The Telesis exhibit of 1940, “A Space for Living,” was a seminal event in the history of city planning in the Bay Area. At the time, San Francisco was one of the few major US cities without an independent professional city planning department. Planning ideas were dispersed among smaller agencies and neighborhood institutions, and the public had little understanding of the city planning profession. The Telesis exhibit would help change all this, making the argument for strong, centralized planning, as reflected in the definition of the group’s name: “progress intelligently planned and directed. [1]

The show opened at the San Francisco Museum of Art on June 29, 1940. Over the next several months, the exhibit brought in over 10,000 San Francisco residents to view the promise of comprehensive urban planning .

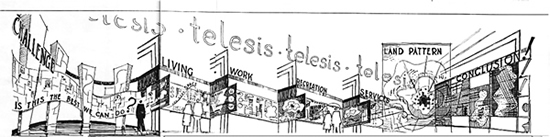

Figure 1: Sketch of Telesis Exhibit by John Dinwidde

Figure 1: Sketch of Telesis Exhibit by John Dinwidde

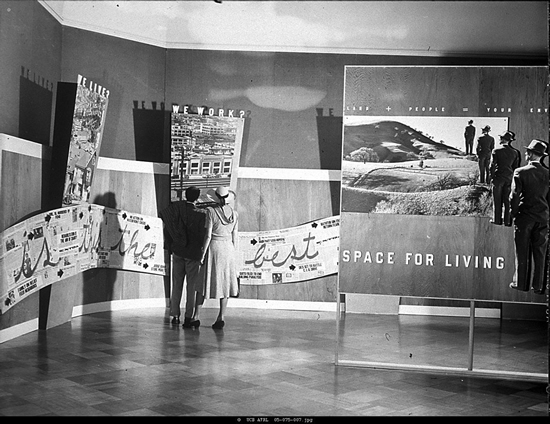

Figure 2: Entry to the "A Space for Living" show. Fran Violich Collection, Visual Resources Center, College of Environmental Design, UC Berkeley

Almost all Bay Area civic leaders and governmental players attended the exhibit. The enthusiasm soon led to the creation of a planning department in 1942, with Telesis members as its first staff members. After the short, ineffective tenure of L. Deming Tilton as the first City Planning Director, Telesis founder T.J. Kent would take over and craft San Francisco’s first general urban plan.

The exhibit also inspired the San Francisco Housing Association to expand from housing reform advocacy to a group concerned with city planning overall, renaming itself the San Francisco Planning and Housing Association, which in turn, became SPUR.

The Telesis Membership

Telesis members were, for the most part, young architects or landscape architects, and perhaps the first generation of native Bay Area designers. Each had adopted a broader concern for social problems during the depression and the New Deal, and turned to planning to solve urban social problems. Perhaps the key image of the group’s beginnings is when Jack Kent and Violich set out in 1939 to gather donations for the Space for Living exhibit, and their first stop was the home of Dorothy Erskine on Telegraph Hill. The meeting brought together two founding members of the group, and the key person that would help their group reach a larger, more significant audience.

The programs of the New Deal, and the contacts made there, played a critical role in the evolution of Telesis. Kent took his first planning job at the Berkeley regional office of the National Resources Planning Board. Violich joined the New Deal’s Farm Security Administration, a program to provide housing to migrant workers and dust bowl refugees. At the FSA, Violich united with Vernon DeMars and Garret Eckbo. Eckbo’s work at the FSA and involvement with Telesis led him to recognize the “importance of social issues in landscape design.” [2]

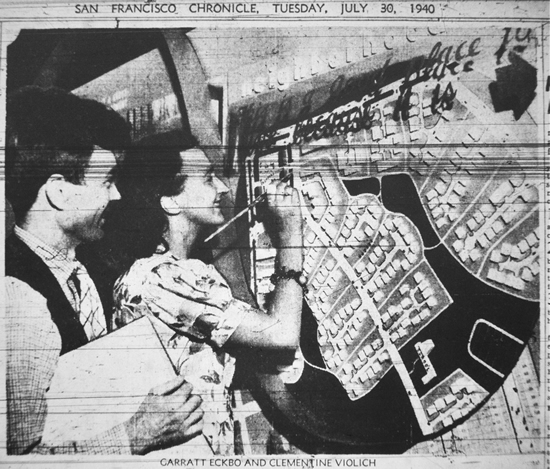

Figure 3: Eckbo and Clementine Violich work on the 1940 Space for Living Exhibit. San Francisco Chronicle, July 30, 1940.

DeMars, who would go on to be one of the Bay Area’s most important postwar architects, also spent time at the Rural Resettlement Agency, where he met Corwin Mocine and brought him into Telesis. Mocine was a landscape architect, but Telesis turned him into a life-long planner.

Meanwhile, at the NRPB, Kent met Mellier (Mel) Scott, a journalist turned planner, and his wife Geraldine, a landscape architect. The connections with Telesis convinced Mel that, “housing was only one aspect of the urban environment and that planning was much more important.” [3] The couple was so impressed by Telesis they started a Los Angeles branch and put on another exhibit, “Now We Plan,” before they returned to the Bay Area for the rest of their careers. [4]

These, then, were the main founders of Telesis. By the summer of 1939 all were in the Bay Area and all shared an interest in finding new solutions to urban problems. They began meeting in various members’ apartments or architecture studios in the North Beach area. Their membership quickly swelled to 40 at the time of the exhibition, and over 100 thereafter. Numerous other design professionals were regular members or contributors, including William Wurster and Catherine Bauer. The most important long-term collaborator, however, was Kent and Violich’s first supporter from 1939: Dorothy Erskine. Along with her husband Morse, Erskine was a leader in the San Francisco Housing Association. Erskine was a grass-roots catalyst, using her network of social and political connections to push for urban planning and renewal, before emerging as one of the Bay Area’s most important environmentalists. Erskine immediately used her important connections to make an impact for Telesis and ensured that many San Francisco political leaders attended the 1940 exhibit, and linked them to future financial and professional supporters.

Telesis and Urban Renewal

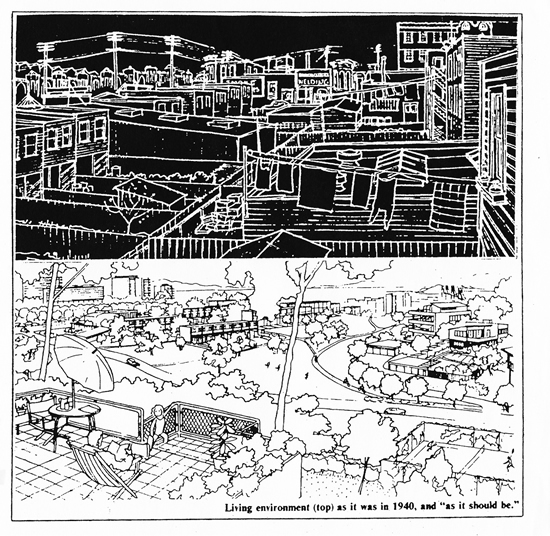

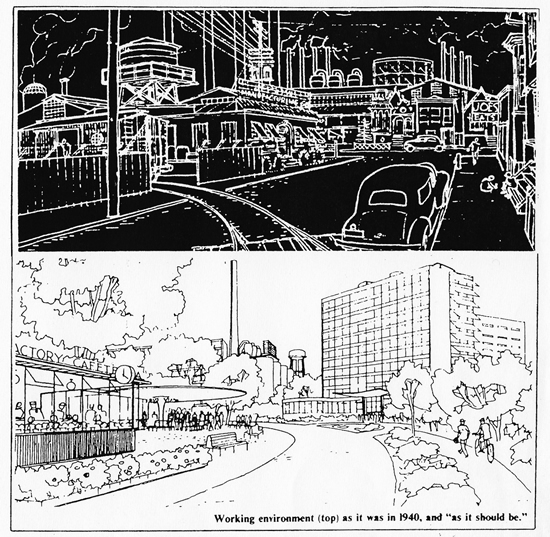

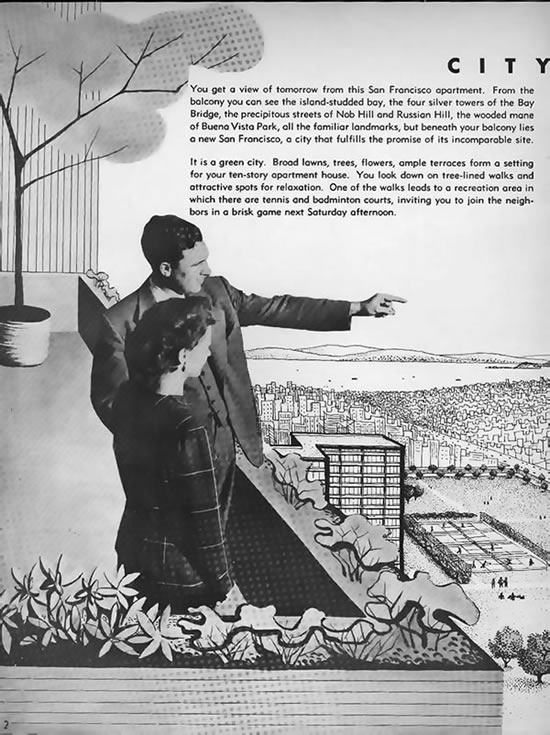

The Space for Living exhibit presented architectural ideas such as the superblock, firmly grounded in the ideas of le Corbusier and the Congress of International Modernism. In their first exhibit, Telesis declared that the “neighborhood unit and super-block treatment will lend economic stability and safer, richer, living.” [5] Sketches by DeMars at the exhibit drew a sharp visual distinction between images of “urban blight,” and the clarity and order of the modernist designs that could replace them.

Figures 4 (top) and 5 (bottom): Sketches by Vernon DeMars for the 1940 exhibition contrast current blight with modern architecture and urban design.) A Space for Living Show. Fran Violich Collection, Visual Resources Center, College of Environmental Design, UC Berkeley.

In 1947, T. J. Kent hired Mel Scott to prepare a report exploring the possibilities of urban redevelopment in the racially mixed neighborhood of the Western Addition. The report advocated that the San Francisco Board of Supervisors designate the Western Addition as a “redevelopment area,” and establish a San Francisco Redevelopment Agency. In the report, Scott wrote of “wide stretches of urban blight are breeding grounds for crime and delinquency, cancerous growths that threaten the vitality of the city.” [6]

Figure 6: Cover of Mel Scott¹s New City: San Francisco Redeveloped, showing the Western Addition Redevelopment zone.

Kent, Violich, and DeMars, along with other Telesis members all went on to play a role in the Western Addition redevelopment, though by the 1950s they had moved on and were largely no longer involved.

Years later, Kent would note in a speech reviewing the history of Telesis that the solutions for public housing that Telesis had advocated did not prove to be good solutions, and they had never solved the slum housing issue. As Kent later described it, the eventual exposure of the “fatal, anti-social flaws in central-city redevelopment programs” revealed their own “professional shortcomings.” [7]

The Greenbelt and Regional Planning

While urban renewal represents the darker realization of the Telesis philosophy, the fight to preserve open space, though also only accomplished only in fragments, remains a brighter achievement. It is important to note, however, that Telesis saw urban renewal and preserving open space as related urban problems. To stop suburban expansion and save the open space, downtown must be saved. The same vision that brought urban renewal to the region’s dense urban populations of minorities, also sought to protect the region’s rural open space, all while ignoring the creation of the region’s spaces of intense pollution concentrated in other minority neighborhoods.

The Telesis 1940 exhibit asked: “The medieval city could have a greenbelt, why not the modern metropolis?” Open spaces, Telesis argued, were being threatened by “a new kind of urban growth.” The exhibit argued for a large part of the city to be dedicated to open green spaces for the health of urban citizens: “Why not bring the agricultural greenbelt to the rescue of our cities.” [8] Moreover the group argued that open spaces and the greenbelt would serve to control urban sprawl, funneling it into denser, compact cities and towns.

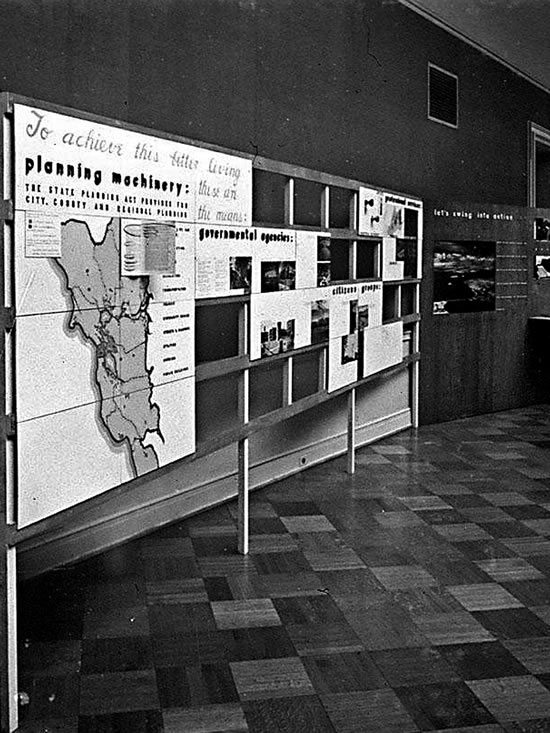

By the mid-twentieth century, a majority of citizens lived within metropolitan regions, but these regions were greatly fragmented among various governments. In the Bay Area of the 1940s, this had resulted in over 100 local governments making separate land use decisions. While the functions of daily urban life increasingly took place across the metropolitan region, government functions were organized as if each city were an isolated and sovereign island. Anticipating the calls of Bay Area environmentalists and progressive planners in the postwar period, Telesis argued that a regional planning agency was the only true solution for planning urban growth, preserving greenbelts, and solving regional transportation issues.

The 1940 exhibition tied the founding of Telesis to the need for regional government, writing that because the lack of strong regional government “exists in our region,” we “young men and women in the related professions of architecture, city and regional planning, landscape architecture and industrial design, have come together and formed this group — Telesis.” [9] Through the regional agency, Telesis aimed to guide “the vast upcoming development toward fresh environmental patterns,” to “organize growth so it would not destroy the integrity of Bay Area cities.” [10]

Figure 7: Regional Planning demonstrated at the 1940 exhibit, "A Space for Living" show. Fran Violich Collection, Visual Resources Center, College of Environmental Design, UC Berkeley.

In 1941, Telesis was already work on a Bay Area Regional Planning Commission Proposal, and a second exhibit of 1941 entitled “Regional Planning for the Next Million People,” was intended to show regular citizens all the regional activities they engaged in during their daily lives, and connect that to the need for regional planning. Corwin Mocine brought the Telesis position for regional planning to the pages of California Arts and Architecture in 1941. Grasping the kernel of a problem that has plagued planners for over half-a-century now, Mocine wrote that while the increased use of the private automobile sapped support for rail transportation, it soon created highways so congested that people would turn back to rapid transit, only to find that due to lack of support, that service was now inadequate. “We,” Mocine wrote, “find ourselves caught in a chain of circumstances that grows steadily more costly.” [11]

The Continued Legacy of Telesis

Telesis would continue to advocate for regional planning in their 1950 exhibit, “The Next Million People,” at San Francisco Museum of Art, which would be their last. World War II and the drastic increase in the Bay Area’s defense industries had dramatically changed the region, bringing tremendous growth. Telesis members were absorbed into the mainstream of the increasing professionalized planning environment, taking jobs in planning departments or teaching in Berkeley’s Department of City and Regional Planning, founded under the leadership of Telesis members.

While Telesis members abandoned urban renewal advocacy, they continued to fight for regional planning and the urban greenbelt. Kent, along with Dorothy Erksine, founded the Citizens for Regional Parks and Open Space, the first open-space advocacy group in the area, which evolved into People for Open Space, and into today’s Greenbelt Alliance. Kent and his group played a large role in steering the regional agency that did emerge, the Association of Bay Area Governments, into a defender of greenbelts. Likewise, under prodding from Erskine, Scott published in 1963 his study, The Future of San Francisco Bay, which described in horrifying terms for the Bay Area public the potential diminishing of the Bay through landfill and shoreline development. The book provided the foundation for civic activism that the Save the Bay trio of Catherine Kerr, Esther Gulick and Sylvia McLaughlin used to pass the legislation creating the Bay Area Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), the agency that has protected the Bay ever since.

The Telesis 1940 exhibit shows that we have been arguing against sprawl and proposing smart growth as a solution for over 60 years. Yet still the debate goes on, centered on the same issues and proposing the same solutions, while continuing to ignore the implicit questions of race and the unequal geography of environmental protection. The Telesis vision of 1940 was one never fully adopted, but its partial realization underscores some of the Bay Area’s most troubled — and most loved — urban spaces.

Endnotes

1 Fran Violich, "Notes from a Telesis Study: Environmental Design and Planning in the San Francisco Bay Region 1939-1953" (November 1976), 4.

2 Garrett Eckbo, "Handwritten Notes," in Garret Eckbo Archives, Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

3 Mel Scott, "Telesis: Promoting Good Design."

4 On the Los Angeles exhibit, see "Dream City," Time Magazine, Nov. 10, 1941; "Now We Plan,"California Arts and Architecture (Nov. 1941), 17-21.

5 "Telesis: The Group and the First Exhibit, 1940," in T.J. Kent Archives, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

6 Mel Scott, "Western Addition District," 3.

7 T.J. Kent, "A History of the Department of City and Regional Planning," in Lowney and D. Landis, Fifty Years of City and Regional Planning at UCBerkeley, 3.

8 "Telesis: The Group and the First Exhibit, 1940," T.J. Kent Archives, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. See also, Corwin Mocine, "Planning for the region", in California Arts and Architecture (April 1941).

9 "Telesis: The Group and the First Exhibit, 1940," T.J. Kent Archives.

10 T.J. Kent, quoted in Violich, "The Planning Pioneers," 34.

11 Corwin Mocine, "Planning for the Region," California Arts and Architecture, (April 1941), 23.