Is there any other city with so many plaques paying homage to planning? On buildings and in plazas one reads about Portland’s 1972 downtown plan, under the heading, “We Planned, It Worked.”

Most planners see the Portland region as one that has tackled the problem of suburban sprawl more successfully than any other region in the United States. Less attention has been given to the renaissance of Portland under that program. Since the early 1970s, a number of visionary leaders and civic movements have built a legal and institutional framework that today guides the development of both the region and the city in a way that is different from anything else in the country.

There are three main actors in governance—the state of Oregon, Portland Metro, and the city of Portland—all superstars in the opinion of this author. There is also a host of supporting actors, including highly visible heroes like Governor Tom McCall, Portland’s then-Mayor Neil Goldschmidt; the group 1,000 Friends of Oregon, and a few less visible and less recognizable villains.

Unlike similar efforts at land use reform in California and some other states, where interest groups are often at odds over the best direction for state, regional, and local planning, the drama in Portland has largely been positive and enlightening as it unfolded on the legislative stage with a backdrop of an already livable region and city—it was a feel-good smash hit from the start in the view of urban reformers. Unfortunately, the script for the next act—which picks up after the plot twist of the passage of Measure 37 in November 2004—remains unclear but looks ominous.

Planning by the State Government

In 1969, then-Governor Tom McCall famously led the effort to enact Oregon’s Senate Bill 100, creating a statewide planning program and its administering agency, the Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC). It was founded on a set of 19 statewide planning goals conveying state policy on land use and related topics, such as housing, recreation, and natural resources.

Oregon’s statewide goals are achievable mainly by local comprehensive planning, with state law requiring each city and county to adopt a comprehensive plan and the regulations to put it into effect. LCDC adopts and amends the state land-use goals and implements what are called rules (or administrative guidelines) to promote local-plan compliance with the goals, coordinates state and local planning, and manages the coastal-zone program. Given the scope and potency of LCDC, Oregon has never had to enact a state environmental protection act like California’s Environmental Quality Act (CEQA); one would only confuse a smoothly operating process.

But many Oregon counties, particularly those in the eastern part of the state, have rankled under what they considered draconian rulings handed down from Salem, and there have been attempts at LCDC abolition. To some observers, Measure 37 constitutes de facto abolition, but the last line of the script has yet to be written. (See Oregon's November Surprise; February 2005.)

Since local comprehensive plans must be consistent with statewide planning goals, the plans are initially and then periodically reviewed for consistency by LCDC. When LCDC officially approves a local government’s plan, it is said to be “acknowledged” (rather than “approved,” “accepted,” or any other word connoting state authority). It then becomes the controlling instrument for land use in the area.

Planning by the Regional Government

LCDC may have provided the foundation, but Portland Metro set the tone for the effective planning that has long been a Portland hallmark. Metro was established in 1978 as a metropolitan planning agency. It replaced a conventional council of governments, but rather than responding defensively to LCDC, it responded boldly and affirmatively with the distinctive mission of enhancing urban livability. The state did not grant Metro the power to prepare a comprehensive regional plan and compel each locality to adhere to it. Instead Metro was allowed to prepare regional functional plans and require changes in its constituent localities’ comprehensive plans to make them consistent with those functional plans—a subtle but politically necessary distinction. In home-rule-dominated California, such power granted to a regional entity is unheard of.

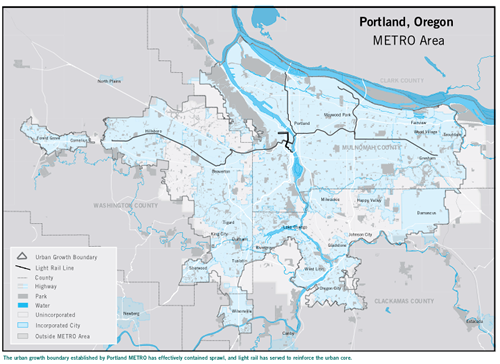

The state recognized the potency of Metro and gave it the responsibility for defining the urban growth boundary for all of the region’s 24 cities and the parts of the three counties within its boundaries, rather than having those jurisdictions do it individually. This had the effect of making Metro the key agency in the process of defining development character and location. And it has carried out its role with a vigor suggesting it is willing to go beyond state mandates.

Fig. 1: METRO's sizeable metropolitan planning region: click image for full-size map (pdf format).

The Region’s 2040 Growth Concept Blueprint

In the late 1980s, a set of regional growth management objectives, a new metropolitan charter of governance, and a regional land information system all highlighted the need for a regional visioning process, the next step toward a true regional plan. This visioning was to reexamine the urban growth boundary (then in effect for over a decade); formulate a new regional transportation scheme, especially for transit; identify a hierarchy of places ranging from downtown Portland to existing towns and new regional centers; and define a system of open spaces.

The resulting 2040 Growth Concept , adopted in 1995, relied on citizen involvement leading to what has now come to be known in some planning circles as Smart Growth policies: protect the existing urban growth boundary area (projected to increase by only seven percent by 2040), reduce vehicular traffic, encourage transit use, foster pedestrian movement, retain existing open spaces, and, perhaps most importantly, increase densities inside the boundary.

This program provided the blueprint that was needed in order to translate the concept into the Regional Framework Plan of 1997, with which all the region’s local plans now had to be consistent. It also continued the policies that have profoundly influenced development in Portland to this day.

The Downtown Plan

Clearly, Downtown Portland is the glowing centerpiece of planning progress in the metropolis. On typical weekends, thousands assemble for a host of activities, most people using transit for access to this vibrant setting. The plan that was instrumental in making this happen was the Portland downtown plan. Before the 1960s there had been few signs of city improvement downtown. The catalyst for change in that was the leadership of the forward-looking mayor (and later governor), Neil Goldschmidt, who helped fend off competition from a regional supermall, rescue a bankrupt bus company, and prevent large-scale clearance of older historic neighborhoods by redevelopment. Goldschmidt mobilized talented professionals and fostered adoption of the first downtown plan in 1972. It included replacement of a riverfront expressway with parks; offered high-density retail corridors, and promoted transit across downtown; established a university district and other historic districts; and fostered higher-density housing.

The plan called for a downtown bus mall to speed service and allow transfer to other lines, thus tying the downtown and the region together along a north-south axis. The downtown bus mall today seems like a foreign and somewhat disruptive urban element, but it still works well as a transportation artery. With the addition of light rail, first from the east and later the west, both crossing downtown, there was a notable reduction of auto commuting, down to around 50 percent of employees. In 1988, the city adopted a Central City Plan, retaining the focus on urban design, subdistricts, and other elements to make the Central City more livable and walkable.

Other Planning by the City

Curiously, forward-looking Portland continues to operate under a relatively archaic form of government—the use of individual elected officials, including the Mayor and Council members, to oversee specific “bureaus.” The Bureau of Planning, not surprisingly, is fortunate in having the Mayor as its “overseer” (and sometimes its champion), allowing it to pursue enlightened policies. It is now formulating an infill design code for medium-density residential development, making environmental code improvements, formulating two area plans, and devising policies for Willamette River improvement. Of course, the bureau continues to monitor the comprehensive plan, the downtown plan, and historic-preservation programs as well.

The Portland Development Commission (PDC) is the city’s redevelopment agency, also directly overseen by the Mayor. Like most redevelopment agencies, it has changed both its focus and its programs over the last few decades to be more responsive and sensitive to project-area context. Its most prominent urban-renewal areas are in the downtown: the River District, Waterfront, and South Park Blocks. Just northwest of downtown, the Pearl District has sprung up in an old industrial/warehouse area, including the brewery blocks, helped by the loft and condominium boom.

In 1994, the River District Housing Implementation Strategy was adopted by the City Council. This called for 5,000 new housing units at an average density of 100 units per acre. It also mandated a mix of new housing, meeting the income demographics of the city.

The Downtown Waterfront Urban Renewal Area is one of Portland’s most successful examples of urban renewal and tax-increment financing. Since the project area was delineated in 1974, the assessed land values in the area have increased at an average of about ten percent per year. To continue strengthening Downtown’s role as the regional center of finance, trade, education, culture, retailing, and governmental services, PDC facilitates public-private partnerships. This has led to McCall Waterfront Park, a rehabilitated Union Station, Pioneer Park, and other attractions.

The Park Blocks, running from north to south through the center of downtown, provide natural beauty in its heart. The South Park Blocks Urban Renewal Area, launched in 1985, includes several neighborhoods: the University District, the Cultural District, and the West End. These subareas include significant historic buildings, cultural attractions, and green spaces. The University District is home to Portland State University (PSU); the Cultural District includes the Portland Art Museum, Schnitzer Concert Hall, and the Performing Arts Center; and the West End has seen a recent increase in mixed-income, mixed-use housing.

The Portland Effect

The 2040 Growth Concept program of the 1980s unleashed the full power of public participation, offered a “visioning” process in the most literal sense of the word—whereby citizens could actually see what the future could bring— by offering visual images to a welcoming audience. That audience is at the heart of the success of the city and its region. Continuing civic engagement in Portland is routine, not the startling phenomenon it is elsewhere—offering, for example, a locally homegrown radio station focusing on civic affairs, a civic membership club that has been meeting for almost 90 years and publishes a weekly bulletin, and a metropolitan daily paper that has been known to have headlines on rezonings.

Hence top billing in the ongoing drama on planning in Portland, must go, not to any agency or official but to the citizens of that city and its region, whose steadfast involvement in local and metropolitan affairs makes the story of Portland unique, instructive, and uplifting.