This article is a product of a partnership between SPUR, the Danish Energy Agency (DEA), and San Francisco Department of the Environment (SF Environment). The DEA has an agreement with the California Energy Commission to exchange information on energy efficiency. In 2021, the SPUR, DEA and SF Environment partnered on an

Governor Newsom recently announced a goal of making 14 million California homes climate-friendly by 2035 by switching all of their energy use from fossil fuels to electricity. This would account for nearly 50% of California homes, a first step toward the goal of fully decarbonizing all buildings

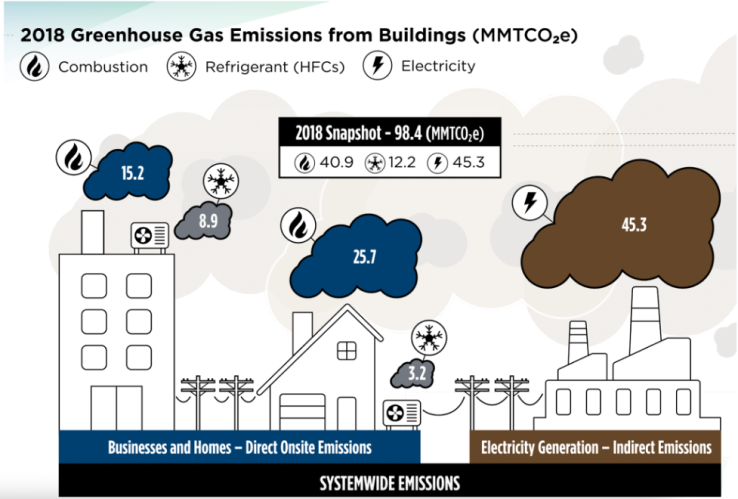

Buildings release 25% of greenhouse gas emissions in California, through use and leakage of natural gas, leaks of refrigerant chemicals found in refrigerators and air conditioners, and use of electricity that was generated from fossil fuels.

Homes and businesses produce 94.4 MMTCO2e, a quarter of the state’s total greenhouse gas emissions. MMTCO2e stands for million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents. It’s a standardized measurement of the global warming potential of various gasses.

Image courtesy of California Energy Commission.

Despite the

But sometimes, decarbonizing a building isn’t all that hard, the owners are equipped to shoulder the costs, and obtaining permits is fast and straightforward. Those cases are worth examining, because the state needs early movers to build a robust market for zero-emission technology to bring costs down for others.

Enter the SPUR Urban Center. Built in 2009 to LEED Silver standards, SPUR’s downtown San Francisco headquarters was designed to be a community gathering space and a symbol of the region’s sustainability values. The building is already

Disconnecting the Urban Center from natural gas is as simple as swapping out the building’s four heating, ventilation and cooling (HVAC) units for electric heat pumps, highly efficient devices that can both heat and cool the building.

While converting to heat pumps is an extra expense over replacing our old gas heaters like-for-like, it’s a cost SPUR can absorb in our budget as long as we plan for it. The energy audit also identified

One complication in electrifying a building is that increasing the peak electrical load can trigger the need for electrical service upgrades. Electrical service is the equipment that determines the maximum capacity to deliver electricity to a building; it includes the breaker panel and wiring to connect the building to the electrical grid. The cost and timeline for electrical service upgrades are hard to predict, and for certain unlucky residential projects they can reach costs as high as $30,000 and take upwards of nine months to complete.

There is one snag in all this good news: SPUR, with its well-insulated building located in temperate San Francisco, uses so little energy to heat its building that it’s hard to make an economic case for decarbonizing. No matter how much you save on a $60 monthly gas bill, it’s still pocket change. SPUR is motivated to decarbonize because of our values. But building owners focused on the bottom line wouldn’t take on electrification just for the utility bill savings.

That’s why San Francisco has set a goal of requiring all large commercial buildings to decarbonize by 2035 and smaller commercial buildings to follow suit by 2040. Regardless of the economics, all commercial buildings should be laying their plans to decarbonize now, because by far the least expensive time to switch to a heat pump is when the old appliance reaches the end of its useful life. Since hot water heaters, furnaces and boilers have mean lifetimes in the range of 15 to 25 years, any gas appliances installed between now and 2040 have a high probability of needing to be replaced before they fail — a waste of money and materials.

What we learned:

- Having a plan in place allows the building owner to take advantage of the opportunities presented when old appliances fail and need to be replaced.

- The technology to decarbonize buildings is available now, and for the Urban Center, the incremental cost is modest.

- Identifying energy-saving measures in tandem with planning for decarbonization has several benefits. Efficiency yields bill savings that help offset the cost of converting to heat pumps. In our case, optimizing the air circulation in the building may enable us to buy smaller, less expensive heat pumps.

- Reducing our building’s demands on the grid — especially during peak energy use hours — doesn’t benefit us alone. As California shifts nearly all of its energy use to electricity, daily peak demand is likely to rise, straining the existing grid. It is the responsibility of each electricity user to find ways to moderate their demand during peak hours.

- The undertaking won’t cost much. The incremental costs are between $2,000 and $4,000 total to install heat pumps instead of gas-powered heat. Costs like these are well within reach for most institutions and businesses, and even nonprofits like SPUR.

- This case study shows there are buildings that are easy to decarbonize and where the owner has the resources to shoulder the upfront costs. Targeting these properties with incentives and regulations to decarbonize early can grow the supply chain — from manufacturing to vendors to contractors –—which helps bring down costs for everyone.

Read the complete energy audit.