Miami is known as a global destination for hospitality, but it also has a reputation as a deeply unequal place. The greater Miami metro region has a poverty rate of 14.3%, among the highest in the country.1 While the region boasts high-profile foreign investment, its middle class continues to shrink and the local economy is dominated by low-paying service jobs. Miami’s communities of color are disproportionately affected by these dynamics: Latino and black Miamians are twice or 2.5 times as likely, respectively, to live in poverty as white residents are.

During SPUR’s study trip this year, our conversations gave us a small window into these challenges, particularly as they play out around housing affordability and access to transportation. But we also learned about projects that have the potential to make significant progress toward improving those issues. Here are a few examples:

A master plan for affordable housing.

The median rental price in greater Miami is just over $2,000 per month, on par with other large metro regions like Seattle ($2,150) and Washington, D.C. ($2,079). However, Miami’s median income is far lower, reflective of an economy driven by the service industry, with wages that remain stubbornly low despite economic growth and rising housing costs. The median income in the greater Miami region is just over $31,702 (for comparison, the national median income is $36,693, and in San Francisco it’s $52,902). Six out of ten adult residents in the greater Miami region spend more than 30% of their incomes on housing, one of the highest rates of housing burden of any large metro in the nation.2 Many agree that housing affordability is compounding Miami’s economic and racial inequality. Service class workers, many of whom are black and Latino Miamians, are at least two times more housing cost-burdened than other communities in the region.3 Last year, the city of Miami partnered with Miami Homes for All, a nonprofit advocacy group, to set a goal of creating or preserving 12,000 units of affordable housing by 2024. Their strategy identified housing pipeline opportunities in public housing redevelopment, older building stock preservation, permanent supportive housing and from other sources — and calculated the units needed from each to meet the city’s goal. The work also identified policy changes to deliver the new and preserved housing, including zoning code changes, a vacancy tax and reduced property taxes. Now the city, together with researchers from Florida International University, is using this data to create an affordable housing master plan. The first of its kind in Miami, the master plan will further quantify the city’s housing need and propose policy interventions to address the shortage.

A community-led redesigned bus network — and a regional rail future.

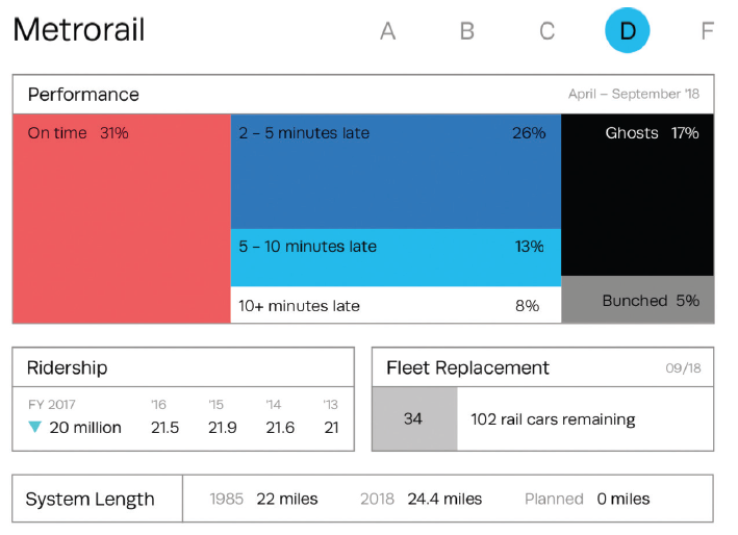

Like most American cities, Miami was built with the car in mind. Its growth went hand in hand with suburbanization and mass infrastructure investment for the car. Today, Miami has some of the worst traffic congestion in the country: Drivers lose an average 100 hours in traffic each year, and the region’s economy loses $4 billion in revenue.4 Rising housing costs have pushed many low-wage workers to the suburbs and farther from their jobs, creating longer commutes into job centers in downtown and Miami Beach. And as is true in other metro regions across the country, transit ridership is declining at an alarming rate. Between 2013 and 2017, the county bus system, MetroBus, lost 25% of its riders.5

In 2018, Transit Alliance Miami, a membersupported transit advocacy group, completed an audit of the county bus system. The research revealed crippling service cuts, poor reliability and misguided network design. Most riders waited an average of 30 minutes for the bus, and the number of buses that never showed had increased by more than 150% from the previous year. Core routes had been cut or discontinued, further driving down ridership.6 In response, Transit Alliance Miami, together with county Mayor Carlos Gimenez and the Department of Transportation and Public Works, launched the Better Bus Project, the first communityled bus system redesign in the country. In June of this year, the team began surveying riders across the county, setting up portable workshops at stations, and plans to partner with community groups and host a series of meetings with county officials and others before presenting a new network plan to the County Board of Commissioners.

Figure 1. Better Grades for Buses?

Focusing on Metrobus makes sense: The system serves two-thirds of all public transit trips in the county, is the most flexible and has the most potential for quick improvement. Transit Alliance Miami and its partners plan to release network concepts this fall.

Meanwhile, the county is focusing on the future of regional mobility with passenger rail and bus rapid transit. Beginning in 2016, the Miami-Dade Transportation Planning Organization developed a plan that outlines investments in rapid bus and mass transit options across six key corridors in the county, which would serve 1.7 million people (more than 63% of the county’s population).7 Projects include the new multimodal station in downtown Miami that connects rail, bus and trolley systems as well as the nation’s only privately owned and operated intercity rail system, Virgin Trains USA. The express rail system connects the region to Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach (and eventually Orlando), and the station is being developed alongside high-density affordable housing. Demonstration projects are under way as the county seeks to fill funding gaps.8

Lessons for the Bay Area

Miami faces many similar challenges related to housing affordability and mobility, which compound inequality. Here in the Bay Area, we might learn from the civic power and the partnerships that have helped deliver Miami’s success thus far. We were struck by the cross section of philanthropists, institutions, advocates, developers and others who have mobilized to weigh in on — and in some cases define — a vision for the future of the city and the region.

Endnotes

1 Richard Florida and Steven Pedigo, Toward a More Inclusive Region: Inequality and Poverty in Greater Miami, Miami Urban Future Initiative, 2019.

2 Richard Florida and Steven Pedigo, Miami’s Housing Affordability Crisis, Miami Urban Future Initiative, 2018.

3 Florida and Pedigo, Miami’s Housing Affordability Crisis.

4 Richard Florida and Steven Pedigo, Stuck in Traffic: For Greater Miami to Become a Leading Startup Hub, Better Mobility Is a Must, Miami Urban Future Initiative, 2019.

5 2018 Mobility Scorecard, Transit Alliance Miami, 2018. https://transitalliance.miami/campaigns/mobility-scorecard.

6 Where’s My Bus? Transit Alliance Miami, 2018. https://transitalliance.miami/campaigns/where-s-my-bus/ridership.

7 Strategic Miami Area Rapid Transit (SMART) Plan brochure, Miami-Dade Transportation Planning Organization, 2019. http://www.miamidadetpo.org/library/smartplan-brochure-2019.pdf.

8 Despite some success, the SMART plan has been criticized for misguided corridor planning, delays and cost overruns. Some advocacy groups and others are calling for a renewed approach and new leadership.