As urbanists, we talk a lot about the importance of walkability — but maybe not enough about the pleasures it can bring. Last year, we invited San Francisco walkers to muse on the subject. This issue, we extend the invitation to Oaklanders. Their stories are below.

1 | On Broadway

For the last decade, I have walked on Broadway every day. This is where Oakland feels like a big city. From the people pouring out of the BART stations, getting sworn in as citizens at the Paramount Theater, walking from one place to another or just waiting for the bus, this is Oakland’s main street. Broadway is the most iconic street in Oakland, and I think also the most interesting.

In recent decades, it hasn’t always been that way. Broadway was infamously dug up in the late 1960s and early 1970s for the construction of the BART tunnel, and that tore the heart out of the street. I have heard much about the glory years before BART construction and before the department stores moved away. By the time I got to Oakland 20 years ago, Broadway had waned, but it is really on its way back now.

Photo by Robert Ogilvie

Photo by Robert Ogilvie

When I have to get somewhere I usually take a different route coming and going, because that way I can see twice as much as I would otherwise. With Broadway it is a different story. There are so many different types of people and there is so much renovation and new building going on that you can come and go on same stretch of Broadway and from one minute to another you will see something different. Lots of people have written songs about Broadway — okay maybe they were about a different Broadway — but still I hum them as I’m walking. In the evenings after work, when the marquee at the Paramount is lit, I hum George Benson, but during the day it’s usually James Taylor because this is the place for “watching the people, watching the town go down.”

Robert Ogilvie is SPUR's Oakland Director.

2 | The Jewel of Oakland

In a world where walks double as exercise and as therapeutic stress relievers, I cherish my favorite walk in Oakland. Walking the 3.4-mile Lake Merritt shoreline in downtown Oakland is truly one of my favorite things to do. Known lovingly as Oakland’s “living room,” the 155-acre lake (the largest body of salt water within city limits in the nation) represents everything that is wonderful about the City of Oakland. The rich cultural diversity, friends strolling, others running, people of all ages enliven the living room everyday. My real favorites are the weekends when I walk from my house to the lake and witness the myriad of activity around the lake that represents why cities are so desirable. There will be a group of people who have a slack wire tied between two trees balancing on the wire and juggling. You’ll walk another mile and witness friends dancing the best salsa and tango you have ever seen. While your lungs are filling with fresh air and the sunshine is hitting your face, as it often does in Oakland, Lake Merritt really does invite you to enjoy it. It’s a gift to al residents and visitors alike.

Tomiquia Moss is Chief of Staff for Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf.

Photo by Sergio Ruiz

Photo by Sergio Ruiz

3 | Poem for Ann Hood

On my walk today

I heard behind

a wooden fence

someone sweeping

and thought on some

certain day I too

will have lived

long enough

to know the names

of what here

in northern California

they call the seasons,

which music

makes the house

exactly happy

for no guests,

and how to wait

for a call from a far

off happy child.

I looked up at three

crimson apples

from a single

high branch hung,

past them blue

endless steps

upward toward

whatever moved,

and to my beloved

morning glory

so purple at my feet

in Oakland everywhere

I said weed

that is a flower,

please tell me

can one grow

an orange bird

of paradise

in zone 9

so I can inform

my wife who loves

to place in the garden

what has a chance

to live with

more than a little

water and care.

It could not say.

Then in my mind

at last I thanked

you for the various

violet spectral

shades you so sweetly

joined to cover

the small new body

we wait to know.

All the while

you were knitting

you were surely

talking laughing

and as always thinking

also of something else,

and all became

amethyst midnight

wisteria nocturne

sound of jewels

and mourning

emperors to warm

ourselves beneath,

a little sad

and peaceful to know

I might not ever

know what time

is but you and I

have always been

sure it is nothing

like the carefully

draped resolved

or endlessly waiting

time in a book to which

we can always return.

Matthew Zapruder is the author of four collections of poetry, most recently Come On All You Ghosts (Copper Canyon 2010), a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. He lives in Oakland.

4 | Eat Your Weedies!

Tom and I race from the Berkeley campus to BART just before noon, eager to get to “the field.” We exit at West Oakland and head north on Center, past the Check Cashing, Donuts & Burgers, and Convenience Store building, with its tin roof and black-and-white jazz mural. The sidewalk is peppered with fast food litter. It’s also peppered with fresh food: wild edible plants grow through cracks and in every patch of dirt (shown above). These city streets are an ecosystem, and that’s why we’re here. We’re headed to 14th and Peralta, but the abundance and variety of edible plants on the way distracts us.

We’ve been here repeatedly to map plant abundance, collect soil to test for lead and other metals, and collect plants to test for toxics and nutrition. Despite the record drought, there are hundreds or thousands of servings of fresh greens per block, even at the end of the summer.

Our study zone is a three-block-by-three-block area the USDA calls an urban “food desert” — a low-income area far from any grocery store — but we know from past visits that the area is anything but a desert: It’s a garden of nutrient-dense wild edibles, fresh and free. As we approach, we feel like kids entering a candy store. What will be ripe, robust, and plentiful this week? Sweet fennel? Bristly ox tongue? Nasturtium? Dock? Dandelion? Cat’s ear? Plantago? Wild radish? Mustard?

Tom Carlson, my co-investigator, is a professional — an ethnobotanist and practicing pediatrician. I’m a self-taught amateur. We probably look out of place — two white, middle-aged guys in a predominantly African–American neighborhood — but we are in our element, as all humans are while foraging. We are distracted by anything green: Where others see nondescript weeds, we see a forest of delicious, nutritious, carbon-neutral, drought-tolerant, fresh, free food.

In urban food deserts, where diet-related chronic diseases are disproportionately prevalent, the nutritional potential is especially compelling. Of course, harvesting from the sidewalk won’t solve food insecurity. It’s not a substitute for grocery stores. And it won’t eradicate health inequities. But noticing and harvesting the wild foods that volunteer at our feet has great value. It can feed us fresh, tasty, and nutritious greens, as diverse and interesting as Oakland itself. It empowers us to do something about our own nutrition and reminds us that nature is everywhere.

Philip B. Stark is a Professor of Statistics at the University of California, Berkeley and a self-described botanical rubbernecker.

5 | Cleveland Heights and "Borax" Smith

With Gene Anderson of Our Oakland, you can spend your Saturday exploring all sorts of Oakland neighborhoods. Below, a recap of his recent tour of Cleveland Heights and the nearby former estate of F. M. “Borax” Smith. An Oakland businessman and civic leader who made his fortune in borax, Smith is best known in Oakland for his contributions to civic infrastructure, including his efforts to consolidate a water company which eventually led to the East Bay Municipal Utility District.

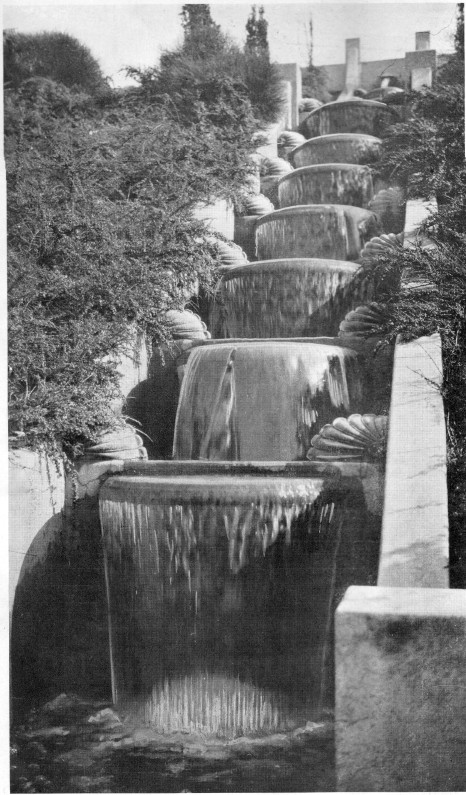

We start the walk at the Cleveland Cascade near Lake Merritt, designed by landscape architect Howard Gilkey and built in 1923. It was likely shut down during World War II, but was reactivated after the war. At some point the cascade was turned off, fell into disrepair, and became overgrown and full of trash. In 2004, a group of neighborhood volunteers uncovered and cleaned up the cascade and have since put in new railings and lighting; they’re now trying to get the water flowing again.

From there we meander across Cleveland Heights, keeping an eye out for gnomes, sidewalk stamps, murals and other surprises. We eventually cross over Park Boulevard into the Ivy Hill neighborhood to Arbor Villa, which was once the estate of “Borax” Smith. While the 42-room Oak Hall, gardens, out buildings and observation tower are all gone now, a row of palm trees marks one edge of what was once the estate. (Seeing an old palm tree in Oakland is often a good sign that someone notable lived nearby, but the Arbor Villa palm trees are the best example.)

We then make our way back across Park Boulevard toward some buildings that are left from the Mary R. Smith Home for Friendless Girls. Smith’s first wife, Mollie was inspired by Benjamin Farjeon’s book, Blade O’ Grass about orphans in London, and started this orphanage for girls. One of the “cottages” includes an impressive structure at 3001 Park Blvd., designed by noted architect Julia Morgan. Our route back to the Cleveland Cascade takes us past a home once owned by industrialist Henry J. Kaiser and down some beautiful stairs to Beacon Street.

Gene Anderson leads (and blogs about) walking tours of the city of Oakland. Learn more at ouroakland.net

6 | The Lake Saved My Life

Lake Merritt saved my sanity. It was a summer of crisis for me; my relationship had dissolved, I was ejected from the home I shared with my partner and my employment situation was unreliable. I was in a tailspin. I sublet an apartment a couple blocks from Lake Merritt while I got my bearings. Each morning, I would spring out of bed and head for the lake, where walking the loop proved to be a form of moving therapy. You would think doing the same walk day after day would be boring, but each day was unique. Often the cormorants would be slinking and darting around just beneath the surface, or there were pelicans swimming in tight groups filling their bag-like necks with water. By mile three of my walk, the anxiety always sloughed off and it seemed that things were going to be okay again.

Photo by Sergio Ruiz

Photo by Sergio Ruiz

Rebecca Pollon, a board member of Walk Oakland Bike Oakland, is a landscape designer in the East Bay.

7 | The View From Millionaire's Row

Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland combines several of my favorite activities into one location. It’s the perfect mix of history, architecture, nature, great people watching and a nice walk. It helps me convince people skeptical of visiting a cemetery that this is an amazing place.

First some history. If you lived in San Francisco in the late 1800s and were very rich, you wanted to be buried in Oakland. You may have noticed that aside from the Presidio, Mission Dolores and the Columbarium off Geary, there aren’t any cemeteries within the city limits. This is due to a city ordinance that had them all moved to Colma after 1900, leaving very few places to be buried in San Francisco itself.

One solution to this problem sits at the end of Piedmont Avenue in Oakland: Mountain View Cemetery. It’s a 226-acre Victorian garden cemetery crafted by Frederic Law Olmstead, who designed New York City’s Central Park. And if being designed by the world’s most famous landscape architect wasn’t enough, it also has some of the most amazing views in all of the Bay Area. This was an important quality, because if you were one of the founders of say, a railroad, you wanted your monument to be seen all the way across the bay by your family (and neighbors) back on Nob Hill in San Francisco.

Photo by John Cary

Photo by John Cary

Locals treat Mountain View like a monument-filled Golden Gate Park. One hot day while walking my dog I came across half a dozen people having an opulent picnic while dressed like members of Louis XIV’s court. I was so surprised I forgot to ask them how such a thing came about. As you wander around, you will see the nameas of local landmarks, streets and cities: Haight, Crocker (the one who could see his monument from his house on Nob Hill), Stanyan, Merritt, Tilden, Chabot, Colton. You will also notice the names of local businesses, like Folger, Bechtel and Ghirardelli.

The cemetery’s main office will give you a map of all the highlights so you can wander around on your own. But there are also great docent tours on the second and fourth Saturdays of the month. I’d recommend picking up lunch somewhere on Piedmont Avenue and taking a break from your walk at one of the grand mausoleums on Millionaire’s Row. The views of San Francisco and downtown Oakland are amazing and you might just be able to see your house.

Alanna Cloutier is an Oakland-based writer.

8 | Oakland's Urban Gateway to the Redwoods and Beyond

In 2007, after opening a new location of La Farine Bakery in Oakland’s Dimond District, I moved into the neighborhood. With I-580, a major AC Transit bus transfer hub, and an easy connection to BART just a block away, I quickly learned how accessible my new community was. But soon, I realized even grander access – Oakland’s Dimond neighborhood connects through parkland to the Bay Area Ridge Trail and over 500 miles of trails that span the entire East Bay.

Tucked between the Dimond, Glenview, and Oakmore neighborhoods, Dimond Parkfeatures 14 acres of urban park including playgrounds, picnic areas, grassy fields, tennis courts, a swimming pool and recreation center. Its paved paths wind through the park amenities, along Sausal Creek, and through towering redwoods and majestic oaks. At the top of the park, crossing sleepy El Centro Ave, you’ll enter Dimond Canyon Park, home to ninety acres of gorgeous wild land park and trails. Dimond Canyon, Old Cañon, and Bridgeview Trails connect and wind through the oak, laurel, and redwood forests along Sausal Creek. At the top, almost two miles from Dimond Park, you’ll reach Monterey Blvd, where a pedestrian tunnel under Highway 13 invites you to enter Joaquin Miller Park.

Photo by Stan Dodson

Photo by Stan Dodson

At the Palos Colorados trailhead, the lowest entrance to Joaquin Miller Park, you’ll experience one of the Bay Area’s most beautiful trails. The thick tree canopy and year-round creek will make you soon forget you’re in the middle of a city. While some areas of Joaquin Miller Park are developed, it’s home to a Ranger Station, Community Center, picnic areas, fenced dog runs, and the historic Woodminster Theater, most of it is natural and wooded, with an exceptionally well-maintained trail system, thanks to collaborations between the City of Oakland and volunteers. You’ll find redwood groves, chaparral, year-round streams, and expansive views of the entire Bay Area.

Crossing Oakland’s Skyline Boulevard at more than 1,500 feet elevation and almost five miles from Dimond Park, you’ll reach Redwood Regional Park and the Bay Area Ridge Trail. You now once again have many options: take the 339 bus line from Chabot Space & Science Center (just a ten-minute ride) back to Dimond, loop around for a round-trip hike of nine miles that will bring you back down the hill, or keep going towards Tilden Park, Moraga, San Ramon, or Hayward … the list goes on.

This urban connection to the East Bay’s vast network of parks, trails, and open space is incredible. You could hike for days and days, and never touch the same piece of ground twice.

Stan Dodson has worked as a volunteer to promote and maintain Oakland’s wildland trails since 2008. Learn more at OaklandTrails.org