The map on the opening page of a glossy new book on New York’s “Percent for Art” program makes an eloquent point: publicly funded public art mostly goes where development energy in a city goes. Transit, open space, and other improvements that generate percent-for-art dollars radiate from downtown to strategic outlying areas—more often than not where new residential and commercial development is slated. Aside from the downtown, these new or newly “revitalized” neighborhoods tend to be richest in public art projects. And so on.

Portland can plot its own development-driven map: the MAX Blue Line is a veritable museum of public art, whisking the rider from Pioneer Courthouse Square to the transit-oriented communities of Beaverton Creek, Orenco, and Hillsboro. “Fareless Square,” the recently refurbished pedestrian-friendly zone framing the downtown civic area is populated with cheerfully touchable bronze animals, a whimsical weather station, canny conceptual text-pieces, and more. The new mixed-used residential community in the former industrial area of the Pearl District boasts its own bronze menagerie, a number of ambitious water features both completed and in the works, and a shimmering kinetic sculpture planted on the median near world-renowned Powell’s Books. Both the City of Portland and Multnomah County dedicate 1.33 percent of the total construction costs of major capital improvements to public art.1 Over 22 public art projects were completed or in progress in 2003–04 alone. Additional programs fund a variety of temporary initiatives (one supported by fees generated from floor-to-area ratio [FAR] bonuses, for example) and enrich the civic collections of portable art through new acquisitions.

The bean-counter in all of us who get the SPUR Newsletter may need no additional proof of the intimate connection between public art and city planning. Certainly it’s the bottom line for politicians, who mostly want to know how much art is in their district and how much it cost. But such art-by-the-numbers analysis doesn’t begin to tell us the first thing about what sort of art adorns Portland. Nor does it address the reasons why both public art and planning seem to work there. So here is my thesis: art and planning work in Portland because they are part of a larger discussion about the shared values of the city. At its best, planning gives those values physical form in the “urban fabric.” At its best, art gives the public other points of access into those values, reflecting and reinforcing them as part of the urban landscape, but also adding new dimensions and new contexts, and acknowledging the insights of newcomers along the way. What follows is a series of picture-driven case studies that attempt to make another kind of map—not of art and development dollars, but of the common ground shared by public art and urban design in Portland.

Case Study #1: Living Rooms

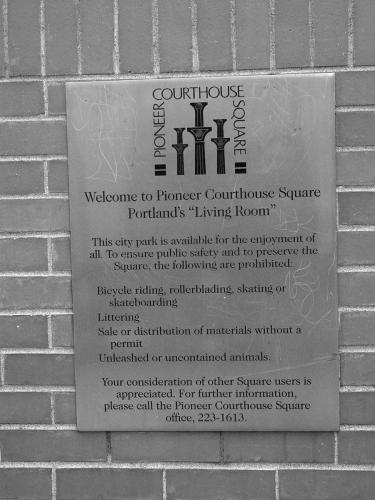

It is commonplace to cite Portland’s 200-foot blocks as the source of its walkability, but these intimate blocks also reinforce a sense of the city as a series of outdoor rooms. Portlanders treat their public realm like an extension of their living room—and it’s a lot like your grandmother’s living room. Lovingly furnished with the full complement of benches, tables, chairs, coffee stands, fountains, wayfinding devices, reading material (commemorative plaques and historical “talking rocks”), bike lockers, and public art, the public realm is also a place where a certain standard of behavior is expected, and a grandmotherly reminder about that behavior is also part of the furniture.

So deeply internalized is this sensibility that it is also susceptible to a gently unconscious irony. While Pioneer Courthouse Square is the City’s showplace outdoor “parlor,” the city of Gresham recently acquired its own, scaled-down version as a part of its transit center. A real downtown around the transit hub may still be a thing of Gresham’s new urbanist future, but the “living room” awaits, complete with bronze sofa and a softly glowing TV.

Plaque at the entrance to Pioneer Courthouse Square.

Proposed in the 1972 Downtown Plan, Pioneer Courthouse Square replaced a surface parking lot with a hugely successful public space. More than 21,000 people pass through "Portland's Living Room" each day.

"Gresham Central Living Room," public art installation, end of the Eastside MAX Blue Line in Gresham.

Case Study #2: Shared Visions

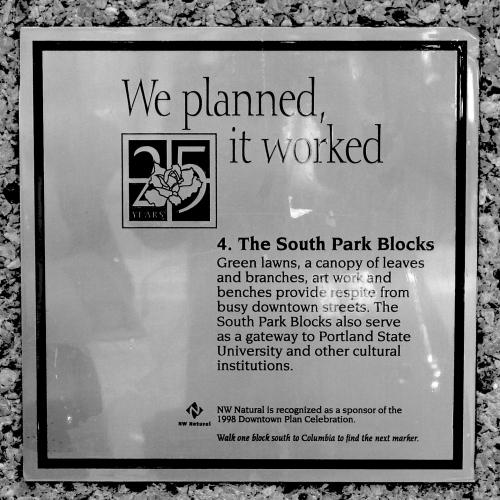

Portland’s public realm accompanies its reminders of the value of collective responsibility with gestures toward civic generosity that border on the obsessive. On the one hand, civic participation is both a weighty duty, perhaps best exemplified by the sober figure of Abraham Lincoln pondering the fate of his country, and a reason for local celebration in its own right. There are few cities where planning itself rates its own series of commemorative plaques (another one of my favorites is devoted to Catherine Sohm, who dedicated 37 years to Portland’s streetlight system—“Perseverance Pays,” the plaque admonishes each passerby).

On the other hand, responsibility has its rewards, perhaps best exemplified by the Benson Bubbler, whose multiple water fountains can serve four thirsty citizens at a time. Cute and compulsive, the 44 anthropomorphically surreal “bubblers” sprinkled around downtown seem readymade to take a turn with Mrs. Potts and Lumiére in Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast.” Can you hum “Be Our Guest?”

Fast forward to the 1990s, when a grassroots art group engineered the takeover of a busy southeast Portland residential intersection as community space, complete with a bottomless tea thermos and mismatched pottery mugs. The fact that the nineteenth century philanthropically minded tycoon that donated the water fountains and the late twentieth century communal hippies of City Repair defined public largesse in remarkably similar terms is itself a powerful argument for a powerfully persistent common culture. Such ideas continue to have their own legs in Portland. In January 2000, the City Council passed an ordinance that allows any group of citizens to petition to convert neighborhood streets into public squares—complete, one assumes, with their own refreshment stations.

The first 24 "Benson Bubblers" were given to the city by timber baron Simon Benson in 1912.

Plaque installed to celebrate the 1998 Downtown Plan.

Share-It Square at SE Sherritt and 9th Streets in the Sellwood neighborhood. 1996 conversion of a street intersection into a public square featuring a tea station (pictured), information station, produce station, Tree of Life, and painted pavement decoration by the community-based art collective, City Repair.

Abraham Lincoln, South Park Blocks. Bronze sculpture by George Fite Waters, donated by Dr. Henry Coe in 1928.

Case Study #3: Water First

In 1944, Oregon State College issued a devastating report. Oxygen levels in the Willamette River had been falling for decades, burdened by the unchecked dumping of septic and industrial waste. But now it was not merely a question of less oxygen. There were no detectable oxygen levels at all. The Willamette River was declared dead.

The comeback of the Willamette is not just evidence of an environmentally committed society. It is a reminder that it wasn’t always that way in Oregon. Such commitments are not just made once, they need to be renewed again and again. Investments in a healthy river open the door to rethinking “flow” and “circulation” in other places. Seeing water as a “multimodal highway” for work and for play, for humans and other species, encourages a metaphorical connection to shared streets. Learning how to share streets invites thinking on other shared spaces, such as public fountains, which weave the water through the city and bring thinking about the environment full circle. Transportation, environmentalism, and a cooperative approach to co-inhabiting space and the land go hand-in-hand.

A "living street" — pedestrians mix with mass transit near the Skidmore Fountain on Saturday Market Day.

Two views of the Ira C. Keller Fountain (completed 1970), designed by Lawrence Halprin near the Civic Auditorium at SW Third and Clay. One view gives a sense of the ensemble; the other records a homeless person on his early morning rounds.

Salmon Street Springs, designed by Robert Perron Landscape Architects. 185 jets spray water in patterns programmed by an underground computer according to the changing activity levels in the city. 1988.

A freeway used to dominate the northwest shore of the Willamette River. Now Portlanders stroll the meandering paths of Governor Tom McCall Waterfront Park.

Located between NW Johnson and Kearney in the Pearl District, the focal point of Jamison Square is a fountain that stimulates a shallow tidal pool by continuously recirculating treated water with energy-efficient pumps and motors. Treatment of the water allows kids (and dogs) to play and grownups not to worry.

Case Study #4: Big Boxes

Alternative forms of transportation hold pride of place in Portland’s civic imagination and this creative investment in pedestrian-friendly infrastructure helps to challenge corporate executives to make their own imaginative leap. When the Portland Development Commission slated the blocks between SW Columbia and Main streets and SW 10th and 11th avenues in Portland’s West End for new mixed-use development as “Museum Place,” Safeway came to them. Their downtown store, a rundown, sprawling one-story building with surface parking, was doing well enough (think Church and Market in San Francisco). But the new version—complete with bike racks prominently featured at the front entrance—takes the large-format grocery story to the next level of urban sensibility. A city that celebrates (and not just dictates) its transit priorities, signals to business interests—both locals and “chains”—that they would be wise do the same.

Case Study #5: Civic Follies

At some level, Portland doesn’t take itself too seriously when it comes to art—a healthy sense of fun was perhaps most famously exemplified when Portland Mayor Bud Clark donned a raincoat and boots to flash a statue of a female nude for a poster inviting citizens to “expose themselves to art.”

Thus it’s no surprise to find that aesthetic playfulness exists on both intimate and monumental scales. The super-sized Portlandia (only the Statue of Liberty is larger) may embody the true meaning of “folly”—an ornamental gesture of no practical value. But government workers, citizens, and visitors alike can step beneath Portlandia’s beckoning hand to discover a rotating program of temporary installations in the lobby of this government building—including a poetry station that allowed visitors in need of inspiration before “dealing with a difficult boss” or “preparing for a job interview” to listen in, or a sculptural dress nearly large enough for Portlandia to wear.

Such play may be impractical, but it is purposeful nonetheless. Portland’s temporary initiatives include not only the Installation Art Series in the Portland Building, but also In Situ Portland, a joint project of the Regional Arts & Culture Council and the Portland Institute, and Multnomah County’s Intersections program, that places artists-in-residence in City and County government agencies. In Situ Portland funds challenging temporary artworks throughout the public realm where they can act as dialogical flashpoints to spark conversations about art and community issues. Intersections invites artists to view all of Multnomah County as their studio, and to address the county’s employees, citizens, and neighborhoods as not only an audience but a cultural resource.

These are among the most forward-looking of Portland’s public art programs—they are deeply dependent upon a community that makes art a priority, but doesn’t allow the occasional true bit of folly to bring the program to a halt (to be sure, beauty is always in the eye of the beholder, but I wonder what the Chronicle’s Ken Garcia would have had to say about an installation of seven toilets allowing visitors to flush away the seven deadly sins?).

In the end, this is what temporary art does so well: it assures the public that there’s always a next time.

Of course, there are other lessons to learn from Portland, most significantly the decision on the part of the greater metropolitan region to establish the RACC in 1995. Much like your typical government-issue arts commission, RACC serves as the steward of public investment in arts and culture, funded in part by local, regional, state, and federal sources. But because it is a standalone nonprofit entity, it can also pursue its own supplementary funding—through an innovative workplace-giving program (that partly solves the conundrum of fundraising without competing with local arts organizations for foundation money), and through public art-management contracts with clients outside the Portland Metro area (Lewis and Clark College, for example, or the Children’s Hospital in Denver). An added benefit of this standalone status is that it allows RACC to write its own contracts, significantly expediting the public art process.

That said, such strategic organizational initiatives still wouldn’t amount to much in a city that lacks a strong sense of its own identity. This is why having a map in the mind of the linkages between art, urbanism, the habits of everyday life and the culture of community that shape the public realm can be so revealing. Make no mistake about it: the specter of a loss of consensus regarding planning and land-use issues that has so deeply unsettled Portland and beyond in the wake of the passage of Ballot Measure 37—if its promise is fulfilled—will have an unmistakable impact on the landscape of public art as well. And this important not merely because it foreshadows the failure of one pending neighborhood plan or another, or the dismantling of one scandalous sculpture or another, but because it foretells the loss of general agreement regarding environmental priorities, the balancing of individual and collective rights, and the ability to imagine any sort of community at all that make art—and planning—possible.