We can credit William Howard Taft for giving San Francisco the title of “The City That Knows How,” and in reality San Franciscans usually get what the city planners have up their sleeves. In 1902 they made a law — no more burials within city limits, followed by an even more restrictive law in 1910 — no more cremations. An additional requirement was that all graves be dug up and relocated to the tiny town of Colma. You may hear other stories, but the accepted rationale was that the city only had 49 square miles and needed every bit for more profitable (and taxable) ventures.

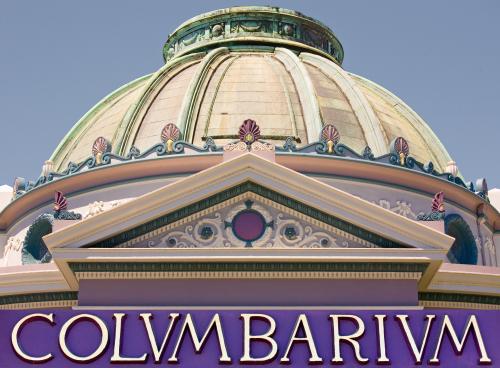

After completing the arduous task of moving thousands of bodies, the 27 acres of the original Odd Fellows Cemetery was quickly replaced with streets and housing. But the Columbarium, an imposing and solidly built repository-of-ashes, still stood at the end of Loraine Court. Seemingly a bit out of place in the center of progress, the Columbarium survived a City Hall skirmish to achieve landmark status in 1995, and it and its 7,000 “residents” remain.

The building’s name was taken from Latin: "columbarium" originally meant a place to keep pigeons. You'd think they would have come up with something a bit more human.

Located off the beaten path, not far from San Francisco University, the Columbarium is probably a place many residents don't know about. The Neptune Society, and the site’s sole (and tireless) caretaker, Emmitt Watson, have brought the place back to life. If you are interested, space is still available.

Where do we put our dead? We design our cities in preparation for the future, but concern about where to put the dead doesn't seem to be a priority. We deal with it in the shortest amount of time possible, yet nothing is more long-lasting. Making death a cohesive and compatible part of life will likely aid our acceptance of the inevitable.

An imposing structure. The four-tiered, round concrete building was designed by British architect Bernard J. Cahill in 1897. Previously, Cahill had gained a reputation for designing San Francisco's Civic Center. The building is the common blend of Roman and Greek architecture, with an imposing and heavy exterior, but the inside is much more light and airy.

A peaceful place with lovely objects. I'm not exactly sure what I was expecting, but the first time I entered the Columbarium my jaw dropped. Rich golden light filters in through stained glass windows, bathing the interior and precious objects in warmth. I first learned of the site from a portrait series shot here by San Francisco photographer Julie Michelle. It struck me as quite odd that someone would want to be photographed inside such a place, but after fully absorbing the mood I think this location made perfect sense.

We can thank Mr. Watson. The Columbarium hasn't always been this inviting. It had fallen into a deplorable condition prior to 1980 when it was purchased by the Neptune Society. The roof and everything else leaked, and squirrels and raccoons were making the place their own. Singlehandedly, Emmitt Watson has made the Columbarium his life's work, pouring his blood, sweat and tears into its restoration over the past 30 years.

They say you can't take it with you. Many crypts are filled with meaningful and often whimsical objects from the person's life. It's not difficult to see that this individual was into photography and boating — hobbies he financed with his profession as a dentist.time.

Death disguised. Another well-illuminated crypt filled with personal objects. Some of these are so intimate that the discovery process almost feels like snooping. Emmitt Watson says, “What makes this place special is that people come here and they're comfortable. After services here, they don't run away. They take time, look around the building, enjoy it. There's a difference here from a regular cemetery — this is death disguised. I'm in here all the time and I forget that death is all around me.”

Somber and reserved? A repository-of-ashes is not your typical place to hear laughter, but here at the Columbarium you probably will. This is San Francisco and we, like Mr. Fernando here, are all highly quirky individuals in one way or another. And we know how to have a good time.

Final resting spot. Before my first visit someone had told me that Harvey Milk's ashes were here at the Columbarium, and although I searched high and low, it was only when I was leaving that I finally found his crypt near the front entrance. His crypt contains only a simple display of his portrait — my delightful afternoon suddenly turned into one of sadness.