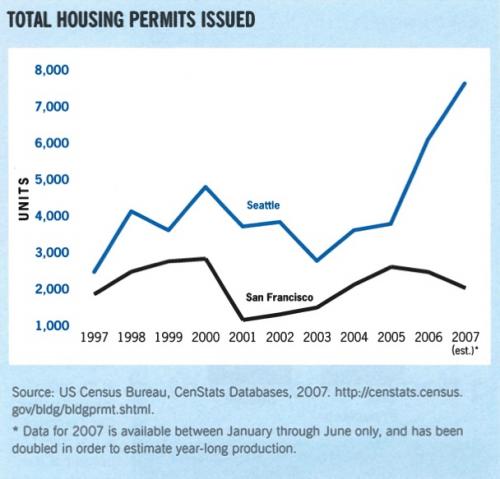

Seattle is famous for its emphasis on neighborhood planning. lts Urban Villages Plan had a huge impact on city planning all across America, including serving as an inspiration for the Better Neighborhoods planning process in San Francisco. But even though growth remains a controversial issue in its neighborhood planning, Seattle has managed to produce around 2,800 new housing units a year for many years, incontrast to a 20-year average of 1,500 a year in San Francisco.

How can we explain this paradox? How does Seattle bring together a culture of infill development with a culture of neighborhood participation in planning? I think the answer has something to do with the role of regionalism in both the civic culture and the planning law that informs development in Seattle.

Seattle has seen a boom in mid-rise construction in its downtown neighborhoods.

A Government That Plans on the Regional Scale

Oregon's growth-management approach has been perhaps the most widely admired attempt at regional planning in the United States. The Oregon system was created by the leadership of a Republican governor, Tom McCall, who led the effort to pass Senate Bill 100 in 1973. This law created the Land Conservation and Development Commission and directed it to address a range of goals defined by the state legislature, including the establishment of urban growth boundaries around cities. In essence, the state required local jurisdictions to do real growth-management planning and local zoning, backed up with statewide authority. Never mind that the “Oregon system" is under attack in Oregon as a result of the property-rights movement. What matters for the purposes of this article is the fact that the State of Washington finally got around to emulating the Oregon law in 1990.

Under Washington's Growth Management Act, the state estimates anticipated population growth, and allocates it to the state's counties. The counties are required to develop and implement comprehensive plans, subject to state approval, that will address that anticipated growth. The plans establish urban growth boundaries along with other land-use designations such as environmentally sensitive areas, agricultural and forest lands, etc. The cities, in turn, must plan for their own assigned population growth to ensure that there will be concurrent development of adequate housing, utility and transportation infrastructure, and public amenities. Counties and cities are also supposed to address economic development.

Based on this statewide framework for growth, the counties (in Seattle's case, King County) tell the cities how much growth will come. And in the case of Seattle — here's where things really look different from San Francisco — the city tells each neighborhood how much growth must be accommodated. Seattle's 1994 Comprehensive Plan, which was called the Urban Village Plan, was the city's response to the 1990 Growth Management Act. It spells out a vision of higher-density urban neighborhoods, concentratingthe growth along transit-served neighborhood commercial streets, with a mix of amenities. in short, it calls for the kind of things we at SPUR tend to promote as good ideas.

Following the adoption of the Urban Village Plan, between 1994 and 1999, 38 Seattle neighborhoods, with support from the city staff and a city-paid consultant, drafted neighborhoodplans to refine and shape that growth. These plans did not result in true changes to zoning, but rather tended toward “wish lists” of public amenities, some of which were able to be fulfilled. But it was a statewide and regional planning vision that served as the driving force for the neighborhood-level planning.

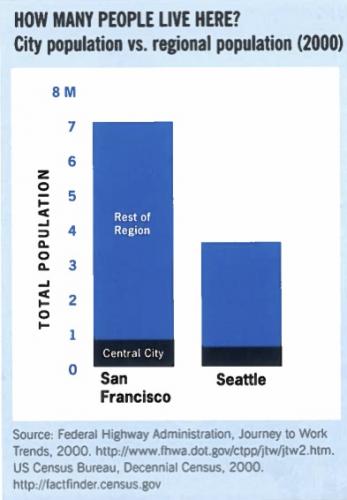

This graph compared the two cities to their respective regions at the time of the last census. San Francisco is just over 11 percent of the region’s population while Seattle is nearly 16 percent.

San Francisco and the Bay Area take essentially the opposite approach to the neighborhood planning. Where San Francisco adds up the growth preferences of the homeowner groups in every neighborhood, and lets this cumulatively determine regional form. Seattle starts with a regional problem that needs solving (where will the region's population growth go?) and derives from that question the scale of change that each neighborhood must accommodate.

The result in Seattle? High-rises in downtown, high-rises in Belltown, and five-story apartments above retail on virtually every single commercial street in the city. For the most part, single-family residential neighborhoods are untouched (with the important exception of official encouragement of secondary “in-Iaw" housing units in a portion town). Some of the new buildings are good, some are bad and some are in between, just like here, but many of the big planning moves are right. Seattle has lots of problems with its urban design a architecture, and it is not a perfect model by stretch of the imagination. Nevertheless, a greater share of Puget Sound's population growth is beingaccommodated in infill locations where people can walk to local shops and where densities are high enough for transit to be possible.

Across all type of housing permits — single family, 2-4 unit, and 5+ unit buildings — Seattle has outstripped San Francisco in issuing permits for housing production for nearly every single year over the past decade. Over that time period (according to these data) Seattle issued over twice as many housing permits (in units) as San Francisco – 45,700 versus 22,400 total units.

A Civic Culture That Thinks at the Regional Scale

In 1958 and 1959 the San Francisco Planning and Housing Association, then a 47-year-old organization, divided itself into two groups. One was named Citizens for Regional Recreation and Parks, which was eventually renamed Greenbelt Alliance. The other was named the San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association, with “renewal" later changed to "research." For better or worse, San Francisco made the fateful decision to have a division of labor in which one group focused on protecting the edge of the region, and the other group focused on channeling growth into the urban core.

In Seattle, on the other hand, an organization has been evolving that is devoted to good planning on the regional level, but that addresses the central cities as well. The Cascade Land Conservancy was founded in 1989 and serves as the good-planning organization for five counties: King, Snohomish, Pierce, Kittitas and Mason.

The Cascade Land Conservancy functioned originally as a traditional land conservancy — buying land, managing lands, facilitating the transfer of development rights from rural to urban areas, helping government acquire and protect environmentally critical lands, as well as running a planning consulting practice.

But in order to truly protect the regional landscape, they knew they needed to expand their mission. The Cascade Agenda was the ambitious result — a land-use plan for the region over the next 100 years, addressing urban and suburban growth, the preservation of the agricultural and timber land base, and the protection of ecological assets. The plan assumes the population in the region will double, from 3.5 million to 7 million.

To accommodate this growth while protecting what needs to be protected from change, the plan outlines policy changes at the state and local levels to achieve the 100-year vision.

Notably, the Cascade Agenda specifically promotes well-designed infill development through its City Program. The Seattle portion of the City Program's work is being organized into a relatively new effort known as the Seattle Great City Initiative. It brings together local environmentalists, neighborhood advocates and green-business leaders (including developers) to develop a common agenda to make Seattle a model of economic and environmental sustainability. Its goals includepromoting more housing; transportation policies that favor walking, biking and transit; and more investment in parks and public places. They have a particular emphasis on “green infrastructure” — using private and public investment in the built environment to enhance ecological function and livability. The organization intends to tap into Seattle citizens’ concerns with climate change, sprawl and pollution and make the connection to promoting good urban development. It's too soon to know how the Great City Initiative will evolve, but it is on the map as one of the newest additions to the network of civic planning organizations, of which SPUR is a part.

The Cascade Land Conservancy has made another decision that is quite different from those we have made here: They have decided to redraw the geographic boundaries of their work repeatedly, expanding them to take in the farthest reaches of the Puget Sound urban sprawl and the rural lands that are to be preserved.

In addition to mid-rise construction, Seattle also has experienced in high-rise resident development.

In the Bay Area, a growing percentage of the regional population growth over the next 50 years is actually taking place outside the nine-county official Bay Area. Our regional growth has leapfrogged north, south and especially east into the Central Valley. We are in fact witnessing the emergence of an integrated Northern California megaregion that encompasses the Central Valley between Fresno and Redding, and extends far up into the Sierras.

The same thing is happening in Puget Sound, where the frontiers of sprawl are on the Kitsap Peninsula to the west and the Cascade Range to the east, with sprawl extending north and south as well. But where Greenbelt Alliance has made the strategic decision to stay focused on its core territory of the historic nine Bay Area counties, the Cascade Land Conservancy has decided to work on a broader region defined by its relationship to Puget Sound and the Cascades.

It's important to note that it's not just at the neighborhood and regional level that we have something to learn from Cascadia. Both Oregon and Washington have powerful, effective statewide planning organizations as well, in the form of 1,000 Friends of Oregon and Futurewise (formerly 1,000Friends of Washington). These groups helped create the growth-management frameworks for their states and continue to be the leading partisans for good planning at the state level. No such group has ever managed to gain that level of traction at the state level in California, and this may explain a lot about the state of our state.

The big-picture outcomes — How much does a region sprawl? How much do people have to drive? How economically resilient are communities?— are partly determined by the strategies that social-change organizations use. Somehow,civic culture in Seattle has gotten thoroughly comfortable thinking about local planning issues in a regional context. Does the “culture" in Seattle and the Bay Area shape the different strategies that planning advocacy organizations use? Or is it the different strategies that have, over time, created the planning culture? Maybe the influence runs in both directions.

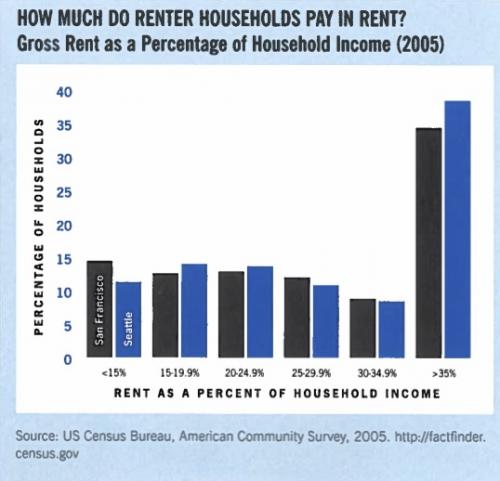

For some renter households, San Francisco is more affordable than Seattle. More than 38 percent of renter-occupied households in Seattle pay more than 35 percent of their household income toward rent compared with 34 percent in San Francisco. In addition, the percent of San Francisco renter households that pay a small fraction of income on rent (<15 percent) is greater in San Francisco than in Seattle (14 percent in S.F. versus 11 percent in Seattle). These differences are due, in part, to high household income in San Francisco and rent control.

Can Neighborhood Planning Think Regionally?

For years, SPUR has criticized the regional planning agencies in the Bay Area for unwillingness to model multiple growth scenarios, the propensity to make infrastructure investments that enable more sprawl, the willingness to build expensive transit systems without transit-supportive land uses, and all the rest. But in recent years, regional planning in the Bay Area has begun to undergo the early beginnings of a renaissance. The Association of Bay Area Governments’ Focusing Our Region project, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission's Regional Rail Plan and the Great Communities Collaborative (a project of four non-profit organizations: the Transportation and Land Use Coalition, Greenbelt Alliance, the Non Profit Housing Association of Northern California and Urban Habitat) are all steps in the right direction. Maybe, optimistically, we can say that regional planning is becoming a little less broken in the Bay Area.

But we have to acknowledge that neighborhood planning is just as broken as regional planning. Nine years into the Better Neighborhoods 2002 Plans, we have essentially one plan nearing the end of its adoption process (Market and Octavia). Asof this writing, we still do not know if the adoption process for Balboa Park will have begun, nor do weknow whether San Francisco will do something truly meaningful to add to housing supply, or the locationof jobs proximate to transit, as a result of a decade of work and millions of dollars invested in the effort.

This is the result of neighborhood planningdone in the absence of real regional planning.Not only do we not have regional planning with any teeth, we don't even have citywide planning anymore. Because of the way our planning process is structured, each neighborhood ends up being allowed to act like an autonomous nation without real connection to the needs of the city or the region.

Seattle has approached the redevelopment of its public housing as mixed-income communities with high-quality design and sustainable innovations.

As a society, we are confronting terrifically difficult problems such as global warming and other emerging forms of environmental destruction. But our democratic process is failing us when it comesto the fundamental questions of land use that determine so much of our species’ impact on the planet. Many of the answers to the environmental problems of our time are contained within the neighborhood planning work we do: This is how we, as a people, decide to occupy the earth. Will we place ourselves into patterns that consume land and require driving for every trip? Or will we create compact neighborhoods in which every person has the ability to walk to local stores and access great transit? Acting as if we can make neighborhood planning decisions in the absence of regionaland global considerations is delusional, in that it allows people to think that the only things they should consider are their personal preferences for the kind of things they would like to see in their neighborhood, as if the accumulation of all of these individual neighborhood choices does not have massive impacts on the region. Neighborhood planning needs to be our method of achieving outcomes that are good for the region (and world), in ways that are appropriate to our bioregionand our culture. Seattle suggests some possible approaches.

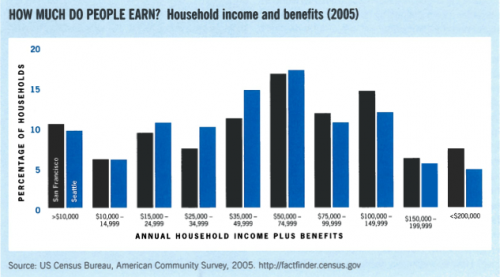

Compared with Seattle, San Francisco has a greater share of its population with high incomes and low incomes. This bifurcated labor market results from higher salaries in some of San Francisco’s basic sectors (like financial services) as well as the presence of a greater share of workers in low wage industries such as hospitality.

But let's conclude on an optimistic note. ABAG is, once again, trying to create a regional jobs/housing allocation process, with teeth, that directs a larger share of the region's growth into already-urbanized areas. This is the highly politicized process in which every Bay Area city fights to be “assigned" as small a number of housing units as possible out of thepredicted total regional growth. For many years, theprocess has followed a predictable path: ABAG staff proposes a relatively progressive formula that would allocate growth targets in a direction of less sprawl — and then the politicians fight to have the staff formulas reversed. And the cities are essentially free to ignore the allocations anyway. In Oregon andWashington, the states have at least some authority over local zoning. Here in California, reformers have never really tried for that, instead hoping that state infrastructure spending would be directed away from sprawl, and would reward communities that meet their housing targets.

ABAG’s latest round of numbers, released in August of this year, increases San Francisco’s annual housing production target to 4,500 units per year (31,200 total between 2007 and 2014), compared with the current target of 3,450. The question, of course, is whether ABAG, MTC, the state, or any entity with resources will actually impose sanctions on transit-rich cities that don’t meet their targets and shift resources to the cities that do meet their targets (and even, potentially, impose sanctions in exurban locations that allow growth to occur in places it shouldn't). Maybe, just maybe, this will be the time that the regionsteps up to provide a context for neighborhood planning. But in the meantime, there is nothing stopping us from doing our own planning work as if we cared about its effects on the region and the world.

For more information

San Francisco Better Neighborhoods Plan

Oregon Land Conservation and Development Commission

Washington's Growth Management Act

Puget Sound Regional Council Vision 2040 Planning Process

Review of the Washington Growth Management Act prepared by the Puget Sound Regional Council

League of Women Voters Analysis of Washington’s Growth Management Act

Futurewise (formerly 1,000 Friends of Washington)

ABAG's Smart Growth FOCUS project

ABAG's 2007 Regional Housing Needs Allocation

As of fall 2012, the Cascade Land Conservancy is now Forterra