This article is the third in a three-part series examining San Francisco’s increasing structural deficit and the difficult decisions required to close it. Part 1 looked at the budget process. Part 2 outlined the growth of San Francisco’s revenues and expenditures.

San Francisco is facing a fiscal crisis unlike any in its history. While economic downturns and budget shortfalls are not new to the city, the current budget deficit is different — it’s the result of structural imbalances and the reality that a return to the city’s previous revenue growth rate has not, and likely will not, materialize. The city is now at a pivotal moment — a moment that requires difficult, deliberate choices to restore structural balance.

The Illusion of Endless Growth

Between 2010 and 2020, San Francisco experienced extraordinary growth. Its economy surged, driven by a booming tech industry and a strong real estate market. The city’s budget expanded in tandem, growing from $6.6 billion in FY 2009–10 to $12.3 billion by FY 2019–20, an 86% increase. By comparison, cities like Los Angeles and San Diego saw budget growth of only 52% and 48%, respectively, during the same period.

This rapid budget expansion, however, masked rising fixed costs. Even before the pandemic, many municipalities were struggling to keep up with these costs, and San Francisco was no exception. Revenue growth was already beginning to lag behind long-term pension obligations and health care and insurance costs when the pandemic hit.

The Pandemic’s Seismic Shock and the Short-Term Fixes

COVID-19 upended the local economy. In just two months, San Francisco’s unemployment rate skyrocketed from 2.2% to 13%. More than 115,000 jobs were lost, and the city faced its largest fiscal deficit in history. Tax revenues plummeted everywhere, and in response, the federal government stepped in with funding to support cities with their response and recovery efforts.

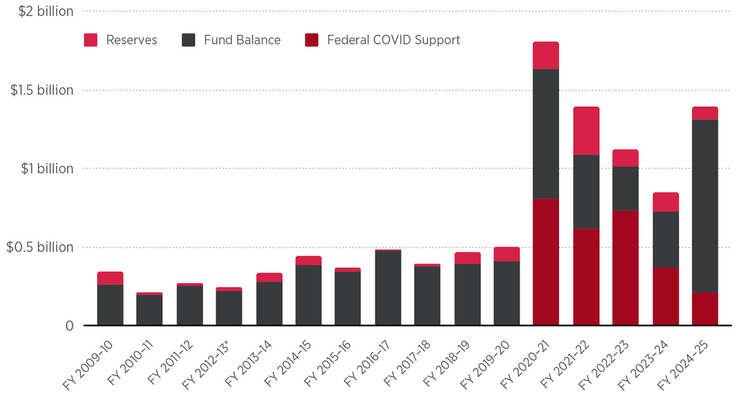

Over the past four years, the city has relied heavily on federal COVID relief funds such as the American Rescue Plan Act, which provided $624.8 million in direct aid. Additional funding came through the CARES Act and federal transit support. The city also dipped into its reserves, reducing them by 27%, and it relied on unspent money and prior-year savings — referred to as “fund balance” — to close its deficits.

Now-Expired Federal Covid Relief Funds Helped Keep the City Fiscally Afloat

The city has also had to tap its reserves and rely on unspent money and prior-year savings — referred to as “fund balance” — to close its deficits.

Source: SPUR analysis of Data SF “Budget” dataset.

These strategies helped San Francisco survive the immediate crisis, but they were temporary fixes intended to carry the city to an economic rebound that has not happened. The city used one-time revenue sources to pay for on-going expenses, and those expenses grew as the city and county worked to meet the community’s increased needs during that period. Now, most of those temporary sources have run dry, and revenues haven’t returned to pre-pandemic levels. Meanwhile, the expanded budget remains and is growing.

A Widening Fiscal Gap

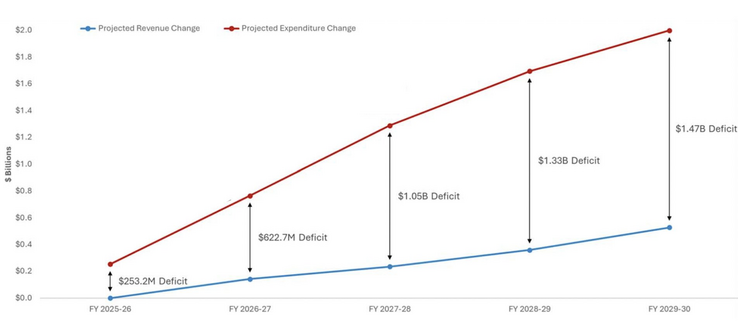

San Francisco’s financial picture is increasingly grim. With reserves diminished, and COVID-era support now expired, the city is projected to face a $1.47 billion General Fund deficit by FY 2029–2030. This deficit doesn’t factor in the threat of additional proposed cuts to state and federal funding, which if realized could upend social service delivery in San Francisco. The imbalance between revenues and expenditures is widening fast, driven by slowing revenues and rising fixed costs that are impacting city contracts and employee costs.

Expenditure Growth Is Projected to Far Surpass Revenue Growth Over the Next Five Years

At $1.7 billion, revenue growth is projected to be more than triple revenue growth, $520 million, by 2030.

Source: Fiscal Outlook and Department Budget Instructions, December 2024.

Several economic forces are dragging down tax revenue: a weak real estate market, reduced business travel, declining retail sales, and fewer people downtown due to the shift to hybrid work. Meanwhile, the city’s population has declined as its budget has continued to grow.

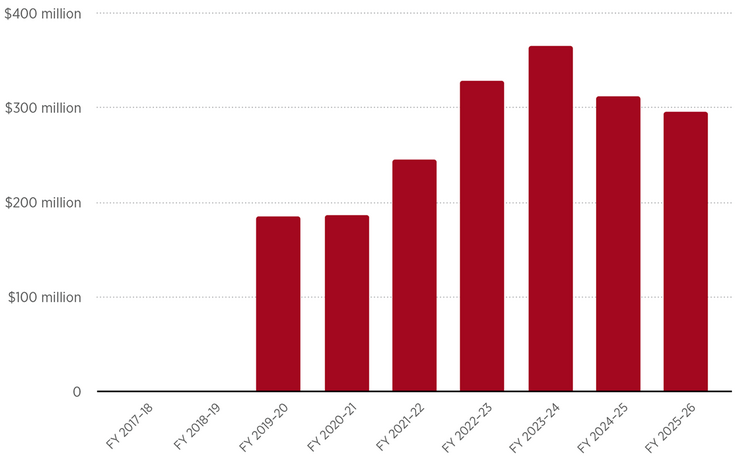

Compounding the problem, San Francisco relies on increasingly vulnerable state and federal funds to balance its budget. About 20% of the city’s budget is made up of state and federal funding. Threats to federal funding sources that support public health, child support services, and emergency management could further increase the deficit if cut. In addition, proposed changes to California’s Cap-and-Trade Program could decimate the city’s transportation budget. Furthermore, San Francisco has become increasingly reliant on Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund dollars — surplus property tax funds that the state returns to some California counties when minimum local school funding needs have been met. The state can eliminate this practice at any time, and Governor Newsom proposed curtailing this revenue in the FY 2024–25 budget, though the legislature ultimately rejected the idea. Future attempts to keep Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund dollars at the state level are likely as the state experiences budget challenges of its own.

San Francisco Has Become Increasingly Reliant on Excess Dollars in the Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund

Surplus dollars in the fund are returned by the state to cities and counties, but the state can eliminate this practice at any time.

Source: SPUR analysis of Data SF “Budget” dataset.

Budget-Balancing Constraints

The city’s economic recovery has been slow and uncertain. While some indicators are improving, a return to the growth years of the 2010s is nowhere in sight. Federal relief is gone, reserves are low, costs are rising, and continued reliance on unstable revenue sources only postpones inevitable and painful decisions.

Balancing the budget in government is far more complicated than in the private sector. Government is tasked with providing services that are, by their very nature, not profitable. Unlike private sector companies, government must provide these services to everyone, without exception, in ways that are accessible, equitable, and fair — with increased demand during harder economic times. Every program has a constituency, and even small cuts can provoke significant opposition because someone, somewhere, fought hard for it to be in the budget in the first place and because programs often are meeting a real community need.

Like program cuts, layoffs are politically fraught. In addition, they are operationally difficult, constrained by complicated civil service rules geared to protect an employee’s seniority and promote fairness. Essentially, a laid-off worker can take the position of another employee who is less senior, effectively "bumping" them out of their job. Instead of the person in the eliminated position losing their job, a single layoff can trigger a chain reaction of employee displacements across the city. This complex process disrupts services, consumes considerable staff time and energy, and significantly impacts numerous employees and their teams. Because of the disruption they cause, as well as the additional expense they create once severance packages are factored in, layoffs are often considered a last resort.

Finally, as outlined in Part 2 of this article series, only about 18% of the budget is truly discretionary. Voter-approved baselines and set-aside mandates draw from the city’s discretionary revenues, further restricting options. Changing many of the rules and constraints related to the budget process, including set-asides, will require city charter reforms that voters must approve.

Structural Solutions

The process of developing the budget started many months ago, as outlined in Part 1 of this series. The mayor will propose a balanced budget by June 1, as required by the city’s charter. This budget will likely include a combination of solutions, some to achieve savings in the short term and others to chip away at the long-term structural deficit. The latter category includes the following solutions:

- Stop relying on one-time revenues and reserves. These funds have masked the city’s true financial condition for too long and increased San Francisco’s vulnerability to reduced state and federal funding.

- Develop and commit to a long-term financial plan. Building on its five-year financial plan, the city should identify measurable goals and actionable strategies to bring ongoing revenues in line with ongoing expenses.

- Implement permanent cost-cutting measures. Contracting and personnel costs must be reviewed and reduced. Across-the-board percentage cuts won’t be enough — labor agreements and contracts will need to specify targeted reductions to services and programs.

- Redefine and focus on core services. The city must ask what services are essential and ensure they are delivered efficiently and effectively. Rather than make broad cuts that degrade all city services, the city should scale back or eliminate nonessential programs.

- Strengthen budget management. The city’s fiscal offices, including the Mayor’s Budget Office, the Controller’s Office, and the Board of Supervisor’s budget and legislative analyst, should be resourced appropriately to shape and manage the budget.

- Increase coordination across the government. Overlapping departmental functions and bureaucratic inefficiencies hinder San Francisco’s ability to respond to fiscal and service delivery challenges. The City Administrator’s Office should be empowered by the mayor to serve as the city’s chief operating officer, a role focused on the city’s long-term projects and core operational functions. The city administrator should have the authority to convene departments, set direction, and manage performance across the city.

- Update the city charter and reduce voter-mandated funding restrictions. Many constraints that the city faces in closing the structural deficit will require thoughtful and holistic charter reform reflecting the complexity of the city’s service delivery system. This reform should be aimed at clarifying and refining the roles of key city officers and departments by reducing duplication where possible and updating rules that the city uses to manage its finances, workforce, and contracting to create more effective processes. Voter-mandated baselines and set-asides should be reviewed for revisions and potential sunsetting.

As SPUR reported in Designed to Serve, once something is created — be it a department, commission, board, advisory body, or piece of legislation — eliminating it can be difficult, even when it no longer serves the greater good of the city or the cost to maintain it exceeds the benefit. The mayor and the Board of Supervisors must be willing to make some people unhappy in order to protect and sustain services for the broader community.

A Pivotal Moment

San Francisco is no longer in a temporary downturn — it’s undergoing a fundamental reset. The choices made over the next few years will determine whether the city can build a stable and sustainable fiscal future or will continue bouncing from crisis to crisis.

Rebalancing the budget will require a foundational shift in how San Francisco manages its finances. That shift means ending reliance on one-time revenues, redefining core services, implementing permanent cost controls, and considering reforms to the city’s charter, labor agreements, and voter-approved measures to unlock greater flexibility. The path forward is politically and operationally difficult, and it will require city leaders to work together and demonstrate an immense amount of political will.

San Francisco can no longer rely on short-term fixes to patch over its deepening structural deficit. Structural problems require structural solutions. The city must act decisively — and quickly — before the window for manageable reform closes and the consequences of inaction become far more severe.