For San Franciscans today, Golden Gate Park has many meanings. When thinking about a public space such as this, or any, park, we must ask who the public is, what public space is, and how the space serves that public.

Parks of course are more than just physical places. Forty years ago, Jane Jacobs taught us that they only have meaning given to them by the uses which they support and which support them. This is because they are also social, cultural, and political spaces. In our highly fractured postmodern society, it sometimes seems like there is nothing we can agree upon. And in San Francisco land-use politics, nowhere have these battles been more hard fought in the last several years than around this almost mythic symbol, Golden Gate Park.

By this mid-2003 writing, although people are still wrangling over a few design details around the Concourse, many of the decisions that will take the 1,000+ acre Golden Gate Park and its institutions through the 21st century are made or nearly made-enough that at least the outlines of a newly reconceived park are set.

This issue of the SPUR Newsletter focuses on the park and its institutions and how they are evolving to take us forward in the new millennium. This introduction sets the stage for the major actors. Dr. Patrick Kociolek, Director of the California Academy of Sciences, describes that institution’s dual missions of research and education, and how the Academy’s proposed new structure, now in final design, advances these combined goals. In addition, we have the great treat of an interview with Renzo Piano, the world renowned architect who is creating the new Academy. Harry Parker, Director of the Fine Arts Museums, speaks on the meanings of an art museum today, and how the spectacular new de Young, well under construction in Golden Gate Park, meets both that promise and also takes and gives meaning to its setting. Michael Ellzey, the Executive Director of the Golden Gate Park Concourse Authority, shows how the Authority’s multiple projects help knit it all together. And finally, Elizabeth Goldstein, the General Manager of the Recreation and Park Department, discusses the park overall, its challenges, and how Rec and Park is working to improve it.

The story of American parks, and the historic setting of Golden Gate Park, goes back to the 1850s when an American farmer/journalist traveled to England to study progressive farming techniques. On his travels, he happened upon Birkenhead Park, outside of Liverpool, one of the world’s first “rural pleasure grounds.” This was an era, here and in England, of rapid urbanization, railroad building, and immigration. This traveler, Frederick Law Olmsted, like other contemporary social reformers, saw the debilitating effects the rapid pace of life and crowded, unsanitary conditions were having on new city dwellers who went from tilling the earth in rural villages to living in tenements and six-day-a-week jobs in urban factories.

A few years later, in 1858, Olmsted and his partner Calvert Vaux were the competition-winning designers of the “Greensward Plan” for Central Park. In that time of rapid urbanization, they sought to bring public open spaces to a population suffering from the pressures of their substandard working and living environments. That park, and others which followed, were designed to be “rural retreats” where the poorer citizens could interact with “nature” and where citizens of all classes and backgrounds could meet and socialize. The park was widely advertised to doctors and ministers, with flyers in tenement houses and churchsponsored children’s picnics. Olmsted believed that parks would also help keep the wealthy in the city and stern the flight to the suburbs, which was robbing cities of both leadership and taxes.

In 1865, the citizens of San Francisco petitioned the Board of Supervisors for such a park, and in a few years Golden Gate Park was underway. Beginning in 1871, Hammond Hall was appointed engineer and superintendent of the park. Like Central Park, the purpose of Golden Gate Park was to be a rural pleasure ground. City fathers in San Francisco and across the country saw cities as a necessary evil, and open space an antidote to that evil. The design of pleasure grounds was to be as “natural” as possible to bring the feeling of the countryside into the city and to evoke the visitor’s memory of the country and the instinctive attraction it holds. These Victorian pleasure grounds were designed to be curvilinear, pastoral, and a middleground between untamed nature and the orthogonal city. Buildings, if any, were to be exotic and rustic and hidden in the landscape. Water bodies were to be flat and serene. Only native plants were to be used, as exotics would “overstimulate the mind.”

Iconic as Golden Gate Park is, since 1865, society, recreation, and this park like all others have undergone numerous transformations. And I would submit one of the reasons Golden Gate Park is still beloved (unlike scores of parks nationwide which are unloved and effectively abandoned) is that it has adapted and changed with society. Like living organisms, those that survive are those that are most able to change.

No longer the Victorian pleasure ground pretending to be a faux wilderness for those without a horse and carriage to take them to the real countryside, Golden Gate Park has gone through a number of societal and design changes over the years.

Park records show that by 1881, in a pattern all too familiar to today’s San Franciscans, the park was deteriorating from lack of maintenance - trees dying from lack of water, gardeners laid off, and bills unpaid. By 1890, a change of city management brought in a first-rate gardener, John McLaren, who remained park superintendent until his death in 1943. However the shaky finances have come and gone with regularity throughout the century.

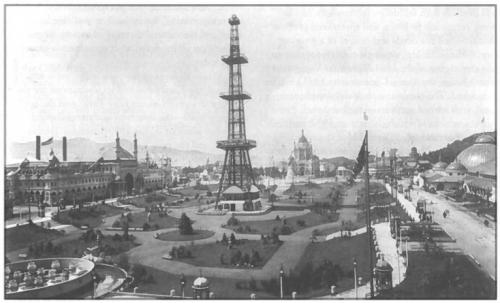

Almost from the start, the rural pleasure groundwas overlain with buildings, monuments, institutions, recreation facilities, and specialized gardens that reflected the needs and desires of a growing city. Perhaps the biggest single catalyst for change was the staging of the 1894 Midwinter Exposition in what became the Music Concourse in 1895 after the fair closed. The concourse itself developed piecemeal, with several versions of the band shell (the current version of which dates from 1900) and the various fountains which were added through 1926. The de Young Museum building evolved out of the exposition, beginning in 1895 and replaced in 1921; the new (now old) Asian Art wing was added in 1966; and the Steinhart Aquarium/Academy of Sciences was built in sections beginning in 1916.

The Concourse as it looked in 1984. Photo courtesy Marilyn Blaisdell collection.

As Elizabeth Goldstein notes in her article in this issue, while each of these “urban” facilities is in contradiction to the original idea of a rural pleasure ground, this area is the most popular in the park and attracts more visitors than anywhere else. It has been the locus of the biggest civic lights, as everyone wants to recreate “right here” even as other, more westerly areas of the park are decidedly less used.

But this island of urbanity centered on the Concourse does not represent the only nonrural buildings in the park; there are some 25 other buildings the park’s founders would have thought inappropriate—ranging from the Conservatory of Flowers (1877) to clubhouses for various sports (beginning with the first tennis clubhouse in 1901) to a nowgone casino (1882), more than one house (and most prominently McLaren Lodge of 1896), two police stations, and several stadia. These uses and structures would not have met the original social reformer’s ideas of calming the body and mind with rural scenery, neither would the various ball fields, tennis courts, riding rings, and such which began being installed in the park in 1893.

We have gone far beyond native vegetation with a number of specialized and showy floral areas, beginning with the Rhododendron Dell in 1892 to Queen Wilhelmina’s Tulip Garden in 1963. And of course, these are representative of some of the loveliest and most popular features in the park.

Olmsted held Statuary in special opprobrium. And does Golden Gate Park ever have statuary-more than 30 by a quick count, from the 1885 Garfield Monument to the 1963 Thomas Masaryk Bust, each one of which has or had a special constituency. Even poor John McLaren, who likewise hated sculpture in the park, is commemorated with his own statue!

All of which goes to say that, in the 21st century, Golden Gate Park is a long way from the rural retreat that was thought appropriate 130 years ago. And that’s a good thing. Styles of recreation, the widespread availability of public and private modes of transportation, the increase in available leisure time, and the cultural diversity of society, to mention a few, have all impacted what constitutes a successful park today.

While all areas of the park are valuable and utilized, the Concourse and its institutions are the biggest draws in Golden Gate Park. And the landscaping itself—the fountains and the pollarded London plane trees, the 1900 Spreckles Temple of Music, and the park benches—is urban in character.

Human beings are fundamentally social animals and, at least some of the time, we want to recreate around others of our species. This is both the magic of the Concourse and the challenge, leading to the competition for space and right-of-way between outdoor recreationists, museum-goers, pedestrians, bicyclists, automobile drivers, and transit passengers-all of whom lay some claim to the Concourse.

It has been said that in this city of immigrants, we each think that the city was perfect the day we arrived. If you were here in 1965, chances are you rued the construction of the Transamerica tower; if you’ve come here since, it’s a famous part of the local landscape. Likewise, the design features in and around the Concourse have completely changed many times-the de Young site was at first sand dune, then informal landscape, then an Egyptian revival building, then Spanish Churrigueresque (added to many times), then stripped down. And now a spectacular new building is under construction. The 1894 exposition had a 200-foot observation tower in the middle of the Concourse and a largely open curvilinear landscape. The present day pollarded London plane trees in the Concourse bowl and the palms in front of the de Young are all later additions. Those who wish to the landscape or architecture in a particular moment in time would do well to consider it’s just that—what happens to be there at this moment in time.

In a park of more than a thousand acres, it is symbolic of our civic dysfunction that this few dozen acres became the cause célèbre both by those who wanted to freeze it in its most recent incarnation and those who wanted to hijack it for their favorite use. I hope that this issue of our newsletter helps put the park in perspective and helps us all understand that its remarkably flexible design matrix can be adapted to changing styles of use during the next 130 years just as it has for the last 130 years.