This article is the first in a three-part series examining San Francisco’s budget process, the growth of revenues and expenditures, and actions to address the increasing structural deficit. Part 2 looks at revenues and expenditures.

San Francisco’s most significant challenge in 2025 and the coming years will be balancing the city’s budget and addressing its underlying structural deficit. Key city priorities, including increasing housing supply, revitalizing downtown, maintaining transportation operations, and addressing homelessness, will remain difficult to tackle unless underlying budgetary issues are fundamentally resolved.

San Francisco’s expenditures have skyrocketed due to inflation and increased fixed costs related to wages, benefits, and retirement, but revenue growth has not kept pace. This challenge is not unique to San Francisco. Many U.S. cities are facing similar challenges, in part due to the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sluggish real estate markets; the shift to hybrid work that has reduced foot traffic and increased office vacancies in downtown centers; declines in business travel, tourism, and retail sales taxes; and other economic factors have dragged down local tax revenues.

From 2020 to 2024, San Francisco, along with many other cities and counties, used one-time pandemic relief funds such as American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds and reserves to backfill budget gaps spurred by the pandemic, but these funds have dried up, and revenues haven’t returned at the levels expected.

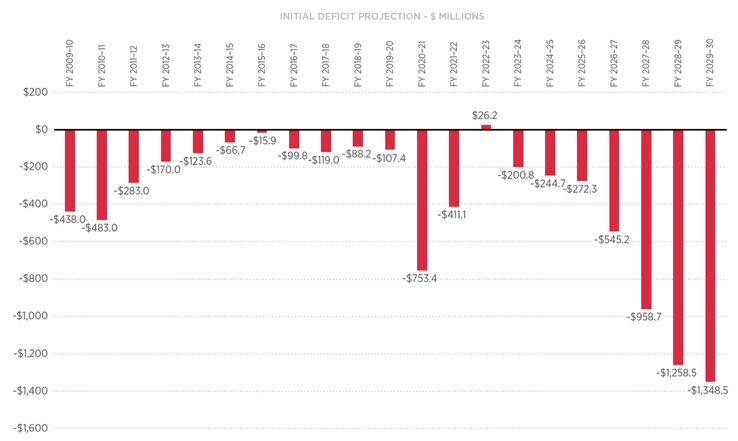

The City Controller’s Office anticipates a deficit of $817 million for fiscal years 2025–2026 and a nearly $1 billion deficit for fiscal years 2027–2028 — the largest expected deficit in the city’s history. Notably, these projections do not reflect the potential loss of funding that could result from cuts being proposed at the federal and state levels.

Without corrective action the city’s general fund deficit could grow to $1.47 billion by fiscal year 2029–2030

Over the next five years, the city’s revenue outlook is expected to improve, but it will be tempered by post-pandemic economic realities and the depletion of one-time funding sources. At the same time, the cost of city services is projected to grow significantly, widening the gap between expenditures and revenues and resulting in much larger deficits if the imbalance isn’t corrected.

Source: SPUR analysis of the City and County of San Francisco’s five-year financial plans.

The current budget process prioritizes short-term fixes over long-term structural change. While discussions about the structural deficit occur early in every budget cycle, they are overshadowed as the mayor, Board of Supervisors, department directors, and the public shift their focus to immediate fixes that will help them achieve a balanced budget. Often, those most affected by potential budget cuts dominate conversations, sidelining meaningful discussions about the structural nature of the deficit. As a result, critical decisions are postponed, exacerbating financial challenges.

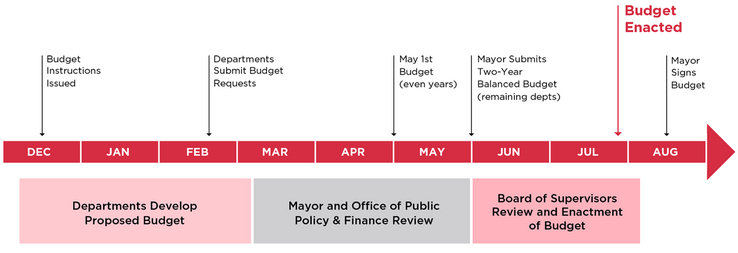

What’s the Process to Pass a Balanced Budget?

Every two years, San Francisco’s mayor and Board of Supervisors work together to adopt a balanced budget that establishes the city’s service and program priorities for the next two fiscal years and allocates resources to pay for them. The fiscal year for the city and county begins on the first day of July and ends the last day of June the next year. By law, the budget must be balanced every year for the next two-year cycle, meaning that there must be enough revenue coming in to meet planned expenditures in that time period. A handful of departments have “fixed” two-year budgets, meaning that every other year they propose and approve a two-year budget, and in the off year they make only small and necessary changes. These departments include the Municipal Transportation Agency, the Public Utilities Commission, the San Francisco International Airport, and the Port of San Francisco. The rest of the city’s departments operate on a “rolling” two-year cycle. This means that a full budget process is undertaken every year, with the fiscal year that was the second year in the last cycle being the first year in the next cycle.

The City Charter and Administrative Code establish the process and timeline that the city follows to arrive at a balanced budget. They lay out the roles and responsibilities that the mayor, the Board of Supervisors, department directors, and the public play in the process.

The budget process is outlined in the Administrative Code and runs from November through August every other year

Source: SPUR’s adaptation of the City and County of San Francisco’s "Budget 101," slide 8.

November–December: Budget Plans and Instructions

The controller, the mayor, and the Board of Supervisors begin the annual budget process in the fall, by creating the Five-Year Financial Plan. The plan forecasts expenditures and revenues during the upcoming five-year period, proposes actions to balance revenues and expenditures during each year, and discusses city departments’ strategic goals and resources. This plan, mandated by Prop A, which voters passed in 2009, informs the upcoming budget process.

Using projections in the Five-Year Financial Plan, the mayor issues budget instructions to city departments, along with broad guidance about how to prepare their budgets. For years with a projected general fund deficit, the mayor instructs departments to reduce their use of general fund revenues by a certain percentage each year. Along with budget instructions, the mayor provides policy instructions. Based on mayoral priorities, some departments, programs, and services such as public safety and homelessness assistance may be told that they are exempt from making reductions.

December–February: Department Proposals

City departments hold public hearings, either through the commission that oversees their department or through a publicly noticed meeting, to present their budget proposals and gather input. Departments submit their proposed budgets to the city controller, the mayor, and the Board of Supervisors by February 21.

March–June: Mayor’s Proposed Budget

The Mayor’s Office analyzes each departmental budget proposal to understand its policy and service implications and impact on the mayor’s priorities. During this time, the mayor will convene departments to address discrepancies and resolve duplication in services or to find additional cost savings.

The mayor is required to submit a proposed two-year balanced budget to the Board of Supervisors for some departments, as determined by the city controller, on May 1 and to submit a full budget, including all city departments, by June 1.

June: Board of Supervisors Approval

On submission of the budget to the Board of Supervisors, the board’s legislative analyst takes two weeks to review the budget and prepare recommended adjustments for the board to consider. This analysis predominantly focuses on changes to the city’s budget from the previous year. Generally, anything approved in a previous year’s budget and remaining unchanged is unlikely to be reviewed as a part of this process.

Starting in the second week of June, the Budget and Appropriations Committee considers changes to the mayor's proposed budget, including budget recommendations of the board’s legislative analyst. The public can attend hearings to give feedback during this stage. By the end of June, the committee works to revise the mayor’s budget through a series of budget reductions and subsequent “add-backs” to programs and services that are important to their districts.

July: Final Budget

By the end of July, the Board of Supervisors approves the budget and sends it to the mayor for final approval.

How Did San Francisco’s Structural Budget Deficit Arise and What Can Be Done About It?

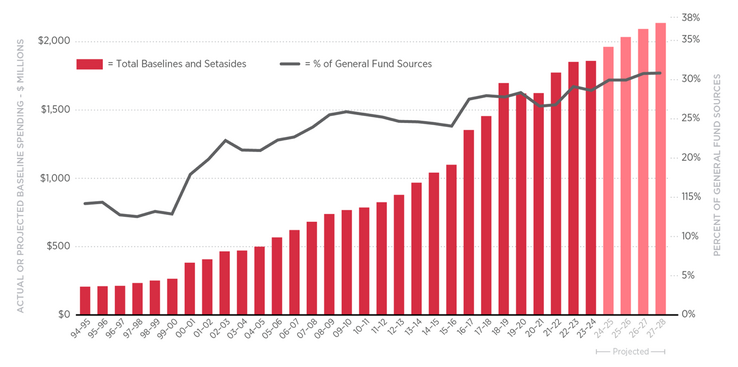

San Francisco’s budget challenges didn’t happen overnight. In the 1970s, California voters approved Proposition 13, which capped property taxes at 1% and immediately caused local government revenues to plummet by 60%. Budget shortfalls have been a recurring problem for local governments across the state ever since. Prop. 13 forced them to find alternative revenue streams to make up for the losses as well as to account for the rising costs of labor and materials. In San Francisco, the result has been a number of voter-approved tax measures that are more restrictive than property taxes. As voters continue to add spending mandates to the City Charter, city policymakers have less and less discretion over the General Fund, which limits the city's options for addressing the structural deficit.

Voter-approved baselines and set-asides have consumed a growing share of the city’s financial resources

By 2028, more than 30% of the General Fund will be dedicated to various programs, up from 14% in 1995.

Source: San Francisco Controller’s Office, March 2024 Joint Report.

The budget process also imposes constraints on the city’s budget. Short review processes, staffing limitations in the Mayor’s Office, and public engagement that happens late in the process all contribute to short-term rather than long-term decision-making.

Given these constraints, city leaders face a daunting challenge in closing the fiscal deficit. With rising costs, significant long-term liabilities, the depletion of one-time revenue sources, threats to state and federal grant funds, and long-term COVID-19 impacts to the city’s key revenue streams, there will be no easy or short-term fixes for balancing the budget. Setting San Francisco on the right track will require the political will to make hard decisions and a collective effort to make short-term sacrifices for long-term financial stability. Many of San Francisco’s programs and services will be affected.