California is the world’s fifth largest economy, but the poverty rate is one of the highest in the nation: Almost 20% of the state’s children live in poverty.

This is also one of the most beautiful states, something voters have fought hard to protect for decades. But a car-based transportation system is thwarting our considerable efforts to curb greenhouse gases: Roughly 40% of California’s emissions are from transportation. We can see the pollution hanging over our heads as California is blanketed, county after county, in sprawl development.

Meanwhile, the state is projected to add 10 million more people over the next 30 years (reaching about 50 million). This means it’s about to get even harder to solve the problems that are threatening California’s well-being.

We need transformative change — the kind of big ideas that can address multiple issues at once.

Governor Newsom’s Region’s Rise Together initiative aims to address the growing disparities between California’s coastal and inland regions. The project’s team spent the summer convening leaders throughout the state to provide input into an action plan for a more inclusive, resilient and sustainable economy and better connections between California’s regions. SPUR believes that major new investments in passenger rail must be part of that action plan.

One of the major opportunities for California to stop sprawl, reduce emissions and strengthen regional economies — all at the same time — is to add new jobs and housing around passenger rail stations. With the next generation of transit investments focused on providing better, more frequent service, rail could become the backbone of transportation in the state. Growing around passenger rail stations would make it possible for more people to ditch their car for most trips, enabling a low-carbon life and reducing the cost of living.

In September, SPUR — together with GOBiz (the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development), the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, the California High-Speed Rail Authority, and the Council of Infill Builders — held a half-day workshop in Sacramento for staff members from California cities with passenger rail stations. SPUR asked: How can the state help cities spur compact growth and economic development around passenger rail stations for a more equitable, sustainable and prosperous California? What can we learn about this approach from each other and from international best practices?

Together, participants generated dozens of great ideas, captured in this graphic illustration, which took up an entire 16-foot wall. Presentations from the workshop can be downloaded here.

Three Challenges

SPUR is a big believer in learning from other cities and applying international best practices (and cautionary tales) locally. But in California, it can be very difficult to transplant best practices because existing laws, policies and practices simply don’t allow them to be implemented. At times, even the most ambitious cities in the state end up locked into business as usual. Here are three of the biggest flaws that make it difficult for California’s cities to grow around rail. These issues explain why transportation investments of all kinds have led to sprawl:

Issue 1: The state’s transportation investments are not tied to a geographic and economic vision for California’s growth. California plans and manages transportation and land use independently, at all levels of government. But as panelists discussed, other countries do it differently; investments in transportation are about more than mobility — they are intended to grow and connect local and regional economies. For example, in the Netherlands, the national government produces a high-level growth strategy for all regions in the country. In planning to connect to the European high-speed rail network, the national government produced a plan that selected six stations in the Randstadt region as “key projects” for modernization and redevelopment and made a financial commitment to each of them. This initiative originated in the Ministry for Spatial Development, not the Ministry of Transport. To make the most of California’s transportation investment, it should be part of a package of actions that shape growth around stations.

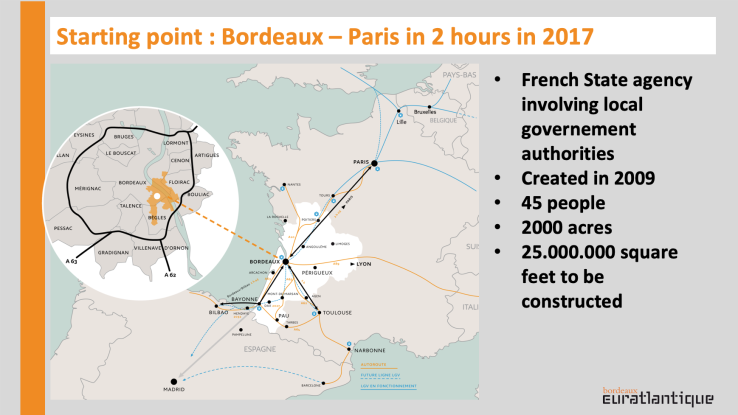

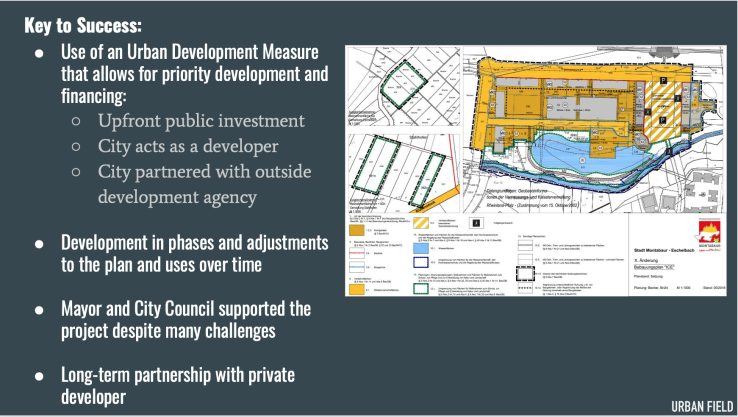

Issue 2: Cities do not automatically have the tools and expertise to do major urban redevelopment projects around stations. Most successful station area redevelopment efforts in other countries start with an initial “big move” or commitment from the public sector, such as putting a highway underground, preparing parcels of land for redevelopment or locating government offices next to the station. This is especially true in mid-sized and small cities, where the private sector’s willingness to invest in infrastructure or locate near stations is more limited and the market is unlikely to support more compact growth around stations. In Germany, major infrastructure projects can get access to the state’s urban development measure, a tool that essentially allows cities to act as developers in order to implement very large projects that will meet public interests. Projects qualify for the tools if they build significant new public goods (such as a rail station), increase jobs or create new neighborhoods. Similarly, in France, projects that are designated as having regional or statewide significance are allowed to create publicly owned special purpose entities that have a deep bench of cross-disciplinary expertise in urban development, as well as tools such as upfront financing and the ability to buy and sell land. This helps to overcome market barriers and makes it possible to build a great station and new neighborhoods around it.

Issue 3: It is difficult to concentrate growth around transit stations until the transit is running. Many of the city staffers at the workshop felt that the time it takes to get rail and transit funded and built was also a barrier, because the long timeframe creates uncertainty for developers. Additionally, station cities from inland areas expressed concern about the stability and availability of funding for transit — both capital and operations — because they don’t have the base to sustain sales tax increases to fund public transportation.

Reforming How California Plans for Growth

California’s greenhouse gas emissions and sprawl problems were decades in the making — a product of our transportation and land use decisions — so there's no silver bullet solution. Here are just a few of the creative and bold ideas that participants in the workshop articulated throughout the day that can help ensure that rail shapes growth for good:

1. Create a stronger role for the state in shaping land use around rail stations. There is already a lot of transit without development — stations surrounded by parking lots, where the zoning hasn’t changed to allow for higher densities or a mix of uses. California will not be able to see the full benefit of its investment in rail without playing a role in shaping growth.

- Make state transportation funding contingent on the establishment of growth controls. Transportation funding — both for rail and for highways and roads — should be contingent upon cities and counties having growth controls such as urban growth boundaries. Such tools work to preserve open space and combat sprawl in cities and counties. The demand for new roads is higher than the demand for transit in many places, and it is well-established that new highways and roads induce sprawl, so this requirement should extend to car-oriented transportation dollars (at least the funds that are not constitutionally protected).

- Acquire and bank land for the public purposes of economic development, affordable housing or transportation infrastructure in station areas. The state could purchase land directly or provide funding to cities and rail agencies to purchase parcels close to stations. International best practices show that successful station area revitalization depends on the ability of the public sector to acquire, hold, sell and lease land. Many cities will need financial assistance to purchase the land because they lack the necessary flexibility in their budgets. Once in public ownership, long-term leases can be used for the public purposes of spurring economic development and providing affordable housing.

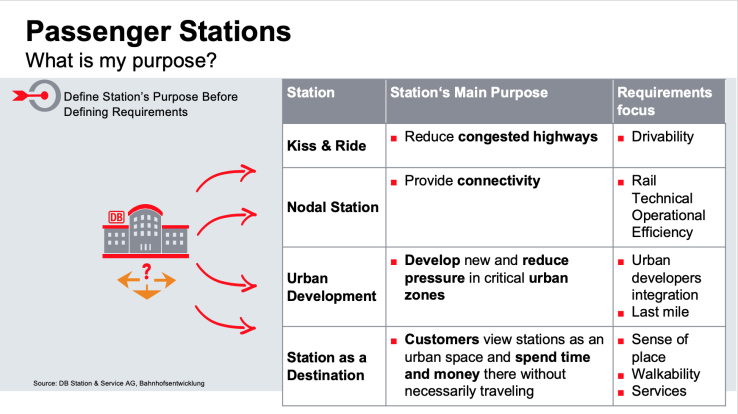

- Define the purpose of each station. The stations in the statewide network are located in different types of places and will serve different functions. For those in the largest cities, the station is a destination and an anchor of public life in its own right. These are the places that should have the largest concentrations of employment around them and draw on a regional or megaregional labor market. They are also the places where all modes of transit — commuter rail, metro rail, regional express buses, local buses and streetcars — should converge and have the greatest frequencies. Other countries create a typology of stations that defines their purpose, then use it to guide planning and funding decisions about transit frequency and transit-oriented development.

Source: Jorge Rios, Vice President of Business Development, DeutscheBahn Engineering

2. Give cities the ability to do urban development around stations. Major rail projects should not be projects of regional or statewide significance in name only. In other countries, rail projects are city-building projects, and cities with rail projects can access a suite of tools to promote urban development for a set period of time. The key tools necessary include the ability to acquire, hold, sell and lease land for development, getting upfront funding (for example through a revolving loan or the sale of land) and the ability to finance and construct new buildings (through value capture tools). In countries such as France and Germany, this work is centralized into a small, nimble organization that works on behalf of the public or is publicly owned. The group has a significant breadth of in-house expertise, including real-estate deal-making, procurement, risk management, construction project management, architecture, law and planning.

Source: Eric Eidlin, Station Planning Manager and German Marshall Fund Cities Fellow

Source: Heidi Sokolowsky, Partner, Urban Field Studio

3. Expand funding for transit and transit operations. In recent years, California has created several new sources of transportation dollars, but the magnitude of need is still great. City staffers expressed a need to fund and deliver transit projects faster and to provide higher quality service (such as more frequent trains and buses). They recommended several reforms to state funding mechanisms, including:

- Extend the cap-and-trade program past 2030. In 2017, legislators voted to extend California’s cap-and-trade program, which provides a critical source of funding for several transportation funding streams. The extension is to 2030; pushing it further would give greater financial assurance for rail and station projects that are currently in the planning stage and have not yet secured full funding, including but not limited to high-speed rail.

- Toll state-owned highways. Tolling state highways would create a new source of revenue for public transportation, particularly operating dollars. It could get transit projects funded faster and make transit more competitive with driving, helping to give people more transportation choices. This could help increase transit ridership, which would boost revenues and reduce the amount of money required to subsidize transit operation.

- Expand the Transit and Intercity Rail Program, and separate it into two programs: one focused on rail and one focused on local transit. Non-commute trips and short trips make up the biggest share of total trips in the state, and many of them could be shifted from cars to local transit. Additionally, it is not cost-effective or practical to extend rail everywhere. The rail network will need to be supplemented with affordable, high-frequency, high-quality local transit and express buses for shorter trips and to extend access to the rail network. California’s Transit and Intercity Rail Program uses cap-and-trade revenue for transformative capital improvements. Expanding it will create more revenue to build and operate transit and rail projects, and breaking it into two programs will ensure that these types of projects don’t compete against each other, as both are critical to solving our climate crisis.

- Reform the Transportation Development Act. This 1971 law allocates funding from state sales and gas taxes to transit agencies. To receive funds, transit agencies must meet a minimum farebox recovery (the percentage of operations that are covered by revenue from fares). In rural areas and other places where ridership is low, this requirement can create a downward spiral: Less service makes transit less useful, suppresses latent demand and continues the cycle of car-dependence, making it difficult to grow in a more compact and transit-friendly way. A legislative task force has already been convened on this issue and is a good step toward creating new metrics to determine how to allocate funding.

Creating great cities anchored and connected by rail will require more than forward-thinking local leadership and good urban design. The State of California will need to fix some of the fatal flaws in how it plans for transportation and land use.