Dean Macris, returning for the third time as San Francisco’s planning director, wants architects to know that if they bring good design to the department, they’ll get its support — instead of a stultifying and unending process. He tells Gabriel Metcalf that he’s repositioning a newly energized department to run like a business and is collaborating with AIA SF to instill a new way of thinking about architecture in the city. Macris is well north of retirement age, but he talks about change with a sure sense of direction and purpose. And enthusiasm. Oh, and did we mention the depth? This man is the walking, talking primer on urban planning history in San Francisco.

Gabriel Metcalf: Dean, let’s start with your career path. How did you end up here?

Dean Macris: Well, it was a long time ago. … I graduated from planning school at the University of Illinois in 1958. I then spent 10 years in Chicago and ended up as an assistant commissioner of planning, third-ranking person in the planning department. In those days, the heavy demand for planners was promoted in great part because of the federal government. To qualify for federal funds aimed at redevelopment and renewal, cities had to document that a sufficient number of professional planners were available. It was a wonderful time for young planners.

Meanwhile, in the mid-1960s in San Francisco, SPUR was agitating for planning reform. Arthur D. Little, a planning consulting firm, was contracted to do a citywide renewal plan, and the Chamber of Commerce was the principal factor in downtown planning. The Planning Department was not in the mainstream.

Allan Jacobs was hired as the director of planning in 1967. After a visit here and a heavy dose of persuasion from my wife, I joined the San Francisco Planning Department in June 1968 as assistant director. …

When Allan decided to leave the city and teach at Berkeley, Mayor Joseph Alioto asked if I would finish [Jacobs’] term as director, and I did for about a year or so. After George Moscone was elected mayor in 1975, [the Association of Bay Area Governments] asked me to join them to do an environmental management plan for the region.

But after the tragedy of Mayor Moscone’s assassination, Mayor Dianne Feinstein called and asked if I would come back to the city. I agreed to do that in 1980. So until 1992, I was the planning director under Mayors Feinstein and Art Agnos. When Frank Jordan became mayor, I retired from city government. I went to work on various projects of interest where I thought project sponsors would find me useful. One rewarding project for me was working with the Giants to build a new ballpark on a site I had advocated for many years.

In November of 2004, Mayor [Gavin] Newsom called, telling me the city hadn’t found a director, and the Planning Department was in need of some immediate help. He asked if I would come back for a few months. My affection for the department hadn't changed. So I agreed to do it, even though I'm well over retirement age. I've been here ever since, and I think we've made a lot of progress in restoring the department’s reputation and effectiveness.

Metcalf: During your previous stints as planning director, what were the major things you got done? What are you most proud of when you look back?

Macris: The decade of the 1980s was probably the most productive 10 years this department ever had. We published the downtown plan, which I think still stands as one of the paramount documents of the profession. That plan introduced so many ideas that were enacted in the city’s planning code. …

The amazing thing is we couldn’t get the money that we needed for some consultant help. So the downtown plan was drafted, essentially, by our staff. We had an outstanding blend of skills at that time. My contribution was to get the right people to do the things they're best at doing and then figure out a strategy to make it happen. In terms of land use organization, scale and services, and pedestrian interest, all of it walkable, I believe we presently have one of the best central districts in the country, if not the world.

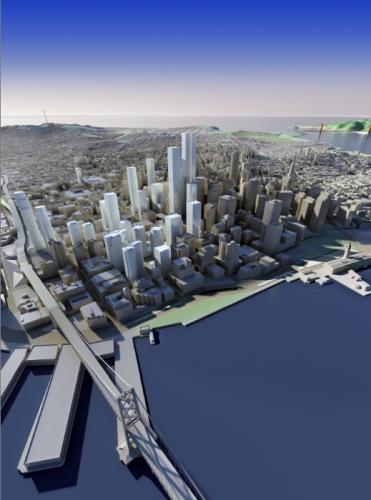

With long-term prospects for a vibrant economy and new leadership by the city, significant urban infill is happening in the Transbay and Rincon Hill neighborhoods — just where the Downtown Plan and Rincon Hill Plan called for growth. Image courtesy Skidmore, Owings & Merrill Urban Research.

A second thing I should mention is that we rezoned all the 240 neighborhood commercial districts in the city in the 1980s. Completely changed the code for all of those areas. We have very defined districts with limited space, fine for walking, and compactness, but it also makes those commercial districts on the high-rent side. So one big issue was how to protect local services. Restaurants and banking institutions could pay higher rents, but it was tough for shoe repair, drycleaners, hardware stores. We attempted to create rules to limit banks, restaurants and drinking establishments to make room for other services.

A third accomplishment from that era was all the rezoning around downtown to prevent the downtown spillover into adjacent neighborhoods. We rezoned the Tenderloin, parts of North Beach, and the South of Market area to maintain a mix in uses and building scale.

Finally, the department very successfully planned and rezoned Rincon Hill and Van Ness Avenue to create the potential for new housing. That was quite an accomplishment, and housing construction at both those locations is still underway. …

Metcalf: In your third run as planning director, what are the major things you’re trying to get done?

Macris: I have a good sense about how difficult it is to reach consensus around a vision for the city. If we got 50 San Franciscans of various points of view into a room, I'm not sure we could ever arrive at a common vision. But there are certain planning needs and directions I believe can be accommodated for a better city.

One, we have to sort out the optimum land-use changes in our traditional industrial districts. That’s obviously high on the agenda, and the department has been working on this issue for years without a successful conclusion. It’s not just us: Every major city is in the process of rethinking districts that represent the manufacturing past.

We also need to finish the [environmental impact report] for what we call the Eastern Neighborhoods by the end of this year, make our recommendations, and have a sensible debate at the Planning Commission as a first step toward new zoning rules for this part of the city.

Those districts very much represent the city’s future. But we also have to create a new place for downtown to grow. In addition, we are establishing a preservation survey program for the entire city so we understand our historic and architectural resources more clearly. Beyond that, we have to find a way for affordable housing developers to afford land so they can build. Is there a tougher question in a dense, built-up city like San Francisco?

Historic preservation, adaptive re-use, and foot access all combine in the rebuilding of Pier 1 as offices for the Port of San Francisco and rental office space.

Pier 36 and much of the southern waterfront languishes while the Port and private developers try to find economic uses that will fund decades of deferred maintenance. Above photos by Lori Armstrong-Mathieu.

Metcalf: This problem has bedeviled our profession from the beginning. The founding text of city planning, Garden Cities of Tomorrow [Ebenezer Howard, 1898], is essentially a big plan for a community land trust intended to solve the so-called “land problem.”

Macris: It is the toughest one, no question about that. But the problem is not unlike stabilizing a spot on Chestnut Street for shoe repair, which was the thrust of our retail diversity efforts in the 1980s. It’s the same kind of planning issue.

We also need to find a way to allow an urban waterfront to get created. We’ve got too many rules governing the waterfront. This is not a criticism of the agencies involved. They were established at a time when there needed to be safeguards, but now the City and the public have a very good understanding of what should and should not be on the waterfront. There are some good ideas about what makes a great urban waterfront. But we’re stymied by the rules. Even the Giants ballpark was tough to get. It took every ounce of lobbying. How could it not be a good idea to bring 40,000 people, 81 times a year, to the waterfront to enjoy the views and walk along the waterfront? We had to overcome the opposition — not from the public, but the rules.

Metcalf: And now we’re watching the piers rot into the water because we’re not allowed to convert them to modern uses.

Macris: Exactly. Look at the great waterfronts in the world. We don’t have Chicago’s climate, and we’re not going to have sand beaches on our waterfront. But, boy, could we have a great waterfront and still keep references of the past. The piers could be used in different ways. Goodness, we could even have some housing on the waterfront as long as we protect public access.

Metcalf: You were brought in as a reformer with the job of restoring the public’s trust and elected officials' trust in the department's basic competency to get work done in a timely manner. How have you approached that?

Macris: That has a lot of facets to it, but I'll go over them quickly. We did some things just to upgrade the basics of the department. One was to begin a program to revamp our computer system to integrate information with the department of building inspection. We wanted to completely revamp a chaotic fee schedule that lost its rationale over the years. We did that. We now have a management consulting firm looking at the way we do business. We expect the results of that report soon. We’re going to physically move the department to a new location and to consolidate our two offices. I think this will have a great psychological benefit, because if we work in a space that looks like business, we’re going to behave like we mean business.

Most important, we made dozens of staff changes and brought on new people —32 percent of our staff is comprised of new people. The department’s total has reached near 150. Now our staff resources more accurately reflect the amount of work we’re asked to do. We have this young, energetic staff, lots of enthusiasm. We must also focus on managing ourselves better. Planners don’t come from a tradition of management, but we plan to work on this in the coming months. …

Metcalf: Dean, one thing I know you care a lot about is the quality of building design. This is always a tough issue because, as planners, we don’t want to pretend to be the architects. We can’t be overly restrictive. But the balance between good urbanism and good architecture is hard to find. What do you think is the right way to approach this?

Macris: We need to instill a new way of thinking about architecture in the city. We’ve gotten stale. In the 1980s, there was the charge that the downtown plan was too stifling architecturally. But it’s more than that. We don’t have a culture of innovation in architecture. We’ve really never had it. It’s not the downtown plan. There are some fine early 20th-century buildings downtown and a few from the last 20 years or so. Residentially, we have our unique way of doing things because of traditional-style residential districts. But in our bigger buildings, like other cities, we sort of lost an urban design sense after World War II.

Planning is in no position to tell an architect who shows us a homely design for a big building, “OK, we’re going to make you a good architect.” But as a department, we can create an environment in which good architecture can happen. …

To help change attitudes and what our standards of design ought to be, we have engaged the local [American Institute of Architects] chapter in making presentations about such matters as innovation, context and so forth. Incidentally, we’re pleased that the new cluster of buildings across the street from the Transbay Terminal will include a design by Renzo Piano. It’s another way to help bring attention to the importance of architecture.

People wonder about Chicago, speaking of good architecture. Not that every building in Chicago is great, but lots are. It’s not because the planning department there won’t accept anything else. It’s because there is a tradition, and the builders themselves know they’ve got to compete against other buildings. In downtown Chicago, with thousands of units on the market, a builder knows that one way to compete is with better architecture.

Metcalf: Some architects will tell you they have been forced to dumb down their work to the lowest common denominator to get through the gauntlet of the approval process. Do you think there's truth in that?

Macris: Do I believe there’s talk that goes something like this? “Well, don’t go into the Planning Department with something that looks too out of context, too cutting-edge, because they’ll reject it. You’ve got to have a middle-of-the-road building that has context in order to make planners happy.” Do I believe that happens? Yes, I do. What we are trying to say is, “That's not the way to succeed here anymore.” …

Metcalf: If you imagine San Francisco 10 or 20 years from now, what would you most hope might be different about the city?

Macris: Ten or 20 years is not a long time in a city’s life. But I think it’s pretty clear that what will bring new life and vitality to cities are the emerging mixed-use neighborhoods. Proximity to jobs, services, educational, entertainment and cultural resources is becoming attractive to an increasing number of people. For many people, but not all, urban life is looking pretty good compared to other living choices in the region.

San Francisco needs to find ways to keep these neighborhoods balanced, diverse and pedestrian-oriented, to make them flourish and grow in attractiveness over time. The City will need to invest much more in these districts in the appearance of streets and the public realm in general. Recognizing all of this, we have started to shape a better streets program. The idea is to create, say, a 10-year program for improving streets — the way they are used, look and feel.

In my mind, all these planning efforts we discussed today fit together: diverse, mixed neighborhoods; attention to affordable housing; major improvements to the public realm; retaining traditional San Francisco through intelligent decisions about preservation; room for downtown to grow. And how about some innovation on the waterfront?

This article has been adapted from an interview previously published in LINE, the quarterly design journal of AIA San Francisco. Reprinted with permission.