I’m a city mom with a city kid. We meet other families at local playgrounds in corner parks adjacent to bustling streets. My son can nap through whooping car alarms while his stroller bumps over the sidewalks of the Mission. We’re here for lots of reasons, but they all originate with a straightforward love of the city—urbanity, choice, diversity, and change—a feeling of aliveness. We got to eat take-out Burmese at Jonah’s one-year birthday party. Our immediate neighbors are Chinese, Italian, and Mexican. My husband and I can just walk around the corner to get a drink when our friends come to baby-sit.

It’s a gift to raise our child in San Francisco. I am grateful to be able to do it. But it can be hard too. I worry about our city’s schools; back in Boston, both my parents are public school teachers and I’d like to send my son to public school here. I want Jonah to be able to ride his bike around San Francisco, but the traffic scares me. I am desperate for more bike lanes to be put in place before he is ready to ride around on his own. It’s also expensive to live here and we struggle to pay our mortgage each month.

It’s more than worth it to me, though. This is where I want to be.

Jonah David Sullivan Metcalf has lived in San Francisco since 2003, and enjoys it very much.

The Housing War and its Casualties

As the mother of a kid being raised in San Francisco, I have a vital stake in the way we plan for our city’s future. If he wants to, I hope my son can afford to live here someday—and I want to be able to stay here, too, as I get older.

I don’t know if the “pro-family” planning agenda is any different than the regular “good planning” agenda: I care about the schools and the parks and what it’s like to take a walk and how easy it is to run errands. But as I watch my friends with kids struggle along with me to make everything work in San Francisco, I have to admit it’s the cost of housing that worries me the most. I observe our civic debates about planning and development through the lens of these concerns. Should a street be up-zoned or stay the way it is? Should a housing development be approved or rejected? Should a law be passed to encourage in-law apartments or should the city discourage them? What should the General Plan say about the balance between preservation and change in San Francisco?

Observing my favorite San Francisco neighborhoods (North Beach, the Tendernob, parts of the Mission), makes me think that many of the most controversial proposals—to increase densities, to reduce parking— will improve neighborhoods for families. Increasing the housing supply near transit (especially relatively affordable housing like in-laws) and encouraging the use of transit over driving are important first steps towards a family-friendly city because families thrive in walkable urban villages where services, shopping, and transit are easily accessed on foot. And if the built environment supports a “sustainable” lifestyle, individuals will freely choose to do what is also best for the entire city. That’s part of the reason why I started City CarShare—to give people a practical, fun option to live car-free without having to sacrifice any quality of life. But I’ve heard some people stand up in the name of “families” to criticize these ideas. I’d like to explore the arguments I’ve heard and offer a different perspective.

Who Decides What's Best for Families?

Some of the arguments against new housing and increased development that I’ve encountered include:

1. People who want more housing and higher densities are anti-family.

2. Families cannot or do not want to live in apartment buildings.

3. Building more parking is good for families because it makes driving easier.

None of these arguments are true, in my experience, and here is why:

1. Densification of San Francisco is the only way to improve our city for families. Density is a bad word among many of the self-proclaimed neighborhood leaders in San Francisco, but in practice everyone seems to like it just fine. Most San Franciscans love to walk to meet friends for brunch; they love obscure film festivals, ethnic groceries, and other cultural amenities that can only exist when they are supported by a high local concentration of people. And property values in the highest-density neighborhoods are always higher than in the rest of the city, suggesting that lots of people want to live in those neighborhoods. Despite all of the incredible things in the Mission, I wish that my immediate neighborhood had a fish store, fresh bagels, or a place to buy plants. But of course, the conveniences of neighborhood shopping are directly dependent on how many people live within walking distance We need to add more people to support more city amenities. If my neighborhood gets healthier, it will not get less dense—more people will move here and in turn support services that the rest of us want.

The other reason the pro-family agenda means more density is that it’s the only way to start bringing down housing costs. Families need the supply/demand imbalance to be remedied, end of story. If you’re not rich, but you have kids, you need to be able to pay the rent or the mortgage, and still have time to be with your family. This boils down to more housing, both below market rate and middle of the market. To work best, the city needs housing affordable to all families—so that wage-earners don’t have to commute into the city from points east to their jobs. By definition, that means increasing densities—and I, for one, hope the Planning Department and our elected officials will make that their priority.

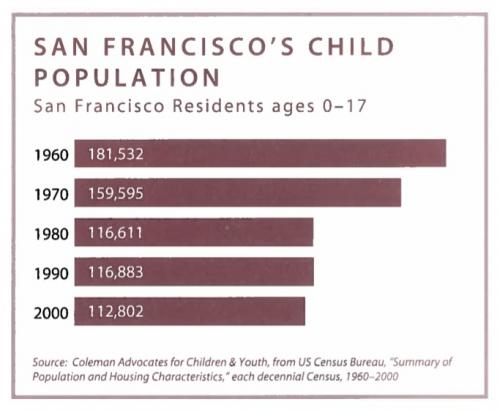

One of the saddest indicators of San Francisco's high cost of housing is the decline in the number of children who live in the city. Since 1960, the number of residents under age 18 has fallen by almost 40%.

2. Many families will happily live in apartment buildings. We’ve traveled in the last year to Vancouver, Boston, and New York City. I can say unequivocally that many families will choose to live in well-designed apartment buildings in very urban neighborhoods if they get the chance. My own family would love to live in a tall building as we did in Seattle years ago—it always made me feel safe, and I think it is romantic to have a view. Many families do this in all the most “livable” cities in the world.

On our trip to New York, I visited friends who live on the Lower East Side (living on the fifth floor with a six year old), on the ninth floor on the Upper West Side (where a single mom had raised a boy and girl, now 25 and 28), and a couple about to have a baby in their sixth-floor walk-up in Greenwich Village. We walked to meet other friend/parents at a breathtaking park on a pier jutting into the East River just one block from Greenwich Street. The park was teeming with toddlers, all of whom obviously lived in the mid-rise neighborhood and had walked with their parents to the park. Families were also arriving by bicycle—even crossing the West Side Highway on traffic-calmed walkways. I’ve never seen any park even half as nice in San Francisco for kids—and I am a true aficionado. This park had unique, artistic climbing structures, sunshade sails, even a little trickle of water simulating a creek meandering around—complete with brass starfish and crabs scattered in the channel. In an hour I heard Spanish, Hebrew, German, and French being spoken, and saw moms in saris and dads in suits and some in shorts—and everyone was chatting with one another. I submit that it is the close proximity of this diversity of city dwellers that creates the conditions for such an amenity. The density brought by apartment living created this amazing public space and thriving community in the big city.

I was on the SPUR trip to Vancouver recently and learned that apartments are more affordable for families there, (hovering around 50% of our rental and purchase prices). This is mostly because housing is built generously. All during the boom of the 1990s, housing prices actually went down in Vancouver they were building so many high-rise apartments. At the same time, the population of kids went up, creating new demands for schools. They essentially solved their supply/demand problem, making it possible for families to live downtown. One neighborhood I visited had put high-rises next to a little water park. Kids were splashing in the water fountains while their watchful parents lounged at a nearby cafe—all within a few steps of Concord Pacific Place, a large residential development. Within a five-minute walk were a new grocery store, various shops, a community center in an old railway station, parks, and many other apartment buildings. It was real urban living, just-built, and safe, cheap, diverse, clean, unique, and fun. It was really done right, and I’d call it perfect for families.

But finally, it’s definitely true that some families don’t want to live in an apartment building, no matter how nice; they want a house with a yard. Still, that dream is easier for them to realize when the pressure for housing is reduced and the costs come down for everyone. Building housing at all levels makes all of our dreams more affordable.

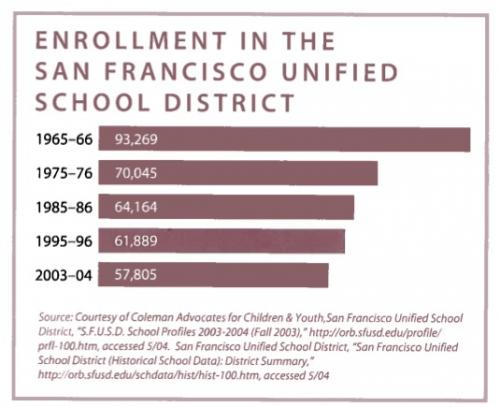

Roughly two-thirds of school-age kids are enrolled in the San Francisco Unified School District. This number has remained relatively constant over the years, due perhaps to San Francisco's tradition of Catholic schools. The decline in public school enrollment numbers parallels the overall decline in the population of children.

3. Planning for the continued dominance of the automobile is what makes cities so dangerous for kids. It’s true that with a kid, I find I need to drive more. But the reasons are that (a) I can’t afford to live in a more walkable, higher-density neighborhood; and (b) the alternative transportation systems are still too underdeveloped in San Francisco. Without being “anti-car,” and while recognizing that families will probably tend to have higher car-ownership rates than people without kids, it just seems to me that all of our efforts should be going in the direction of improving alternatives to the automobile. Making Muni better and making safe bike paths through every neighborhood should be the priorities for people who care about kids’ safety in the city. Adding parking is not the solution. That locks us into the current state of gridlock, where the traffic keeps Muni from working, where there’s so much congestion that car drivers are running over bicyclists and pedestrians, and where children are especially vulnerable.

When a family considers a trip (grocery store, movies, playground) the first question is, “How will we get there?” If you own a car, there is an extremely strong added incentive to drive if you know you can park for free when you arrive. When cities discourage driving, people walk or take transit. It’s really this simple. For examples, we can look to any city in the world—the places where common sense dictates that one “cannot“ own a car (Boston, New York, Paris) are the most walkable, enjoyable places to be. No one really admires the quality of life in cities dominated by cars like Denver, Detroit, or Los Angeles. Without punishing people who own cars today or who drive, our plans for the future should be moving us in a transit-oriented direction where more people can get around conveniently without a car.

Protecting the Neighborhood to Death

Supporters of housing often get accused of being against historic preservation or out to destroy neighborhood character. But it’s not all one or the other. The vast majority of the city’s buildings are going to remain just as they are. And obviously the truly historically significant and especially beautiful structures should be saved, offering future generations the chance to experience the layers of history in real life. As a parks activist, I’ve been involved in many fights to protect valuable partsof our city’s open space. But in some places, I think it’s important that we move strongly in the direction of embracing new development.

The idea that nothing in a neighborhood should change is a terrible lesson for kids. Life is change, it can be good, and your home can get better. One of the great lessons of the historic preservation movement is that every generation has contributed its own ideas about what makes a good city, by building in a way that reflected its aspirations. Our generation is going to do the same thing, and later, so will Jonah’s generation. Stopping change will make San Francisco a sterile place, a mausoleum. That is not the kind of environment I want to raise my child in. That is not what cities are about.

In the name of “protecting neighborhood character,” I have watched some San Franciscans fight to kill affordable housing for school teachers, senior housing, shelters for runaway teens, parks improvements for children, bike lanes, transit improvements, and neighborhood-serving retail. This is utterly shameful. Opponents say, “I’m not against affordable housing and transit, just not in my neighborhood—it’s not ‘appropriate’ here for the character of our area. Put it in Hunter’s Point or someplace else.” Not a generous lesson to teach children: that housing our citizens—our community—is someone else’s problem because “we” were here first, and newcomers don’t belong.

There has to be a better way to plan our city’s future. And I believe the truth is, when we accept or encourage new housing in our neighborhoods—if it is planned and designed right—it will improve our quality of life.

Shaping the Change as it Comes

San Francisco is a city. Some critics of the more visionary planning ideas seem, to my mind, to want to impose a more suburban ideal, with a focus on limiting new housing, building more parking, and refusing to plan for newcomers. To me, they are disingenuous when they claim to be the only ones fighting for families. I say that it is contested ground—that I, as a housing and transit advocate, am fighting for them too.

I have this daydream of a future San Francisco where my little son could someday be sent out to buy the bread for dinner like children in movies set in Paris. Or ride his bicycle to a music lesson or basketball game. He deserves the experience of discovering the magic of this city on his own, as he grows up, not just watching it pass in a blur from the backseat of a car.

I am sure we would all agree that the ultimate goal is to have soulful, vital places in our city where families can live and thrive. We need neighborhoods safe for children and adults alike, and streets that are free of dangerous congestion. The best and most effective way to do this is to grow our city, intelligently.

The author with Jonah.