Improving equitable access, creating a more resilient transit network and delivering on environmental priorities requires faster and more reliable transit travel on the Bay Bridge. A recent SPUR Digital Discourse highlighted AB455, a bill to deliver better, faster, fairer bus service across the Bay Bridge. The conversation discussed the current state of Bay Bridge transit and tackled the questions why and how to improve transbay bus service. The panel included Assemblymember Rob Bonta (D-Oakland), the lead author of AB 455, Robert Del Rosario of AC Transit, Andy Fremier of Metropolitan Transportation Commission, Carter Lavin of Transbay Coalition, and SPUR’s Jonathon Kass. This article notes highlights from this discussion and related facts about transit priority in the Bay Bridge corridor.

The Bay Bridge Today

About 260,000 cars, trucks and buses cross the Bay Bridge every day — more than one third of all the traffic on all state-owned bridges in California combined. The bridge is a vital link between the East Bay and job centers in San Francisco and the Peninsula, yet some bridge approaches consistently ranking among the most congested corridors in the region.

The Bay Bridge already supports high transit use, with nearly 25% of morning peak hour travelers choosing to take a public bus — double the transit commute rate for the region as a whole. In the broader Bay Bridge Corridor, which also includes the BART Transbay Tube and ferry service, pre-pandemic transit use was exceptional, with nearly 75% of westbound morning peak hour travelers choosing public transit. These statistics demonstrate the need for ongoing transit growth and the large numbers of travelers who would benefit from interventions to improve transit speed and reliability.

One way to make transit faster and more appealing is through transit priority measures, which reduce delays for transit vehicles on congested roads. During the panel, Jonathon Kass spoke of the history of transit priority on the Bay Bridge. Initially, the lower deck was dedicated to the Key System commuter rail, trucks and buses. After the Key System was abandoned and the state removed the rail tracks from the bridge, planners dedicated a lane for buses and designated additional lanes to get buses through the toll plaza.

While currently there is no transit priority on the bridge itself, in the westbound direction, dedicated lanes help buses and carpools bypass the queue to get onto the bridge. Metering lights just west of the toll plaza aim to reduce congestion on the bridge deck by controlling how quickly vehicles are able get onto the bridge. In theory, when the bridge is getting congested, the metering lights can slow the rate that most vehicles are permitted onto the bridge, while allowing buses and qualifying high-occupancy vehicles (HOVs) continuous access. In practice, this system does not work consistently.

Any discussion of transit priority on the Bay Bridge must acknowledge the new $2.2 billion Transbay Transit Center, located in the heart of San Francisco’s job center, and connected directly to the Bay Bridge with exclusive bus ramps. This facility has capacity to handle up to 300 buses per hour, more than four times the number currently operating. In other words, it can efficiently handle projected growth in buses for decades.

Why Commuters Need Change

Better bus service on the Bay Bridge is essential to deliver the capacity and reliability our region needs for the future. The current system too frequently fails to keep buses, vanpools, and HOVs out of congestion. Common problems include traffic backups in the East Bay blocking buses before they can reach HOV lanes that lead onto the bridge, or traffic backups on the bridge itself often due to a traffic incidents, weather or other unpredictable factors. When buses get stuck in this traffic, the resulting reliability problems discourage transit use and obstruct progress toward equity and environmental goals.

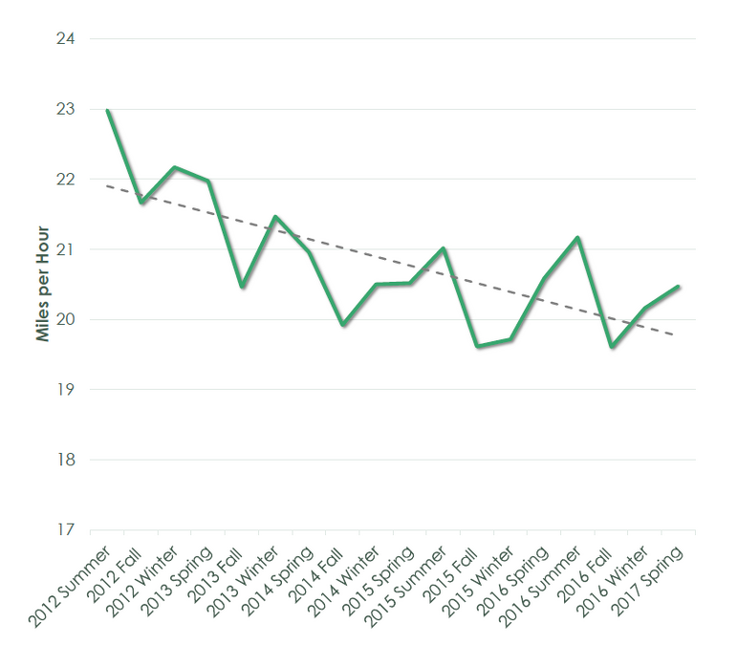

While currently planned projects could improve conditions, they are unlikely to to deliver the capacity and reliability that our region needs. For example, the current draft of Plan Bay Area 2050 assumes 20% of commute trips will occur on transit, a dramatic increase over the 2015 level of 14%. Such transit growth will be hard to achieve without strong growth in the Bay Bridge corridor. During the Digital Discourse, Robert Del Rosario with AC Transit showed that there has been increased demand for transbay buses since 2012. Yet, AC Transit has been seeing decreases in speed over the past eight years.

There are signs that post-pandemic conditions may create even more serious problems for transit reliability. We don’t yet know the scale of long-term changes to commuting patterns, but we see a disturbing trend of significant growth in traffic congestion even before the majority of office workers have returned. For example:

- The Muni Route 25, which travels only on the Western Span of the Bay Bridge between the Transbay Transit Center and Treasure Island, has faced reliability problems that exceed pre-pandemic conditions.

- In addition, AC Transit’s transbay bus lines, though moving more quickly on average, are experiencing even greater variation in travel times, with some of the worst morning commute travel times even slower than pre-pandemic.

As offices begin to re-open, we are likely to confront much slower travel times and further declines in reliability, requiring more tools to prioritize bus and HOV travel going forward.

Carter Lavin, a leading advocate for AB 455, discussed the equity impacts of slow and unreliable transbay bus travel. He highlighted the disparity between those who are able to work remotely and those who are not. While remote work is allowing many to avoid peak travel times, people of color and low-income travelers are disproportionately stuck commuting during congested periods because they are less likely to have the flexibility to work remotely or to have flexibility in when they can arrive to work. Workers with little flexibility must plan every day as if it would be the slowest bus commute day, so the reliability challenges that plague transbay bus service cost some workers many hours of lost time each month.

An additional challenge for planning in the Bay Bridge corridor is the over reliance on BART. In recent years, peak-hour travel has relied on overcapacity BART cars, with pre-pandemic trains frequently at 150% of target capacity. Even after much of the population is vaccinated, it is unlikely that BART will return to operating cars with such intense crowding. At the same time, even a 10% shift of pre-pandemic BART riders to the Bay Bridge (i.e., about 2,500 travelers per hour) would overwhelm buses and traffic. The lack of high-capacity transit alternatives to BART exacerbates this problem. Most transbay commuters are familiar with the severe delays that can result from something as common as a medical emergency on a BART train, or a minor technical failure. More serious problems that could result from a natural disaster or major mechanical failure could bring our region to a halt for months. A more robust transit priority system on the Bay Bridge would support increased bus capacity and serve as a desperately needed backup to the current, precarious transbay transit system.

How Can This Change?

One way to improve bus priority in the corridor is to implement projects that are now being planned and designed. The Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) is currently undertaking multiple efforts under a program known as Bay Bridge Forward. As MTC Deputy Director Andy Fremier explained during the panel discussion, these include the conversion of a westbound I-580 general purpose lane to bus/HOV, westbound I-80 bus access improvements, initial work on I-80 bus HOV improvement from the Bay Bridge to the Carquinez Bridge and a general purpose lane conversion to bus/HOV on the I-580 approach to the Bay Bridge, as well as the extension of the bus/HOV shoulder lane at the West Grand Avenue Bay Bridge on-ramp.

While these projects work towards better transbay transitm Assemblymember Bonta’s bill, AB 455, would authorize more significant action toward Bay Bridge transit priority and produce bigger results. The bill establishes 45 miles per hour as the minimum average speed target for buses between various bridge access points in the East Bay and the Transbay Transit Center in San Francisco. As a reliability target, the bill requires that the speed target must be met 90% of the time.

Meeting these targets will require more than the Bay Bridge Forward program described above. It would also require steps such as:

- Additional transit and HOV priorities on bridge approaches through conversion of existing lanes or targeted use of shoulders

- Improved enforcement of HOV lanes

- Strategies to assure buses and HOVs have priority during traffic incidents and other circumstances causing unusual delay

- Possible dedication of a transit/HOV lane on the bridge itself

Panelist and lead author of AB 455, Assemblymember Bonta explained that the measure does not call for specific projects. Rather, it focuses on the speed and reliability outcomes that really matter to customers. The bill also recognizes that it is not necessary to dedicate a lane for buses alone in order to deliver on transit speed and reliability targets. Transit priority lanes can give access to other vehicles, such as very high occupancy vehicles, as long as such access is limited in a manner that avoids congestion and maintains transit speed and reliability. This means that any transit priority segments can make full use of the roadway, and that other high occupancy vehicles can also benefit.

Of course, planning transit priority projects doesn’t do anything for transit customers without implementation, which can sometimes take many years. Streamlining transit priority projects to allow faster delivery is an important tool to deliver Bay Bridge improvements in the near term. SB288, passed by Senator Wiener last year (co-sponsored by SPUR) helped a number of projects by streamlining transit prioritization projects. Some of the Bay Bridge projects do not currently qualify for this streamlining and could be implemented much more quickly if the law were changed to include these projects.

The Broader Benefits of Transit and HOV Priority Measures

The benefits of fast and reliable bus and HOV speeds across the Bay Bridge will accrue beyond simply the bus and HOV travelers themselves. Transit priority will also reduce operating costs for transit agencies that will be able to spend fewer operating hours to deliver each trip. Even when average speeds are reasonable, transit agencies must build a significant buffer into Bay Bridge travel times to allow for potential delays.

In addition, fast and reliable transbay bus service will be a boon to MTC’s vision of regional express buses, a strategy that SPUR has strongly supported. MTC has identified three pilot routes for enhanced express buses around the region, making use of the region’s growing network of uncongested express lanes. The Bay Bridge is the linchpin for this new regional express bus network. Moving buses quickly through this corridor would drive the success of the broader network.

Transit riders needed to see bold action on transit priority even before the pandemic. Social equity priorities, transit reliability challenges, and the need for more diversified transbay transit options have only increased in urgency over this past year. As a sponsor for AB455, SPUR will be advocating for near-term action to improve bus performance, and longer-term investments that will shift many more travelers to transit and support the level of transbay bus and HOV growth required to meet the region's ambitious equity and sustainability goals.