The story of New Orleans is the story of water. Fresh and salt. Life’s blood and mortal threat. It is the highway, the builder of land, the purveyor of food. But the water also takes away. The unforgettable images of Hurricane Katrina’s aftermath and the stunning disappearance of the Louisiana coast are just the latest reminders of the precariousness of the city. In the wake of the catastrophic storm, with the seas rising and the land sinking, New Orleans was shaken awake, and is now taking action to secure its future. Planners, engineers, policymakers and residents are tackling some of the pressing challenges that were neglected for generations, yielding exciting ideas and impressive results.

Context: Delta, River and City

The Deltaic Plain of southeast Louisiana is, in geologic terms, brand new. It was made of fine silt that washed down the Mississippi River system as glaciers retreated after the last ice age. Heavier rock, gravel and sand have long since dropped out of suspension by the time the river reaches the continent’s flat, low-lying underbelly, and the naturally occurring soils contain only silt and clay. Spring floods overtopped the river’s banks, building land out of these fine sediments into the Gulf of Mexico and raising natural levees – so the high ground is, counter-intuitively, closest to the river, and slopes down to ‘backswamps’ of cypress some distance from the banks. Periodically, the slow moving river found more direct routes to the gulf, and rushed into a new channel, building vast tongues of new land around distributaries (the opposite of tributaries). This process, which has occurred seven times in the last five millennia, has been likened to a garden hose, flopping about in slow motion on a massive scale, and it established the basic landforms of the delta.

For European imperial powers, the Mississippi River system promised a gateway to the thickly wooded American interior and the Great Lakes beyond. But where upstream it provided a navigable thoroughfare, its mouth was elusive, lost among the marshes, bayous and barrier islands of the Gulf coast. Once La Salle had sailed down the river into the Gulf in 1682, the French crown sought to secure his claim to it by establishing a military and colonial capital to control its mouth. In 1718, after considerable controversy, Jean Baptiste le Moyne de Bienville prevailed in his campaign to locate the capital 100 miles upstream, where it would be safe from hurricanes and, most importantly, accessible by a short portage from Lake Pontchartrain via Bayou St. Jean, eliminating a long, treacherous meander up the river from the Gulf. Here New Orleans was sited, and the French Quarter platted on the riverbank’s natural levee. In the 19th century, the city grew rich as the toll-taker and transit point for the economic expansion of America’s interior, and it developed a uniquely cosmopolitan culture blending French, Spanish, African, Cajun, Creole and Native American influences.

From its beginnings, New Orleans was subjected to periodic flooding, and the natural levees were repeatedly raised and reinforced. Backswamps were drained with ditches and canals wherever possible to facilitate the city’s growth, but flooding and drainage were chronic problems, and the higher ground along the riverbank remained the most privileged property. In the early 1900s, new pumping technology allowed comprehensive drainage of low-lying areas and the city expanded quickly toward Lake Pontchartrain. As ground water was pumped away and trapped organic matter and oxidized, land subsided dramatically, leaving much of the city below sea level for the first time. Without the threat of regular flooding, traditional architecture – with its elevated ground floors – gave way to slab-on-grade tract homes, which could easily flood or simply float away. As levees were built up along the river, lake and canals, and land subsided, much of New Orleans became a series of bowls or basins, in which rainwater would collect and could be drained only by pumping into the outfall canals. Because the canals were open to Lake Pontchartrain, the city’s front line of flood protection extended deep into the city’s populated interior, with long stretches of under-engineered canal walls and levees exposed to the full force of storm surges.

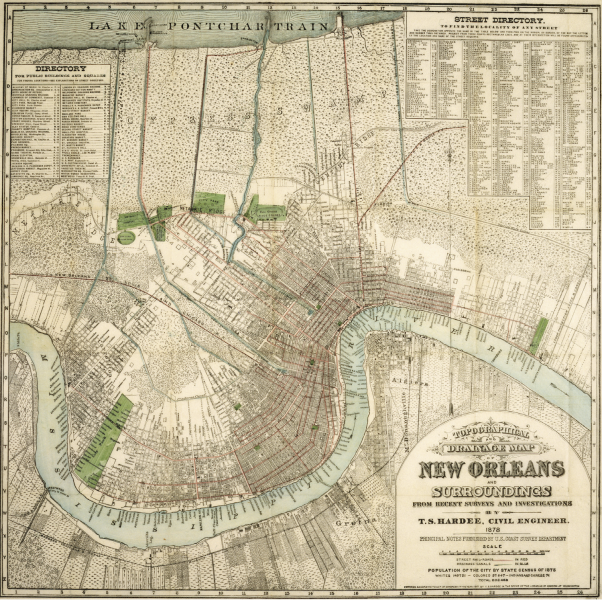

Topographical and drainage map of New Orleans and surroundings

New Orleans was built on the high ground of the Mississippi's natural levee, where the Bayou St John offered a short portage to Lake Pontchartrain. By the 1870s, drainage canals had been dug through the cypress swamps, but flooding remained a chronic problem. Hardee Map, source: The Historic New Orleans Collection.

The mismanagement of the Mississippi delta region compromised its intrinsic resiliency. With the river hemmed in by levees, coastal wetlands were starved of flood-borne sediments and began shrinking rapidly. Shipping canals, petroleum pipelines and levees cut direct channels through which storm surges could be carried inland instead of buffered and dispersed. These issues were well known, and hurricanes in 1947 (unnamed) and 1965 (Betsy) resulted in severe flooding and loss of life. A protracted debate among the US Army Corps of Engineers and local agencies about the right way to protect the broader region and prevent stormwater flooding resulted in the compromised system of raised levees and canal floodwalls in place on August 29, 2005.

Hurricane Katrina made landfall as a Category 3 storm that morning. The city of New Orleans was spared a direct hit, and damage from winds and rain was limited. What devastated New Orleans was the storm surge – water pushed inland by the passing hurricane, carried and concentrated by ill-considered levees and navigation channels. Levees along the channels and the Industrial Canal were overtopped and then breached, and water poured into eastern New Orleans neighborhoods.

The surge delivered 10-15 feet of water to Lake Pontchartrain and into the outfall canals in the heart of New Orleans. The levees along the lake withstood the storm surge, but the 17th Street and London Avenue canal walls and levees failed catastrophically. Even as the storm surge receded, water continued to pour into the city through breaches until more than 80 percent of it lay underwater. Many pump stations were overwhelmed or lost power and failed. In the weeks that followed, more than 250 billion gallons of water were pumped from the city.

The human costs of this failure of engineering, governance and emergency response have been widely reported. Of 1,833 Katrina-related fatalities, more than 1,500 were in New Orleans. Many drowned in their own homes or in hospital beds. While nearly 90 percent of residents were able to heed evacuation orders, tens of thousands of the poorest and least mobile were left behind to fend for themselves under appalling conditions. Katrina provided a vivid illustration of social vulnerability, where climate, policy and inequity come together.

Establishing Resiliency: Three Lines of Defense

For the next storm and beyond, New Orleans needed a new way to manage water both inside and outside the city, addressing both rainfall and coastal storm surges. Hurricanes and hurricane-induced weather — and 60 inches of rainfall in a normal year — have always been part of life on the subtropical Gulf coast, but due to climate change, the potential for devastatingly large hurricanes to recur is increasing. Since Katrina, the city, state and federal partners have planned and invested in a suite of flood-protection measures to lessen the damage of future storms. Some of these measures even provide more than flood control, taking on the massive project of reversing the environmental damage that increased the region’s vulnerability to storms in the first place.

As the measures get built out over the next decade and beyond, three layers of protection — “lines of defense,” in the Dutch way of thinking — will surround New Orleans. Furthest out (the first line of defense) is a $50 billion series of coastal restoration projects designed to slow the rapid loss of land and wetlands on the Louisiana coast and in the Mississippi delta. Closer in is an engineered perimeter of levees and pump stations that surround New Orleans, constructed specifically to reduce the risk of hurricane damage to the city. The third line of defense, still a conceptual plan today, is a new urban water plan that would direct and retain stormwater inside the city, within parks, bayous and new wetlands without having it overwhelm the city’s fragile and overtaxed network of pipes and pumps.

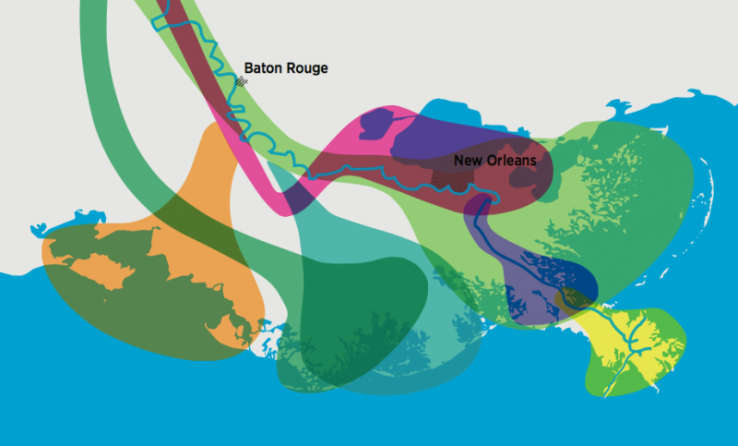

Deltaic Cycles of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi Delta grew over just the last five thousand years, as the river deposited flood-borne sediments. Periodically, the river found a new course, creating seven "lobes" of land in succession until human engineering fixed its current course.

Each of these barriers or lines of defense is being designed and constructed separately; there is no grand strategy linking them. But each idea, in and of itself, is truly at the forefront of innovation in water management and climate adaptation in America today. Together, they suggest a direction for resilience- building that other coastal cities and regions – like our own — can look to as we face increasing risks from future storms and sea level rise.

1. The Louisiana Coast: Reversing Coastal Land Loss through Wetland Restoration

Louisiana’s coast is nationally significant. It produces 25 percent of the nation’s seafood, ships 25 percent of the nation’s exports through its five large ports, and is the second largest natural gas producer and the third largest petroleum producer and refiner in the country. It is home to two million people and contains 40 percent of the nation’s wetlands. It is also significantly threatened by land loss. Today, Louisiana loses about 16 square miles of land annually and has cumulatively lost over 1,800 square miles of land since the 1930s. Although the rate of loss has generally slowed since the 1980s, recent hurricanes have quickly made up the difference: Between 2004-2008, Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Gustav and Ike turned 328 square miles of wetlands into open water, exceeding the cumulative losses of the previous 25 years [1].

Coastal land loss occurs for many reasons. Hardening the Mississippi River into its current channel in the 1930s, dredging the river to maintain shipping lanes, and building levees and spillways to divert flood flows have all deprived wetlands from receiving the sediment and fresh water they need to survive. Oil and gas pipelines have cut thousands of miles of channels into marshes and allowed salt water to penetrate inland. Land is subsiding due to drainage projects that have increased soil oxidation and compaction, and because the land itself is soft, sinking mud is not regularly being replaced by river-carried sediment. On top of all of this, there is slow and steady sea level rise, poised to accelerate as oceans warm and glaciers melt. Southeast Louisiana’s experience today is a glimpse of the future for coastal regions around the world that will all have to confront sea level rise. But because of accelerated land loss and subsidence, Louisiana is experiencing it at an especially terrifying rate.

In response to this threat, and to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, the state of Louisiana established the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) in 2005. The establishment of a single entity to represent the state in a coordinated way and to receive (and be accountable to) federal funding for coastal restoration was a key move. Prior to 2005, restoration and coastal management planning was managed by numerous local governments and special districts. CPRA was statutorily required to develop a comprehensive coastal master plan that would consider both hurricane protection and coastal wetland enhancement, and be updated every five years.

The 2007 and 2012 Coastal Master Plans each evaluated nearly 400 projects (and selected over 300 to fund) toward a 50-year restoration plan. The projects were of many types: structural flood protection like floodgates, pumps and levees; restoration projects like oyster barrier reefs, marsh creation and sediment diversion; and nonstructural projects like elevated housing and floodproofing. The projects were evaluated using risk reduction models, decision support tools and extensive community meetings and public outreach. Under two scenarios of land loss rates, at Year 50, the master plan projects together are expected to reduce financial damages from flooding between $5.3 and $18 billion annually. Since 2007, CPRA has secured $18 billion of state and federal funds for restoration and has built over 250 miles of levees, constructed 45 miles of barrier islands, and designed or constructed over 150 projects.

This scale of planning and rate of implementation far outpaces what we normally see in coastal planning efforts or restoration projects, perhaps especially in California. CPRA’s innovation is in having one comprehensive plan for the entire state’s coast – informed by science — and an evaluation process that considers the combined benefits of multiple interventions. Although CPRA says there was “no optimal solution” but rather a balancing of tradeoffs – risk reduction, near term benefits, long term sustainability, maintenance of the fresh and saltwater balance – in selecting projects, its success was in deploying enough resources and projects both to achieve the plan’s broadest objectives and to mitigate political risk. The Bay Area, home to hundreds of local jurisdictions and special districts (like California as a whole), might take a page from Louisiana’s playbook as we move from a project-by-project approach to managing our shoreline towards a more comprehensive adaptation and resiliency plan.

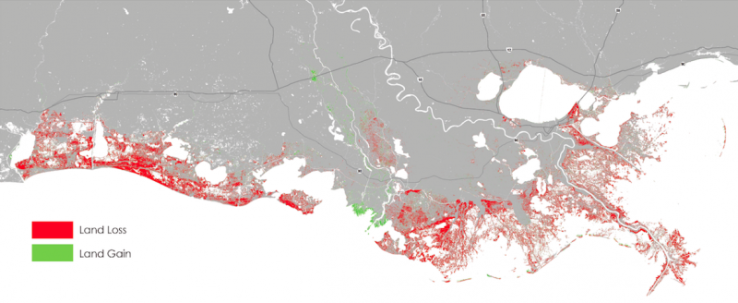

Potential coastal land loss on the Louisiana coast

This image shows what happens if nothing is done to protect the coast: 1,765 square miles of land may be lost by 2050 are shown in red; land gain in green. Source: Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), 2012 Coastal Master Plan.

2. The Hurricane Damage and Risk Reduction System: Building a Perimeter Wall Around New Orleans

The entire New Orleans region stands to benefit tremendously from slowing land loss and restoring the wetland ecosystem (and the flood protection it provides) on the outer coast. But Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 showed that New Orleans also needed better closer-in defenses for the flooding and storm surges that could occur in hurricane season in any following year. Enter the Army Corps of Engineers’ Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS). The $15 billion hurricane risk reduction system is a 133-mile perimeter around New Orleans, plus 70 miles of interior risk reduction structures, designed to defend the city from a 100-year level of storm surge. It contains assets including the largest surge barrier in the world – a 1.8-mile, 26-foot wall through Lake Borgne – and the biggest pump station in the world, the West Closure Complex on the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway.

The perimeter system was modified, strengthened and built in just five years, about 20 years sooner than this scale of project would normally be constructed. This happened because of two special arrangements: full, upfront funding from Congress, and special environmental compliance alternatives provided by the White House. Some of the projects were even designed and constructed at the same time. Even though many of the projects in the system are still under construction or otherwise incomplete, the 100- year flood risk reduction goal for the entire city was achieved by the hurricane season of 2011.

The scale of infrastructure involved in creating a perimeter floodwall to reduce risk to an entire city is staggering, as is its cost. But New Orleans, which is experiencing the fastest rate of land subsidence in Louisiana, did not have enough time to consider other options. A heavily engineered system of pumps, dikes, levees, floodwalls and more is now one of its most important assets, even as it ominously relies upon some of the same tools whose prior use (and failures) increased New Orleans’ vulnerability and devastation. The Bay Area and other coastal urban regions have perhaps more time to protect ourselves from flooding with multi-benefit tools like living shorelines, horizontal levees and waterfront placemaking projects. Meanwhile we can be sure that expensive and heavy armoring could be part of that toolbox, especially for emergencies, and especially if we wait too long to craft a better approach.

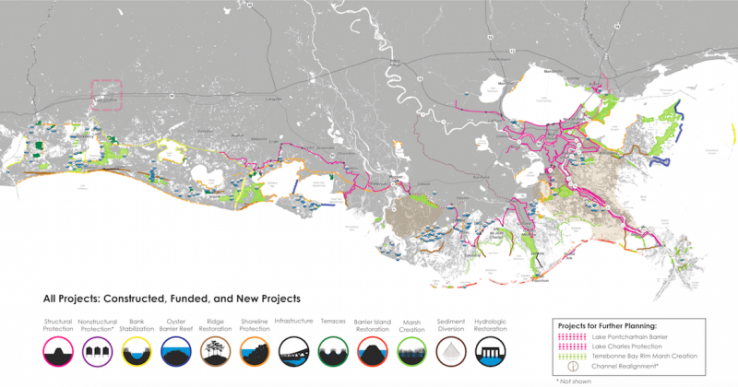

A master plan for restoration and reversing land loss

Louisiana's Coastal Master Plan includes a variety of over 300 projects that will reduce flood damages by up to $18 billion annually once completed.

3. The New Orleans Urban Water Plan: Living with Water in the Urban Landscape

Even with the risk reduction system in place, New Orleans, like many other coastal cities, has old water infrastructure, must manage significant rainfall even today, and faces an uncertain water future due to climate change. Meanwhile, its current approach to “interior” water management – or capturing, treating and pushing out the 60 inches of rain it receives annually – is failing in multiple ways. First, flooding is still very common during rain events: Some people in New Orleans talk about having to move their car to higher ground every time it rains, some properties suffer repetitive loss, and many people are inconvenienced due to street closures and transit interruptions. Second, last century’s flooding solutions — a network of pipes, pumps, canals and catch basins — are brittle and overwhelmed, and are themselves partly responsible for their own susceptibility to collapse. Third, land subsidence caused by constant pumping of groundwater and rainwater causes sinkholes, breaks water and wastewater infrastructure (and roads), and increases the amount of land area vulnerable to flooding.

In 2006, a collaboration between the regional economic development organization Greater New Orleans Inc., Waggonner & Ball Architects, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, and the State of Louisiana’s Office of Community Development Disaster Recovery Unit produced research and discussions to advance a different way. This would result in the 2010 Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, a 50 year integrated water management plan for three parishes in the region. The plan, conceived as a “third line of defense” behind coastal wetlands and the hurricane risk reduction system, aimed to manage water internally by delaying stormwater conveyance, storing stormwater in the landscape by retrofitting canals and building new ponds, and using stormwater management as a placemaking, neighborhood- connecting tool. This would have the benefit of retaining some buoyance in the soils, better utilizing rather than wasting water resources, and reducing unwanted flooding. Projects in the plan aimed to avoid $10.8 billion in flooding and insurance costs over 50 years, and generate $11 billion in economic impact, including up to 100,000 new jobs.

Gaining acceptance of a new paradigm — holding and circulating more water in the landscape — would require a cultural leap. For many New Orleanians, especially those with longer memories, water is viewed as a menace which causes floods and harbors mosquitoes (and in the past, malaria and yellow fever). To carefully show how these concerns could be eliminated by design, the plan proposed several demonstration projects to prove the viability of its concepts. These projects include a city block-size water garden, flooding an old canal (on purpose), floating streets (storing water beneath them), a “blueway” circulating surface water alongside an existing park and greenway, and a bioswale corridor to store stormwater. Collectively, these elements look to reframe New Orleans as a “water city” – like Amsterdam, Venice, or Suzhou — where the defining element of the regional geography finds expression in urban space and identity.

The Urban Water Plan is an opportunity for a paradigm shift beyond New Orleans and an opportunity for New Orleans to export its ideas to other regions. All coastal cities will need to learn how to live with water differently as the climate changes. In California, we’ll continue to experience the irony of more drought alongside sea level rise. In New York, the city will experience more severe coastal storm surges like those of Hurricane Sandy. The innovation of New Orleans’ approach is in drawing on its own historical geography and the tools of urban design to build resiliency, restore the environment and build a better city for everyone. Better placemaking does not have to be at odds with water engineering, unless you start too late. That idea is one the Bay Area should plan to import.

Observations on Resilience

The New Orleans region is like a postcard from the future to the Bay Area and other coastal regions. It is inscribed with both a dire warning against inaction and a set of opportunities and observations on what we could do before land loss, sea level rise and catastrophic flooding threaten our existence, too. Some of SPUR’s takeaways from New Orleans include:

A) Planning for resiliency and adaptation must take place at multiple geographic scales, providing multiple lines of defense.For example, where New Orleans is shoring up its Gulf coastline, city perimeter and interior drainage through engineered interventions both large and small, so can we plan to adapt on our Pacific coastline, along the Bay shore and within cities and neighborhoods. This would reduce our future flood risk through interlocking lines of defense which work together as a system — even if they aren’t explicitly planned that way — and can even benefit the environment through restorative approaches.

B) A science-based approach to planning can help set priorities and de-politicize the planning process. In developing the Coastal Master Plan, the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority built a rigorous model to evaluate over 400 projects and determine optimal sets of interventions to stem land loss on the Gulf coast. Although money to implement the plan must be authorized by the state legislature every year — a political process — the plan and the outcomes it promises are largely unassailable. To not accept its key findings and recommendations is to devalue the future of one of Louisiana’s biggest economic assets, and a region’s way of life. By focusing on saving a place rather than on improving the environment or doing something about climate change, the Master Plan and CPRA improved their chances for success, especially in Louisiana.

C) Historic levels of engineering and re-engineering will be needed to protect ourselves from climate change. We can’t solve this problem with small and incremental tweaks. We will need large-scale public action and interventions, like New Orleans’ near- complete Hurricane and Storm Damage and Risk Reduction System.

From certain points of view, it may seem irrational to spend billions of dollars to preserve places like New Orleans that are exposed to serious and worsening hazards, and certainly this should not happen everywhere. But our cities are about more than reliable service delivery. They represent an irreplaceable cultural patrimony. Like the coastal defenses under construction around the Venice Lagoon — and ultimately, we might reasonably assume, San Francisco — the protection of New Orleans is an investment in history and heritage that is hard to capture through a cost-benefit or sustainability lens.

The New Orleans Urban Water Plan vision for the Monticello canal (before and after above), includes widening the channel, and incorporating levees into a redesigned and agricultural and recreational open space that makes room for storm water and reduces unwanted flooding. Source: Greater New Orleans Water Plan.

D) Infrastructure can make better places by providing contributions to the landscape instead of detracting from it. New Orleans offers many reasons to be skeptical of infrastructure and engineering, but these can also make useful and beautiful contributions to the landscape. Great works of infrastructural art like the Golden Gate Bridge or the Hoover Dam are rare. But networks of smaller elements, like the canals of Venice or Amsterdam, the streets and squares of Savannah, or the stairs of San Francisco remind us that we can solve practical problems with a deep attentiveness to the human texture of the city. The New Orleans Urban Water Plan is an enticing case in point that we are interested to see develop over the next decade.

E) For better or worse, we are hurtling into climate change with no one in charge. Like New Orleans, the Bay Area has a governance challenge, including a large set of overlapping jurisdictions and public institutions. Dozens of flood control districts, sewer districts, water supply utilities, municipalities, ports, etc. are each developing their own projects and plans. This does not seem like an ideal arrangement to solve big collective action problems like climate change. These entities will interact with regional, state and federal agencies engaged in layers of planning, funding and building. Like it or not, this is how things are in the United States: We don’t have powerful, centralized public agencies that can assess the available science and act in the regional or national public interest. But, as with the multiple lines of defense in New Orleans, a degree of resiliency and innovation may emerge from multiple actors working at different scales, provided there is enough coordination to avoid unforeseen vulnerabilities.

F) Large areas of the Bay Area – including major parts of Silicon Valley – are low-lying and vulnerable to coastal flooding. Like New Orleans, the South Bay is a coastal area in ways that are not always apparent. The bay is subject to storm surges and lacks a comprehensive protection system. As sea levels rise and storms worsen, areas like the 101 corridor — reclaimed from the bay just a few decades ago but lacking a sense of being “coastal” — may be exposed to serious flooding with significant economic consequences. We would do well to act on what we know and invest in resilience today.

The San Francisco Bay Area has thus far been spared climate-driven disasters, but has styled itself as a leader in progressive policy and planning. In contrast, the impressive program of adaptation in New Orleans and southeast Louisiana are born not of ambition, but of crisis. In a bright red state with a petroleum economy, answers to sea level rise are being developed. In a poor city famous for neglect and corruption, a leading edge, people-centered approach to water management is taking shape. Although the solutions are imperfect and incomplete, we can only hope that as the coming century’s crises present themselves, other regions prove as resourceful as the Big Easy.

Endnotes

[1]http://www.americaswetland.com/photos/article/Coastal_facts_sheet_03_27…