This summer, after a two-year hiatus, SPUR resumed its annual study trip to learn from other cities around the world. See the bottom of this page for links to all of our articles on this year’s trip to Copenhagen.

Each year SPUR organizes a study trip to learn from another metro area about how it addresses urban challenges and adapts to change. We were able to resume this trip in 2022 and had the pleasure of meeting with architects, urban planners, developers and project managers in the Danish city of Copenhagen. Making this trip during the ongoing but evolving pandemic offered a new perspective into how the city has forged ahead on major projects and responded to changing circumstances.

Over the last 100 years, Denmark has taken structural and local policy implementation approaches to housing that have much to teach the Bay Area. We got to meet leaders in government, architecture, housing and sustainability who shared their insights and fielded our group’s many questions about how the city renewed its urban core without demolition and how it builds two types of housing that we don’t have: social housing and housing co-ops. Here’s what we learned.

Redevelopment Without Demolition

Copenhagen has become a city synonymous with urbanist ideals, renowned for walkable, people-scaled neighborhoods, well-connected transit systems and pioneering environmental urban design. But this has not always been the case. Copenhagen was on the brink of bankruptcy in the early 1980s. The city had been facing a constant and growing budget deficit that reduced its ability to cover public benefits and, as a result, had seen a dramatic drop in population. Over a third of Copenhagen residents had fled the city center for the suburbs, largely due to better housing conditions and the availability of undeveloped land. Apartments within the urban core were older, decaying and most rentals too small for growing families; the average apartment was a two-room unit with shared bathroom facilities. As a result, many of the remaining city residents were unemployed people, students and pensioners who could not contribute greatly to the city’s tax revenue, which led to a lack of resources for public amenities and improvements.

Beginning in the late 1980s, political leaders gathered wide support for a plan to transform Denmark’s capital city by investing in housing and infrastructure to strengthen the tax base. A key undertaking was the modernization of existing housing in the central core, a process that took as a central aim the inclusion of local residents in planning. The city provided sizable grants to physically upgrade decaying buildings instead of demolishing them.

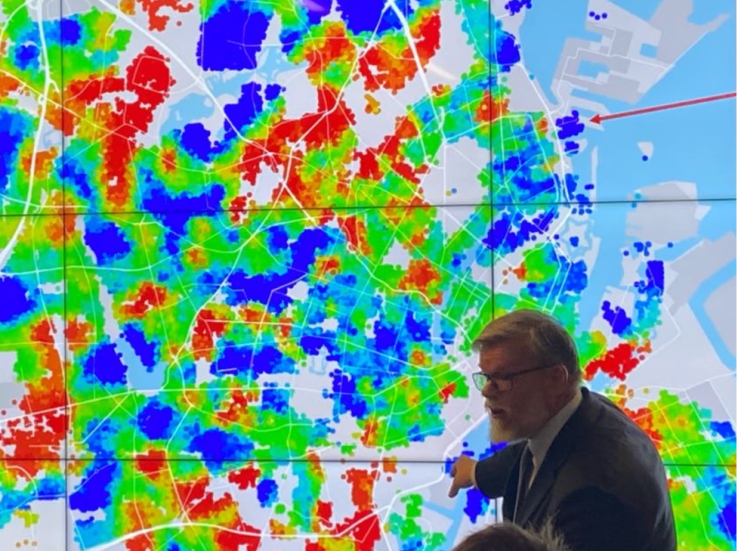

The plan worked and the city’s revenue base stabilized. But over time, these policies — combined with market dynamics and a lack of anti-displacement measures — contributed to a loss of housing affordable to lower income households. In response, Copenhagen policymakers and researchers have increasingly used data to better understand the impacts of policies in order to adjust for outcomes on both a micro and macro scale. We talked to Curt Liliegreen from the Housing Economics Knowledge Center at Realdania, who shared research and outcomes that have demonstrated Copenhagen’s ability to respond to broader housing issues with practical and data-informed solutions. For example, when population data distributed by the socioeconomic neighborhood index showed increasing displacement and segregation patterns by income, local government leaders pursued policy changes to reinstate smaller units as a naturally affordable housing solution by reducing the minimum residential unit size from 90 square meters to 50 square meters. This allowed the housing development sector to more nimbly provide for a missing housing solution in a quickly growing city.

Social Housing

Denmark’s history of equitable housing policy goes back over 100 years. In 1919, by broad political consensus, Denmark established a national public social housing system that is open to all. Unlike public housing in the United States, social housing is not restricted to low-income households in Denmark; it is available to anyone. Nonprofit housing organizations develop and own the buildings, and residents influence their living conditions through a system of tenant democracy. Nonprofit housing development is an integral part of Danish welfare policy and is therefore highly regulated in terms of financing, design, construction and management (which includes waiting lists for housing units). By Danish law, each municipality is eligible to reserve up to 25% of its social housing stock for communities such as refugees, unemployed people and people with disabilities. Social housing accounts for about 20% of the housing stock in Copenhagen. Market-rate rentals and homes make up 43%, and private co-ops, which we’ll dive into later, represent another significant portion.

Capital for building social housing comes from a national funding institution known as the Landsbyggefonden (National Building Fund or Revolving Renovation Fund). This independent institution is governed by a board of directors with oversight of nonprofit housing development organizations. The fund’s level and areas of investments are agreed upon every four years by the Danish Parliament. As social housing projects repay their loans, the Landsbyggefonden receives more capital, which allows for a sustainable funding cycle for construction costs and a consistent funding mechanism for ongoing large-scale maintenance and renovations of social housing properties.

In the United States, public housing is restricted by income level. Affordable housing developers who build housing often have to cobble together financing from bank loans, tax credits such as the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, federal block grants, rental assistance and many more sources. It is not uncommon for affordable housing developers to rely on 20 or more financing sources to fill the gap of total costs to begin construction. In Denmark, because the nonprofit housing development sector is more simplified and receives its financing largely from the Landsbyggefonden, the financing breakdown for social housing construction is fairly straightforward:

- 10% of construction funding comes from a soft no-interest loan from the city for a 50-year term

- 88% of construction funding comes from a government-backed real estate loan (from the Landsbyggefonden) with a very low fixed interest rate for a 30-year term

- 2% of construction funding comes from tenant rents

The Landsbyggefonden is authorized by the Danish Parliament to spend its funds (estimated at $505 million in 2019) only for the following types of activities:

- Co-financing projects within the social housing sector, such as renovation of buildings, improvement of infrastructure and social efforts in challenged housing areas

- Providing subsidies to regulate tenant rents

- Financing research and analyses of the social housing sector

- Social work including tenant services and master plans to strengthen disadvantaged communities

Because the financing is almost entirely from government-backed, low-interest-rate loans, the rents for social housing can be set based on actual operating costs and do not fluctuate based on market conditions. Tenants exert some control over the operating budget, repairs and overall maintenance, which are overseen by nonprofit housing organizations. Because construction and land costs have increased steeply in Copenhagen over the past decade, new social housing units tend to be more expensive to rent than older ones, and rents must cover the full operating costs, including financing.

During the study trip, we spoke with KAB, a nonprofit housing organization that manages over 70,000 housing units in greater Copenhagen. As part of the social housing model, the organization provides management and facility services, as well as support for organizing democratic tenant decision-making. Neither the nonprofit organizations nor the self-funded Landsbyggefonden are required to meet economic returns for investors, which has given KAB the freedom to explore innovations in housing construction and maintenance. KAB shared a number of their new approaches to building sustainably, including new building practices to increasingly use treated wood and recycled building materials.

Housing Co-ops

In Copenhagen, just over 30% of the housing stock is made up of private co-operatives (co-ops) or andelsbolig. This housing structure has a long legacy in Denmark, where law stipulates that property owners interested in selling a block of six apartments or more are first required to provide existing tenants with the option to buy. Tenants purchase a share in the co-op entitling them to live in one of the apartments.

Because co-op tenants collectively own their units, expenses for ongoing maintenance and substantial improvements are also collectively shared, meaning that decisions must be made and agreed upon by the tenant board. This body can then deliberate and make decisions about approving the cost, for example, to finance a new roof.

When a tenant decides to leave the andelsbolig, they have the option to sell to someone on the co-op’s waiting list or to a friend. Because of regulations placed on co-ops, prospective tenant sellers cannot set their own asking price. The pricing is instead formulated as a percentage value of the entire co-op development, and takes into account the building’s outstanding debt (which may include upgrades to units or structural improvements).

On the study trip, Copenhagen city councilmember Marcus Vesterager shared with us that co-ops have provided an entry point to stable housing for many that isn’t dictated by market value — but this housing system is by no means perfect. The demand for co-ops is higher than the available supply, which often means that many andelisbolig have years-long waiting lists. Anecdotally, Vesterager shared that oftentimes when a co-op tenant chooses to leave, they offer their unit to a friend, or a friend of a friend (sometimes with an added fee), which removes many of these comparatively affordable units off of the open market. He took us on a tour of his council district, Nørrebro, where we visited Jægersborggade, a well-known street with a concentration of higher-income co-op developments. Many of the co-ops on this street had made major structural improvements to their units and ground floors, including renovating the interiors and façades of their buildings, which ultimately increased the value of their asset and neighborhood. He sees this area as representative of the gentrification that wealthy co-ops can spark in neighborhoods that were formerly known for their multicultural population and sometimes cast as dangerous.

Lessons for the Bay Area

Many of Denmark’s housing options are products of broad political consensus between Danish citizens and leaders — a very different foundation from our political and economic system in the United States. There are many differences between what Copenhagen has been able to achieve and what is possible in the Bay Area, largely due to the ability of Danish leaders to be nimbler and more effective in responding to unintended policy outcomes. But Denmark’s successes can still provide guiding paths to affordable housing policy in the Bay Area. The challenges the Danish have overcome in implementing their policies offer valuable lessons for achieving equity and sustainability in housing practices.

Lesson 1. Vastly simplify financing for affordable housing.

In the United States, developers must rely on a patchwork system to identify and pursue financing for projects. This system already includes substantial public money for affordable housing. Denmark’s system of nonprofit housing development uses simplified mechanisms to secure financing, and has established a system of loan repayment under a revolving fund. A key takeaway for the Bay Area is to move toward a system of housing where certain types of housing are not expected to generate a return so much as sustain a revolving fund. One important step toward this goal is to place land and buildings in public or nonprofit ownership to encourage long-term housing affordability. By empowering a new regional housing finance agency to acquire, manage and dispose of land and property, the region can enact effective policies that maintain affordable housing under a simplified and revolving fund that can be supplemented by public and philanthropic institutions.

Lesson 2. Diversify tenant and owner incomes within buildings.

Existing social housing and co-op models in Denmark offer lessons on income diversity within buildings. Affordable housing policy in the Bay Area often skews toward encouraging 100% affordable projects, where all of the units are subsidized for low-income households. But this approach fails to account for the difficulties in scaling up housing development. The Bay Area needs to produce a significant number of units in order to address its housing shortage — and it cannot meet this goal when developers are challenged to build projects that must be almost entirely covered by government subsidies. Having a diversity of incomes within buildings allows for more flexible ways of meeting repayment terms, and it has wider social benefits. Research continues to find that upward mobility tends to reflect socio-economic proximity. Raj Chetty’s findings, including the Opportunity Atlas, show the importance of what he calls “cross-class interaction,” or interaction in childhood with people from different socio-economic groups.

Lesson 3. Continue pursuing co-operative housing policies, and set price controls to protect affordability.

Laws establishing tenants’ right to purchase their units have led to a substantial and comparatively affordable housing option in Denmark, where purchasing a stake in a co-op essentially represents a step in between renting and home ownership. Regulations on selling prices and tenant co-op management provide guardrails against market forces in cities like Copenhagen. These models, and their challenges in implementation, inform next steps for Bay Area cities, where jurisdictions such as San Francisco and San José have begun to make headway in furthering co-operative housing policies, such as the Community Opportunity to Purchase Act (COPA) and Tenancy In Common (TIC). However, the Bay Area can also enact price controls on subsidized nonprofit co-ops that can be structured and regulated between ownership transitions. This would solve for the patterns of exclusion in the current Danish co-op housing model, where tenants often sell their unit to a friend or other well-connected buyer.

Lesson. 4 Consider other income policies that complement affordable housing.

Denmark’s national housing policies have led to a social housing system that is not income restricted, and the country has the benefit of over a century of implementing equitable housing construction and management. But the system’s success is also in part due to a nation-wide network of safety nets that provide for broader social benefits. Denmark’s welfare state policies provide free universal access to healthcare, sick leave, education, transportation and unemployment benefits. In fact, university students are paid to attend school. Additionally, Denmark’s labor market model operates under a system where pay and working conditions are established by collective-bargaining agreements between trade unions and employer organizations. As a result, (except for a few emerging labor markets) much of the country’s workers earn livable wages. Denmark’s income policies contribute to a housing system where fewer people need additional income supports and subsidies because they already have access to a wide spectrum of social benefits. Income policies matter when developing and enacting housing policy.

Conclusion

Copenhagen’s and Denmark’s approaches to housing policy, while not perfect, have benefited from political leaders’ ability to course-correct and inform decision-making by looking at data. More importantly, broad political consensus and compromise have allowed Denmark to sustain housing models that can inspire the Bay Area. In a region faced with an extensive housing affordability crisis, we hope that local leaders and communities will be inspired by what could be possible and take action for transformational change.

Read more about the study trip:

The Sustainable City: Learning from Copenhagen’s Plan for Zero Carbon

How Copenhagen Can Inspire Bay Area Cities to Go Big on Bikes

Finding a Way to Build: Can the Bay Area Learn from Copenhagen’s 1990s Reinvention?