First the bad news: City revenues are falling, costs for the health and pension benefits of retired public employees are exploding, and experts disagree on whether an end to the current recession is anywhere in sight. The City is embarking on its fourth consecutive budget process requiring reductions of nearly half a billion dollars per year. As if this weren't enough, Governor Jerry Brown's proposals for the state budget could dramatically change the very relationship between state and local governments, shifting services (and costs) to the counties and cities.

And the good news? What has begun as a national recession may have triggered a rare moment of opportunity to deal with the causes of our structural deficit. There is an opportunity to correct past mistakes, reinforce core services and to put San Francisco back on the right path.

It is time for everyone to acknowledge that it is not merely the national recession that has caused our current budget crisis and reduced funding for city services. Instead, both falling revenues and escalating costs lie at the root of this budget crisis. We cannot afford the government we have. It is not sufficient to merely balance costs and revenues for one fiscal year. Rather, we must change the core structure of our City budget.

Decreasing revenues, increasing costs

The recent recession has had an enormous negative impact on City revenues. Sales tax receipts are down more than 10 percent since 2008. Business taxes have declined more than 8 percent since 2008. Hotel tax revenues—a bellwether for tourist activity and other business activity—are down more than 10 percent since 2008. Property tax revenues are projected to be down by nearly 4 percent for fiscal year 2010-11, the first decline this decade in a revenue source that has grown more than 120 percent since 2001.

As if this perfect storm were not enough, the financial challenges of the state have repeatedly affected City funding in recent years. While a number of one-time solutions and borrowing have been used to bridge the state deficit—including federal stimulus funds, redirection of funds designated for local public transportation, and widespread worker furloughs—more recent discussions have centered on permanent, structural changes such as eliminating local redevelopment agencies.

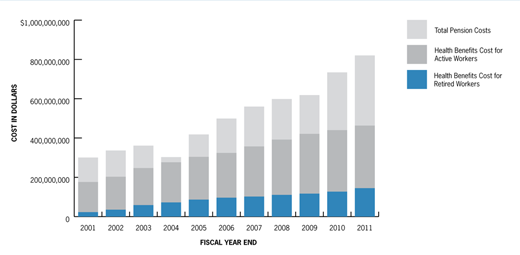

While some of these revenues may soon recover to previous levels, any gains would be virtually erased by the growing cost of retired public employees' health care and pension benefits the City is obliged to pay, now more than $820 million per year.1 Pension and health-care costs have escalated more than 172 percent in the past decade, and nearly 65 percent in the past five years alone. For years, the City's pension system reported that it was "over-funded" due to higher-than-projected investment returns, leading the City to underfund annual pension contributions. The money was then redirected to start or fund existing programs that everyone is now loath to eliminate. But the combination of a sudden and severe drop in asset values, longer life spans and modest pension increases has resulted in the City having to significantly increase annual payments to the pension plan.

Retiree health-care costs, meanwhile, continue to present a challenge for the City. San Francisco Proposition B (2008) created a two-tier structure for funding retiree health care. The current unfunded health-care liability (which includes all future payments for City employees and retirees) for the largest group of employees—those hired before January 9, 2009—currently sits at $4.3 billion and continues to be completely unfunded.2 These benefits are funded on a "pay as you go" basis, meaning that the cost of these benefits is paid as they come due each year.

Retiree health benefits for the second tier of employees—those hired after January 9, 2009—are prefunded through a combination of employee and employer contributions. Benefits for this group of employees are expected to be fully funded through these combined contributions and will not alter the unfunded liability for the other tier.

Since 2008, the Government Accounting Standards Board—an independent organization on which state and local governments rely to set accounting and reporting practices—has required municipal governments to report the costs of their health-care benefits for retired employees, but does not require funding for these future costs. Pensions must be reported under a separate requirement. While the City began reporting these liabilities in 2008, actual health-care costs have been climbing for quite some time. Health-care costs for current and retired employees combined have increased 147 percent over the last decade—and nearly 43 percent just in the past five years. Meanwhile the number of City employees has declined morethan six percent since 2001.3 The combined cost of all employee benefits has risen from $408 million in FY 2000-01 to $978 million in FY 2010-11. We need to begin driving these costs down to sustainable levels while being sensitive to the fact that City employees have already agreed to wage concessions multiple times in the last ten years.

In November 2010, SPUR gave its reluctant endorsement to a pension reform measure, Proposition B. SPUR's support was ambivalent because the measure had some serious downsides, but nevertheless we believed that something like Prop. B was necessary to begin getting costs under control. Prop. B would have saved the City around $120 million per year starting in fiscal year 2013-14 by increasing the contribution required from employees toward the cost of their pension and health care. It was defeated at the ballot, sending all of us back to the drawing board for reform ideas. SPUR pledged to be more proactive in coming up with solutions this time around and, indeed, that is one of my major responsibilities this year as SPUR's good government policy director.

We are talking to anyone who will listen, from labor leaders to advocates for public services. We are open to many kinds of solutions, as we think everyone should be. There is more than one way to reform San Francisco's pension and health-care systems, and it is very important to us to find a way that feels as fair as possible to City workers. Some big ideas are in circulation:

1. For higher-paid City employees, create a mix of "defined benefit" and "defined contribution" pension plans. The idea here is that the taxpayers would give City workers a traditional public sector guaranteed pension up to some dollar amount: say, $100,000 in salary. Above that amount, the pension would switch to something more like what non-profits and businesses give—a program in which the City contributes to employee retirement plans, with incentives for employees to contribute to their own plans as well.

2. Raise the retirement age to 65 to match the age when Medicare kicks in. City public-safety employees now can retire as early as age 55, and all other City employees can retire at age 62. But modern life expectancy projections predict that retirees will collect their benefits for many years, and projections for pension fund earnings suggest that earnings will not keep pace with benefit obligations. A compounding factor is that younger retirees represent greater health-care costs for the City because these retirees are not yet eligible for Medicare. Gradually raising the retirement age for full benefits to 65 for employees not in the public- safety field would do a lot to reduce the costs of retiree health care while also recognizing that most people continue to lead active, productive lives past that point.

3. Establish a cap on the amount of salary that can be used to calculate pension earnings. The IRS caps maximum pension earnings at $245,000 a year. Proposals include reducing that limit to $200,000 or $135,000.

4. Increase baseline pension determination to average either three or five years of earnings and mitigate effects of "pension spiking." In pension spiking, an employee boosts his or her earnings by some combination of promotion, special pay, and other retention or training incentives that inflate pension earnings. These increases artificially inflate employee earnings for the final years of employment. But because pension benefits are calculated based on the employee's earnings in this period, this also boosts the benefits the City must pay for the entire duration that former employee receives a City pension. Increasing the period over which earnings are averaged—and pension benefits determined—will help to provide a more accurate reflection of earnings. A related reform would be to limit the categories of earnings included in baseline benefit calculation to base pay, rather than including overtime, comp time and bonus pay.

5. Increase pension contributions of public- safety employees or modify their pension formula to more closely match other City employees. Police officers and firefighters may retire at 55 and collect 90 percent of their final-year earnings. Other City employees have a higher retirement age and lower benefits: 75 percent at 62 years. There is room to recognize the special contributions and risks that public-safety employees make, while still ratcheting down these benefits somewhat in the interest of fairness and the long-term financial viability of the pension system.

There are a number of legal questions related to making changes to benefit plans for current employees and retirees. All of these complex problems require thoughtful well-analyzed solutions, which SPUR wants to facilitate and support.

The way forward

The good news is that the City has a robust finance and accounting operation as well as an active audit and management-review function, and it consistently receives awards for exemplary performance in financial and performance reporting. In recent years the City has analyzed and provided valuable recommendations on a variety of topics that could yield dramatic impact—including analyses of public transportation, the management of City relationships with nonprofit service providers, and ways to improve the provision of police services. In many ways this provides an excellent foundation on which to build and strengthen the City organization.

What else can the City do to better prepare for the future?

1. Confront the cost of known, unfunded liabilities. Bringing out all known liabilities is an important first step to truly balance the budget. The City's retiree health-care liability was largely unknown and unreported until required by the Government Accounting Standards Board. Enumerating the $4.3 billion liability has enabled a meaningful public discourse about how to address retirement-related liabilities, and how to limit the impact of ongoing pension responsibilities without jeopardizing high-priority services.

2. Reinforce financial stability via long-term planning. Thanks to Proposition A (2009), a budget reform measure, the City is in the process of defining a five-year financial plan that will help to clarify program needs and available revenue sources. Multiyear budgeting helps to identify long-term structural budget problems early so they can be addressed in the process. On the revenue side, many agencies already are actively investigating revenue opportunities that can supplement existing funds or replace those that have disappeared.

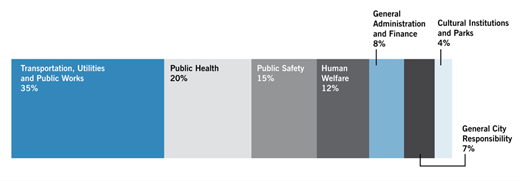

3. Aggressively pursue revenue diversification strategies. Given the heavy subsidies many departments receive from the City's General Fund—of which more than 20 percent in turn consists of federal and state subsidies —the current trends of declining federal and state funding indicate that diversification of departments' funding sources would be extremely beneficial. Some departments will have the opportunity to generate revenue to keep up service levels through philanthropy, fees for service or other creative methods. This won't be an across-the-board solution, but if used carefully and selectively it could benefit some departments that directly interact with the public.

4. Define measurable outcomes for City services. While many City programs carry with them an implicit understanding of their goals, being able to measure the outcome of programs is critical for general oversight and accountability. Though not all outcomes lend themselves readily to measurement, there must be some means by which to gauge whether programs are working. Arguably, the most critical component of determining a program budget should be how much funding is required to achieve the program objectives. The City should develop explicit prioritization for programs whose outcomes can be measured.

5. Define program priorities to balance the budget rather than simply imposing across-the-board cuts. The easy way out of an imbalance between income and expenses is to cut all functions equally, but almost always the better way is to make some explicit decisions about where to invest and where to cut. This is, of course, easier said than done in a public budgeting process.

6. Develop a long-term labor strategy that results in more balanced negotiations. Over and over, the City has agreed to wages and benefits that it may or may not be able to afford, only to subsequently be confronted with an economic downturn that makes negotiated labor contracts untenable. Over the last decade, the City has on multiple occasions had to implement workforce reductions and re-open contracts to ask City employees to "give back" some amount of wages or benefits. This is terrible for morale, as well as budget planning. While it is true that public-sector unions may often negotiate with elected officials who have little incentive to strike a "hard bargain," the City cannot keep making deals that are financially unsustainable. There needs to be a way of moving the labor-management culture into more of a shared problem-solving effort, perhaps similar to the spirit in which union leaders and senior City management are now working on solutions to pension and health costs.

Taken independently, these principles have the potential to better prepare and position the City for success, whether conditions improve or finances remain constrained. In fact, they can help the City to expand its capacity through collaboration rather than through additional employees. Together, these have the potential to improve services, program effectiveness and access through a combination of improved transparency, service capacity and operational focus. We must confront these challenges in a way that reinforces our priorities and strengthens the services in a sustainable way.

Endnotes

- San Francisco Controller's Office reports: City and County of San Francisco Employee Benefits, Executive Information System extract of Financial Accounting and Management Information System data (Feb. 17, 2011); FY 2010-11 Six-Month Budget Status Report (Feb. 9, 2011); Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports, FY 2000-2010.

- Memorandum to Mayor Gavin Newsom from Con troller Ben Rosenfield, Dec. 15, 2010: "Report on Retiree (Postemploy ment) Medical Benefit Costs."

- San Francisco Controller's Office reports: City and County of San Francisco Employee Benefits, Executive Information System extract of Financial Accounting and Management Information System data (Feb. 17, 2011).