revenue, but MTC and the nine Bay Area counties — which generate more than half of the region’s transportation funding — will need to become far more selective about the projects that get funded. It becomes much easier to choose which of the 93 proposals to fund if project selection decisions are guided by a clear purpose and vision. SPUR supports a vision that builds a seamless, reliable, sustainable, equitable and cost-effective transportation network. At the core of this vision is a regional transit network that provides high-frequency service, maximizes connections between places, shortens travel times, shapes neighborhoods and supports regional economic growth. The vision should identify key corridors and routes and define minimum service levels and performance goals for each corridor — with land use expectations for growth around stations and stops. This service-based vision can guide investments in capital decisions, and it can help identify opportunities for policy changes, such as integrated fares, that create a more equitable transit system and improve connectivity without over-building capital projects.

Additionally, more accurate cost and benefit estimates will help MTC make better planning and investment decisions. Newly nominated ideas and projects, such as many listed in the Project Performance Assessment, are most likely to suffer from poor initial estimates of costs and benefits. This is because there are often few upfront resources for rigorous cost estimating in the early stages of a project. The Bay Area also needs to reduce project costs. Several long-planned, high-profile regional projects have poor benefits-cost ratios, in part because of their high price tags. At the same time, some of the more affordable projects, such as enhanced region-wide bike infrastructure, unsurprisingly provide a high level of benefits for the cost.

Bringing down project costs will require serious effort from the region and the state. History tells us that actual infrastructure costs — especially for large, complex megaprojects over $1 billion — are often much higher than their initial estimates. This is a global phenomenon, and common across all infrastructure sectors. It is especially true for transit projects in California, which tend to suffer from extreme institutional fragmentation as well as high land, housing and workforce costs, and an environmental review process that is often misused. All of these add delay and cost to new transit infrastructure, compromising progress toward our most pressing environmental and social goals.

Now is the time to begin improving project delivery to provide high-quality projects in less time and more cost effectively. Several large regional projects are currently being developed and designed. Now is the time to get them right, as it is this stage — and not the construction phase — where the biggest costs are baked in. Some of the most impactful changes MTC and others can advance include: implementing independent project oversight; strengthening the regional planning and selection process; evaluating project costs and benefits rigorously through business cases that account for major risks and overly optimistic assumptions; increasing the number of seasoned workers in fields such as project management and underground construction; and creating an entity that pools together expertise in procurement and project delivery and provides that support to multiple agencies.

3. The Bay Area needs to get better at using transit investments to shape growth.

Ridership is one of the strongest factors influencing a project’s benefits. High ridership reduces greenhouse gas emissions, vehicle miles traveled and a project’s cost recovery, among other indicators. Though the Project Performance Assessment does account for multiple scenarios of population and employment growth, the model does not account for project-specific land use changes, such as increased density near transit stations. Because the model does not assume that new transit will be co-located with new growth, it makes project benefits appear underwhelming: The “missing” growth translates to missing riders, missing revenue and increasing emissions. Additionally, some projects seem to perform well across a future scenario with high population growth but not in futures were there is moderate or low growth, reinforcing the fact that the right land use strategies could demonstrably change the equation.

Our next generation of transportation investments should be coupled with a serious commitment to growth around transit stations with high frequency service. Transportation projects are about more than mobility: They are urban development projects that have the potential to significantly shape neighborhoods, cities and the region. This is an area where the Bay Area has fallen short over the past four decades. For example, more than 75% of new employment growth has clustered near highway exits, not transit stops. Additionally, the Bay Area has not built enough affordable housing around stations in order to protect people with low incomes from displacement. New investments in transportation infrastructure should be matched by plans for lots more jobs and housing near stations — especially more permanently affordable homes. Otherwise, the Bay Area runs the risk of worsening the housing shortage and making it easier for people who earn high wages to live in lower-cost areas, which drives up housing prices. Ensuring a significant increase in the supply of both affordable and market-rate housing could help stabilize and even bring down housing prices, giving people with low incomes more options to choose from.

Conclusion

MTC has the difficult job of choosing which capital programs, projects and policies to advance — often based on imperfect information. One thing is clear: The Bay Area cannot afford a system made up of independent projects that do too little for too few. Planning as a network will help identify the most optimal projects and make sure they add up to deliver real value. Once projects are selected, addressing regulatory hurdles and implementing global best practices can help bring down project costs. And ensuring that transportation projects are leveraged to shape growth will help the Bay Area reach its goals for sustainability, equity and economic growth.