This summer, after a two-year hiatus, SPUR resumed its annual study trip to learn from other cities around the world. See the bottom of this page for links to all of our articles on this year’s trip to Copenhagen.

Copenhagen has set a goal to become the world’s first carbon-neutral city by 2025. On our study trip this summer, we learned that the city’s commitment to sustainability is embedded in its long-range land use plans and goes back to the middle of the 20th century. Copenhagen’s success in realizing these plans comes from a strategic combination of investments and partnerships that have made it possible to create urban neighborhoods with mixed-income housing, transit access, bicycle lanes and green infrastructure. Together, all of these efforts contribute to the goal of a zero-carbon city.

The city’s decisions about land use planning and development today are influenced by two foundational planning documents: the 75-year-old Finger Plan and the 10-year-old Copenhagen Climate Plan. Though conceived at very different times in the city’s history, these plans complement one another and both point toward creating a more sustainable and livable city. Together they have led to the creation of new sustainable districts that connect to transit and bicycle networks and function as “five-minute neighborhoods,” in which residents, workers and visitors can access work, shopping, schools and other everyday amenities in five minutes or less without having to rely on a car.

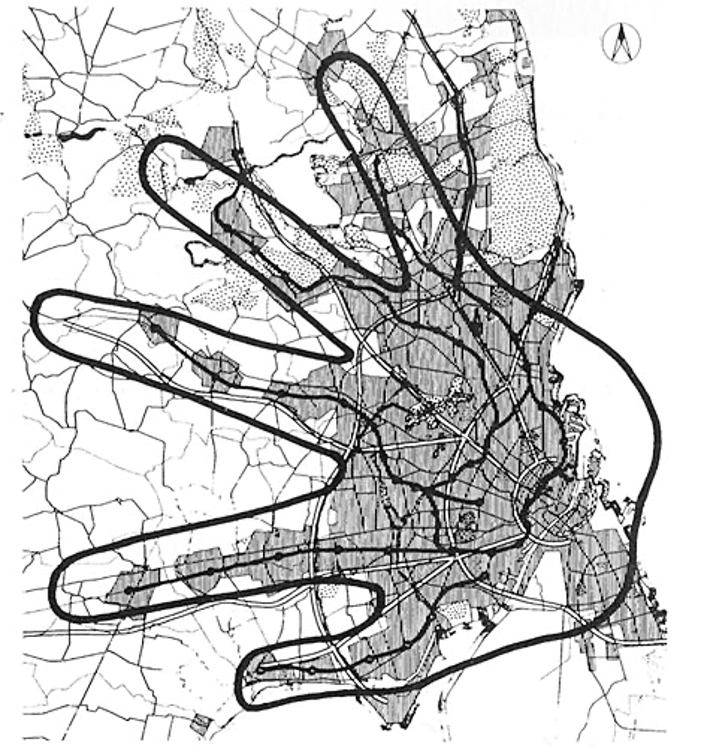

Copenhagen’s Finger Plan was originally developed in 1947, as Denmark was recovering from World War II and German occupation. It organized new mixed-use development within the core urban area of the city (the palm of the hand) and along five major transit corridors (the fingers), separated by green spaces where development was not allowed. The Finger Plan has evolved over the years. Some of the fingers have shortened and others have lengthened, and the city has built a new transit line — the Metro City Circle Line or M3 — to better connect the fingertips. But the general growth framework of the Finger Plan still governs regional growth.

The Copenhagen Climate Plan, adopted in 2012, establishes the goal to become the first carbon-neutral city in the world by 2025. The Climate Plan reinforces sustainable growth patterns by reducing dependence on cars, increasing investments in transit and bicycle infrastructure, emphasizing the importance of recycling and reusing buildings and materials, and establishing green energy and infrastructure systems.

As mentioned in our articles on how Copenhagen has approached redevelopment and housing, the city experienced significant economic decline in the decades after World War II and, in 1990, kickstarted a coordinated revitalization effort focused on improving existing housing stock, investing in infrastructure and attracting development on underutilized public lands. Using value capture tools, the city and national government used the improved properties to generate revenue and establish a perpetual funding stream that keeps investment and improvements continuing over time. These efforts to transform Copenhagen succeeded in attracting a significant amount of growth and development. From 2004 to 2020, the population of Copenhagen increased grew from 600,000 to 730,000, an increase of 130,000 residents. In 2021, Monocle magazine ranked Copenhagen the most livable city in the world because of the quality of life it offers residents.

One of the city’s most successful sustainability investments was in cleaning up its waterfront. Like San Francisco, Copenhagen is a picturesque city almost surrounded by water. But until fairly recently, its harbor and canals were polluted and unsafe for swimming. That’s because until the 1990s, all of Copenhagen’s wastewater was discharged directly into the city’s harbor. To clean up the polluted harbor, the city made a $440 million investment to redesign its wastewater system so that the overflow drains into reservoir systems instead of the harbor. An alarm system warns city employees of a pending overflow event due to storm surges or tides. Today, the harbor has been transformed into a recreational asset for all Copenhageners. In 2002, the city opened the first of four swimming areas including platforms, swim lanes, showers and even saunas at Islands Brygge. Nowadays, even in the coldest winter weather, city residents can be found swimming or boating in the harbor and canals.

The cleanup of the harbor has contributed significantly to the desirability of the waterfront for new development, especially in the North Harbor and South Harbor areas. North Harbor development has been designed so that every part of the district is located within a short walk of the water, including safe swimming areas and canals.

Lessons for the Bay Area

The Bay Area is also a leader in sustainable planning, but some of our landmark environmental laws are now out of date, and others have yet to be effectively implemented. How has Copenhagen been able to make progress, and what can the Bay Area learn from its success? Here are four basic principles we can look to:

Lesson. 1 Make large-scale infrastructure investments to facilitate major redevelopment.

The Bay Area, like the greater Copenhagen region, has a long-range planning document in the form of Plan Bay Area, which prioritizes growth near transit and in infill areas. However, unlike Copenhagen, the Bay Area has not always successfully followed through in making the infrastructure investments necessary to facilitate the planned development. In Copenhagen, the city and national governments have made strategic infrastructure investments (water systems, metro stations, bike networks) and taken a much more proactive approach to redevelopment in former industrial areas and military bases.

Though we may not have the same large waterfront opportunities in the Bay Area, there are many underutilized commercial corridors that could be up-zoned to accommodate new housing and mixed-use development, and potentially even generate revenues to help pay for the necessary infrastructure.

Lesson 2. Develop strong mechanisms that encourage local jurisdictions to follow through on regional plans.

Planning works best at a scale that goes beyond the hyper-local. In the greater Copenhagen area, the national government has supplemented local infrastructure dollars to create a regional bicycle superhighway, rather than creating a piecemeal approach that relies on every city to fund a segment on its own. The Bay Area has regional planning documents, but we lack the mechanisms to ensure its successful implementation at the local level. While the state has implemented some accountability measures and “sticks” to ensure that cities follow through on planning for housing, there are other “carrots” we could be pursuing to encourage jurisdictions to comply with planning documents and bring forth more development. For example, the state or region could reward cities that have successfully accommodated new housing development with infrastructure dollars for wider sidewalks, bike lanes, and other important infrastructure.

Lesson 3. Invest in quality of life to create value, which in turn will support future investments.

Copenhagen’s investments in its waterfront and its public realm, streets and parks have all added to the city’s quality of life.

The waterfront cleanup made the harbor locations more popular and added value to adjacent land. Public realm investments have made the city as a whole attractive to residents, businesses and visitors. Investments in bicycle lanes, the metro system and other mobility improvements have made it easier for commuters and families to get around without a car. All of these investments amplify the quality of life and desirability of the urban core, which translates into higher land values, which in turn generates the tax revenues that allow the city to keep making further investments in quality of life. Oakland, San José and San Francisco could all take a page from Copenhagen to make more strategic investments and prioritize quality of life. If we make our urban areas places where people actually want to be, we too can create a virtuous funding cycle with tangible benefits for more people.

Lesson 4. Use greenhouse gas emissions as a primary metric for decision-making about development and infrastructure projects.

In Copenhagen, the city and national government make decisions about major infrastructure and development projects after evaluating the carbon footprint of each alternative, with the goal of reaching carbon neutrality by 2025. The Copenhagen Climate Plan is central to decision-making about projects like new roadways, transit, redevelopment districts and building standards. The redeveloped North Harbor district is expected to achieve carbon neutrality, and has received the prestigious gold certification from DGNB for its green building and sustainability standards.

In contrast, California and the Bay Area still evaluate the environmental impacts of projects using outdated environmental metrics and laws like the 1970 California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which does not even include an evaluation of a project’s carbon impact. In fact, the lengthy CEQA review process is often misused to stall or block environmentally friendly housing and transportation projects. It frequently results in bureaucratic delays and cutbacks for important transportation projects like the dramatically truncated East Bay Rapid Transit project, which would have significantly improved mobility and reduced reliance on cars.

Rather than clinging to outdated standards, the state and the Bay Area region should explore alternative ways of evaluating the environmental impacts of projects that advance our climate goals. Enacting state bills like SB 288 and SB 922 to exempt certain sustainable transportation projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions is a step in the right direction. The Bay Area and California should expand the exemption to allow more projects to be fast-tracked, including sustainable housing development and green infrastructure projects that would reduce the region’s carbon footprint and help it achieve carbon neutrality on a faster timeline.

Conclusion

The Bay Area prides itself on being a pioneer in sustainability. For example, it was the first region in the U.S. to create a regional transit-oriented development policy that required cities to plan for housing near new transit lines in order to receive regional funding. Plan Bay Area envisions that by 2050, 70% of low-income households will live within one half-mile of high-quality transit. SPUR’s visit to Copenhagen showed us that in order to reach its goals, the region must follow through on its planning by making significant investments in infrastructure and quality of life for residents, update environmental laws, and create stronger mechanisms to ensure that cities are complying with the vision for growth. To meet our ambitious goals, the Bay Area and California must enact the right policies and make the strategic investments necessary to transition communities to be healthier and more sustainable.

Read more about the study trip:

How Copenhagen Can Inspire Bay Area Cities to Go Big on Bikes

Finding a Way to Build: Can the Bay Area Learn from Copenhagen’s 1990s Reinvention?