Having lost the battle for both political and economic dominance, the city of Vallejo instead grew up around the new navy yard at Mare Island and the terminus of a railroad to the Sacramento Valley. Soon after, the area as a whole began its transformation into a critical industrial base for the region. San Francisco’s growth and prosperity quickly pushed out the dirtiest and heaviest of its industry, and with southward expansion blocked by the wealthy denizens of the San Mateo hills, industry began moving to the East Bay. Oakland would develop as an independent industrial city in its own right, but industry along the Contra Costa shorelines was more directly tied to San Francisco capital, and by the 1890s the area became a niche for the type of dirty industry unwanted elsewhere: refineries, gunpowder manufacturers and glue factories. The next hundred years saw the growth of canneries, paper mills and chemical plants, not to mention the fiberboard factories, steel mills and oil refineries that would feed the suburban boom throughout the Bay Area. These historic towns would be transformed into small industrial cities with historic downtown cores of Victorian and Craftsman houses, train and ferry depots and all the trappings of civic life in small California cities, albeit with more of a “company town” feel than was common in other parts of the Bay Area. [3]

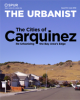

World War II brought diversity, population growth and even more heavy industry, as Vallejo’s Mare Island and Pittsburg’s Camp Stoneman grew on either side of the strait. Even as deindustrialization began taking its toll in the 1970s, industry remained critical to the employment base and culture of the region; all four of the Bay Area’s major oil refineries dot the Carquinez coast from Richmond to Benicia. Today, the 25 power plants in the Cities of Carquinez alone (combined pop. 642,697) account for half the power produced in the Bay Area (pop. 7,150,739).

In the past three decades, the Cities of Carquinez have embraced massive suburban growth, as the cities and counties responded to the heady mix of deindustrialization and the effects of Proposition 13. Incessant demand from both developers and prospective homeowners led to subdivision after subdivision, more than doubling the area’s population between 1980 and 2010.4 Environmentalists and smart growth advocates fought the expansion, an approach that succeeded in preserving key stretches of marshland and open space while failing to prevent the bigger pattern of sprawling urbanization.

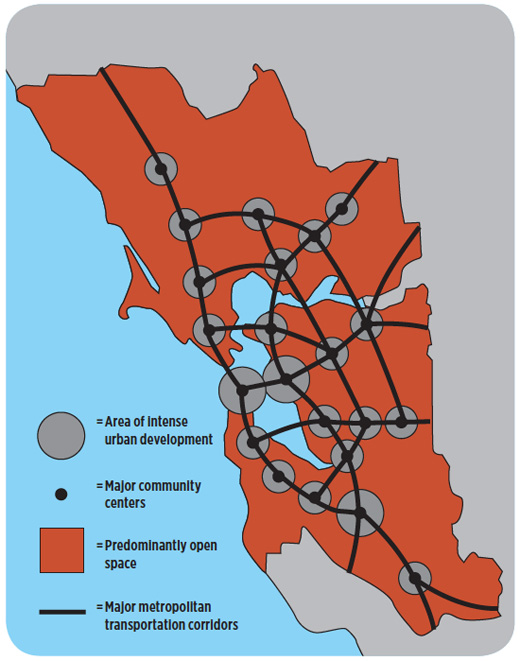

Figure 2

City-Centered Bay Region Schematic Design Concept 1970 1970 ABAG Regional Plan

From the 1950s through the 1970s, Bay Area regional planners considered the historic downtowns of the Cities of Carquinez as important places to concentrate future growth in a way that did not perpetuate the auto-oriented suburban pattern, which even then was a problem. This graphic identifies four distinct subcenters in the Cities of Carquinez around Antioch/Pittsburg, Vallejo, Fairfield and Vacaville. In 1970, city-centered did not mean only in the three central cities.

This emphasis would continue through the 1970s, in eastern Contra Costa County in particular, which had greater potential for connection to the San Francisco and Oakland core than the Solano County cities, by virtue of the BART plan. In a long-forgotten 1971–72 plan for eastern Contra Costa, a massive multidisciplinary team from UC Berkeley argued that an “adequate intercity transportation system between Pittsburg and Antioch, supported by some form of inter-metropolitan transit, could have a profound effect upon the future development pattern and resultant urban form of these two cities.”[5]

The most profound vision for a city-centered eastern Contra Costa County came in the 1976 Pittsburg- Antioch BART Extension Plan written by Parsons Brinckerhoff. In detailed renderings of downtown Antioch and Pittsburg, planners articulated a vision of growth for the area that would establish it as a new subcenter of a growing region. It was a vision of a place far more urban than Lafayette and Orinda and not too different from the urban corridors of BART’s Fremont line, rather than what it became — a bedroom community extending deep into the hillsides and far into the Central Valley.

Yet in this very plan one can see the seeds of its own undoing. Not only did BART planners see eastern Contra Costa County as an area where they could “direct growth rather than merely respond to growth,” they also assumed that “without major regional policy changes concerning highway funding and environmental acceptance, the corridor without a BART extension would most likely experience a limited level of growth.” The notion that planners could prevent growth by eliminating “growth-inducing” infrastructure became dominant following the postwar suburbanization wave, when housing so clearly followed federal highway dollars.

What the rebellion against “growth-inducing” infrastructure did succeed in doing was to help end any hopes of a BART extension to eastern Contra Costa County. BART would not arrive in Pittsburg/Bay Point until 1995, and the route for eBART (a new smaller, diesel version of BART), scheduled to open in part in 2015, goes down the freeway median, not through the historic downtowns. Highway funding would not come for two decades, but the region grew anyway. And it grew in precisely the way that planners a half century ago had already tried to avoid: Their lack of growth-inducing infrastructure had not slowed growth but caused it.

Many of the ideas in these plans arose during the early 1960s heyday of regional planning in the Bay Area, when nascent regional agencies like ABAG were buoyed by activists concerned with the mounting threat to the bay and by a cadre of academics at UC Berkeley whose influence would be felt nationwide: Catherine Bauer Wurster, T.J. Kent, Mel Scott, Mel Webber and James Vance, to name a few.

Yet we would do better to remember the geography of these plans rather than revive any hopes for a magical regional agency. The Bay Area has always had multiple centers — what James Vance called a “collection of realms” — and during the early 1960s, our regional plans not only expressed a vision of smart growth in these areas but also resulted in dedicated subregional plans that have never been replicated. Heading into the 1970s, regional leaders largely turned their backs on the Cities of Carquinez while local leaders learned to fight the funding battles at the regional and state level, eking out money for highway expansions and eventually a BART extension. But the money came with little vision of a different urban future. Instead, we settled for a fragmented regime of mutually destructive battles, environmental lawsuits and endless subdivisions. When Caltrans refused to build a freeway to bypass the historic downtowns of eastern Contra Costa County and accommodate a quarter of a million residents with commute needs that were worsened by the lack of local jobs or transit, the cities got together to build their own freeway.

Moving Forward

Even if many Bay Area residents are not personally familiar with much beyond the freeways of Carquinez, those of us who follow planning and development have seen the headlines about Vallejo’s fiscal problems or the struggles in many of these communities with foreclosure and stagnating property values. As Jake Wegmann and Chris Schildt show quite clearly in the next article, the challenges facing these cities are very real.

What is also clear is that these communities are integral to the Bay Area not simply because of their history but because of who moved there. An entire generation of the most diverse middle-and workingclass residents in the Bay Area’s history made the Cities of Carquinez home, attracted by the very same suburban dream that anchors so much of the region but has long been unaffordable to most of us. There is a sad irony to the fact that people of color are bearing the brunt of the challenges facing the Cities of Carquinez. Our collective inability to realize many of the plans from the 1950s and 1960s, plans that may have provided better connections to the core of the region and perhaps a less commute-dependent job base, stems in part from the collective reaction to the modernist planning of that generation, planning that was not only arrogant but racist. We rebelled against this type of top-down planning, working to make planning more democratic, more participatory and more inclusive. But along the way, we lost the ability to look into the future and declare that it would be different from the past.

Taking action in this area will not be easy, but bold new ideas are possible if we take a long-term approach. The region as a whole needs to rethink what smart growth means. This region is an area with “good bones” that can accommodate growth: historic, waterfront downtowns; underutilized rail networks; ferry and BART service (which has been planned but whose implementation is lagging); and ample industrial land. It also has an excellent geography if one thinks “megaregionally”6 — Carquinez may be far from the Bay Area’s core, but it is well placed between the growing Sacramento region and the Bay Area, an important node in a multipolar region. Greater Carquinez is also home to two of the region’s major military base redevelopment projects, Vallejo’s Mare Island and the Concord Naval Weapons Station, which will have major educational institutions alongside housing and jobs. If done right, these two projects alone could alleviate some of the issues with local jobs and transit-accessible higher education and provide valuable new centers of industry and innovation to a growing region.

Taking steps in this direction requires a true longterm subregional plan, a process that will engage local and regional institutions and produce a collective vision strong enough to sustain confidence in the future — confidence from homeowners, from investors, from funders and higher levels of government, from voters and elected officials. Achieving and implementing this plan will require that leaders of these communities work to build a new subregional coalition that can work with regional and state actors simultaneously on a vision for the area that puts an end to greenfield-centered development and finally realizes the city-centered possibilities of Carquinez, 150 years in the making.

With this type of planning, the Cities of Carquinez could potentially play a major role in the future of fiscal and developmental policy far beyond the strait. The Bay Area must consider long-overdue ideas such as tax-base sharing, and subregions like Carquinez may be prepared to take steps other parts of the region fear. As California ultimately considers redevelopment 2.0, there is no reason why the Cities of Carquinez, in partnership with a newly engaged region, cannot be a site of experimentation and innovation in how we build and rebuild our cities. These communities must be seen as a key center of the Bay Area’s future, a representation of much of what we have done wrong and much of what we can still do.

---

[1] Mel Scott, The San Francisco Bay Area: A Metropolis in Perspective (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1959).

[3] Richard A. Walker, “Industry Builds Out the City: The Suburbanization of Manufacturing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850–1940, in Robert D. Lewis (ed.), Manufacturing Suburbs: Building Work and Home on the Metropolitan Fringe (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004).

[4] See "Diversity Didn't Cause the Foreclosure Crisis," p. 10, for detailed demographic data.

[5] “Pittsburg & Antioch, East Contra Costa County Present And Future Directions (1972–1982),” Report of a Study Organized and Conducted by a Multidisciplinary Student Team at the University of California, Berkeley in the Academic Year 1971–72.

[6] Gabriel Metcalf and Egon Terplan, “The Northern California Megaregion,” The Urbanist,November/December 2007.