In the early months of COVID-19, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) convened a 32-member Blue Ribbon Transit Recovery Task Force to guide the future of the Bay Area’s public transportation network as the region adjusted to new conditions created by the pandemic. Among other issues, the group of transit agency managers, advocates and local lawmakers recognized that the region’s fragmentated public transit system can discourage people from riding transit. To stimulate recovery of both the Bay Area’s transit system and its economy, policymakers are now pushing for changes that will welcome riders back and make regional transit work for more people.

The institutional setup of the Bay Area’s regional public transit system is one of the most complex and fragmented in the United States. Regional riders navigate more than two dozen unique public transit operators, and each of them independently plans and operates its system. Many transit operators serve just one county and rely on funding sources generated in that county, creating powerful incentives for transit agencies to focus on local riders and local trips. For regional transit customers taking trips across multiple transit operators, this local focus can mean a confusing array of fares and maps, gaps in service that create long waits and difficult transfers, and uncoordinated capital planning and investments.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In fact, there’s growing recognition that it can’t be this way. Transit ridership continues to be depressed after more than a year of shelter in place, and agencies face an uphill battle to restore ridership to pre-pandemic levels. Additionally, the Bay Area’s climate goals rest in part on making sure that 20% of all commute trips are taken on transit. Even before the pandemic, that number was only 13%. A fragmentated transit system can frustrate and discourage people from riding transit for regional trips, making it even harder for the region to recover.

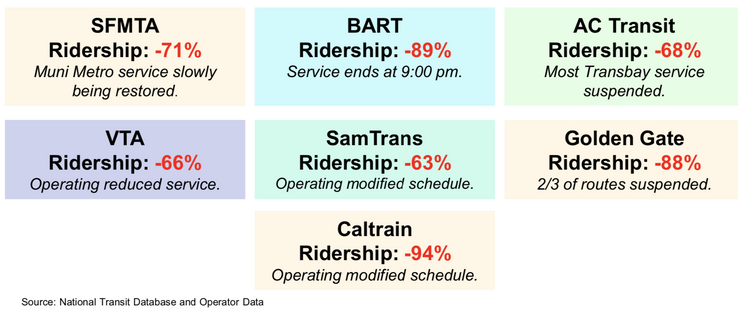

Shelter in Place Impacts on Bay Area Transit

Ridership and service levels, February 2021 vs. February 2020

Source: MTC, Blue Ribbon Transit Recover Task Force meeting, April 26, 2021

Though the majority of transit trips are local, improving regional trips is important for economic recovery, for minimizing local air pollutants, and for ensuring that local service can move without being stuck in traffic. Imagine how congested San Francisco would be if those who used to commute into the city by BART, transbay bus, Caltrain or ferry drove into the city, or if they all got into cars after disembarking from their trains in order to get to their destinations. The city simply does not have room for more cars.

Together, MTC, legislators, transit agencies and advocates are working to scale up existing integration efforts and accomplish more integration sooner. MTC’s Blue Ribbon Transit Recovery Task Force is working to prepare recommendations to help integrate the Bay Area’s disparate transit systems so that they function like one rational, integrated regional network. Assemblymember David Chiu, a member of the Task Force, has introduced a bill to build on this coordination and ensure that it continues beyond the pandemic.

AB 629, the Seamless and Resilient Bay Area Transit Act, would require transit operators and MTC to make headway on integration efforts that can be significantly advanced through coordination between agencies. The bill would advance near-term improvements to customer experience, including piloting a regional fare pass, implementing cohesive wayfinding and transit maps, and providing riders with real-time travel information. These improvements would build on ongoing voluntary coordination efforts, such as MTC’s fare integration business case, the launch of a uniform regional discount for low-income riders (ClipperSTART) and efforts to improve transfers. For instance, for the first time, BART and Caltrain have put in place a timed cross-platform transfer at Millbrae Station. AB 629 also lays the foundation for a coordinated regional transit priority network to keep buses and very high-occupancy vehicles flowing quickly and reliably. As a longtime advocate for creating an integrated transit network, SPUR supports this bill because it advances integration actions that would meaningfully and quickly improve customer experience and expand access to high-quality regional and local bus service.

The task force and AB 629 are important opportunities to create a more integrated regional transit network that can better support a sustainable, equitable and prosperous region. To make the most of these opportunities, SPUR believes six principles should guide this work:

1. Early integration actions must improve regional transit access and mobility, especially for people with low incomes and people of color, who are overrepresented at the low end of the income spectrum.

Integration efforts should help remedy longstanding disparities in access to affordable public transportation. MTC found that regional fare integration significantly benefits lower-income residents and could add between 40,000 and 70,000 new weekday boardings. An early action could include eliminating transfer penalties and making the newly launched ClipperSTART fare discount program permanent.

Creating a transit priority network — via transit-only lanes and other tools — improves frequency, speed, reliability and comfort on heavily used routes. Because this helps make riding the bus faster and more fair, it is a critical part of SPUR’s vision for a more equitable regional and local transit network. Riding the bus should be faster, not slower, than driving but most regional and local bus trips are significantly slower and less reliable than driving alone. Bus service is also too scarce — a problem worsened when buses are stuck in traffic because it increases the cost to maintain service levels, let alone grow them. This has a particularly harmful impact on low-income, Black and Latinx populations because a higher proportion of people who identify with these groups are transit dependent or ride transit regularly.

At the same time, creating a transit priority network for buses that operate across counties may help increase the percentage of people who take transit. In the last decade, BART and Caltrain saw the highest rates of ridership growth, a trend driven partially by the fact that trains offer faster and more reliable speeds (especially once Caltrain added its “baby bullet” express service). Meanwhile, AC Transit, Golden Gate Transit and VTA bus services all saw dips in their ridership levels. Enabling frequent, all-day and reliable service is one of the most essential things the Bay Area can do to build ridership.

2. Integration efforts must safeguard and improve transit service levels in dense, urban places.

The Bay Area needs to integrate urban and suburban communities with an effective regional transit network. However, these efforts should not come at the expense of frequent local service in the region’s urban core. San Francisco has the highest density of people and jobs and a mix of origins and destinations in close proximity to each other. As a result, it’s also where most transit rides are taken. Other countries around the world have solved this challenge by setting minimum service levels for high-demand corridors, and local governments can choose to provide and provide more service, but not less, based on their individual goals and needs.

3. Integration efforts should create a service-based vision for the regional transit network.

SPUR believes that the Bay Area needs a core transit network that is designed to act as the region’s stable, high-capacity, high-frequency transportation backbone. Voters do, too. Voters cited a lack of frequency as a major barrier to public transit use, and over 70% of focus group participants in a 2020 study said that there should be a regional plan to guide transportation investments. While the state and federally mandated regional transportation plans (the RTIP and Plan Bay Area, respectively) are a step ahead of most regional transportation plans around the country, they do not lay out a plan for a high-capacity, high-frequency regional transit network. Instead, they are still developed by analyzing and selecting from a menu of projects submitted by local jurisdictions and transit operators (known as a “project-based plan”). In the past, these types of plans have created a tendency to over-invest in suburban capital projects and projects that duplicate service or compete for riders, that do not add up to an integrated regional transit network and to underinvest in urban infrastructure and core transit service.

Instead of a project-based plan, the region should adopt a service-based regional transit plan with abundant regional and local service. Such a plan would outline a pathway to give people what they consistently ask for: more frequent and more reliable buses and trains, and improved connections so that they wait less and get where they need to go quicker. The service-based plan would be based on projected regional travel patterns and would take into account which land uses and demographic factors generate the most transit riders. A focus on service would help the region invest limited funds wisely; projects are selected based on how cost-effectively they deliver frequent, reliable service to key locations and how successfully they integrate into the regional network. This would better position the region to adequately invest in maintenance and upkeep, select more cost-effective solutions to connect people and places. A service-based vision would help the region build projects that are more than the sum of their parts.

Project-Based vs. Service-Based Transportation Plans

Source: SPUR report A Regional Transit Coordinator for the Bay Area

This service-based plan for the Bay Area should initially focus on regional trips and connections with local services at regional hubs. However, individual counties or groups of counties should also develop similar service-based plans for local transit as well.

4. Governance changes are necessary and should be crafted with care.

Voluntary interagency coordination can go a long way. However, in some cases it’s not enough. Despite significant coordination on fare payment since the launch of the Clipper Card 11 years ago, the Bay Area still doesn’t have a regional transit pass that works on all operators. We believe that the Bay Area needs to join other regions around the world that have addressed issues of fragmentation by establishing a transit coordinator, an institution empowered and accountable for establishing policies and housing formal collaboration efforts in order to have a more cohesive network. Now is the time to carefully study changing the institutional structures of regional transit in order to deliver improved service, gaining a fuller understanding of public benefits and tradeoffs. These governance reforms could include granting agencies new authorities, transferring authorities from one agency to another, targeted consolidations among operators, changing board compositions and more.

A key next step for MTC’s task force is to complete a business case for the management of a regional transit network, which will study potential governance reform options. Additionally, the recommendations from the network management business case must become integrated into future transit funding opportunities.

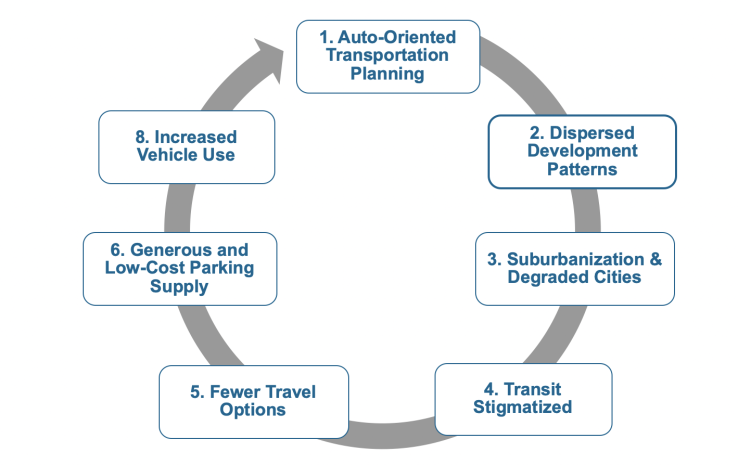

5. Governance reforms must acknowledge that many transportation challenges are actually land use challenges.

The primary reason people do not take transit in the Bay Area is because we have built the region around driving. Transit goes underused because too few homes and jobs are located in communities that are compact and walkable enough to be served effectively by transit, and government provides too many explicit and implicit subsidies that encourage driving. The resulting congestion makes transit slower and less reliable, reducing ridership further. The scarcity of transit further encourages auto-oriented development patterns, with origins and destinations that are far apart and urban design that discourages walking. Transit agencies can’t solve this problem, but state, regional and local government can.

Cycle of Automobile Dependence

Source: SPUR. Adapted from Victoria Policy Institute, “Evaluating Transportation Land Use Impacts”

6. Some integration efforts require additional funding and capacity, and new revenue should be directed to support these efforts.

For instance, instituting a regional transit pass could reduce revenue to transit operators in the near term, even though gains from increased ridership could compensate for these losses in the long run. Equipping buses with transponders to provide real-time information and creating a regional transit service vision would also require resources. Federal relief and infrastructure funds offer an important infusion of funding for one-time or low-cost integration, just as federal funding was used in 2020 to help support transit operators who opted in to ClipperSTART. Additional funding from future local or regional funding measures, or a new federal program focused on service, could be used to reimburse operators for any revenue losses that might arise from the more costly integration efforts. A lack of immediately available funds should not stand in the way of less costly integration efforts or planning for those that have a higher upfront cost.

Now is the time to work together with urgency and conviction to create a more integrated regional transit network. With more consistency and fewer barriers across regional transit, we will see higher ridership and shorter trip times. Communities will have confidence in putting new growth near regional transit, and we will be more likely to meet our regional climate and equity goals.