San Francisco is required to plan for at least 82,069 new units of housing by 2031 to address the local housing shortage and comply with state obligations. The city’s proposed Family Zoning Plan would locate many of those homes in west side neighborhoods that haven’t see much growth in recent decades.

What would a population increase like this mean for traffic and mobility in this part of the city? To find out, SPUR delved into local transportation data and made some surprising discoveries about traffic and commute patterns. Namely, due to the area’s high number of schools and jobs, fully one third of all work and school trips in San Francisco end in the west side, and many of those who live in these neighborhoods already live car-light lifestyles. What if more people who work and go to school on the west side could afford to live there? Is it possible that traffic congestion could get better — not worse? One thing is clear: the plan’s success will hinge on the imperative to fund Muni for the benefit of both current and future residents.

The Family Zoning Plan

To reach the state-mandated goal of 82,069 new homes, San Francisco must update its zoning rules to allow 36,200 new housing units to be built by 2031 (in addition to 58,000 units already in the permitting and construction pipeline). This plan must be fully adopted before January 2026 in order to stay in compliance with state regulators. The latest revision of the Family Rezoning Plan, announced in June, would, if passed, achieve this through height and density increases throughout most of the city’s western and northern neighborhoods. The cluster of neighborhoods subject to the rezoning plan has, since the 1970s, been overwhelmingly zoned for single-family homes and other very low density housing. Over the last 20 years, just 10 percent of the city’s new housing units have been built there, effectively cutting off these amenity-rich neighborhoods to those who can’t afford to buy a single-family home. The rezoning plan overlaps almost entirely with an area of San Francisco called the housing opportunity area (HOA), which is defined as the combined census tracts classified as “well-resourced neighborhoods” in the city’s 2022 Housing Element.

The Housing Opportunity Area

The Family Rezoning Plan area overlaps closely with the “housing opportunity area,” the census tracts that the 2022 Housing Element classifies as “well-resourced neighborhoods.”

Source: SPUR

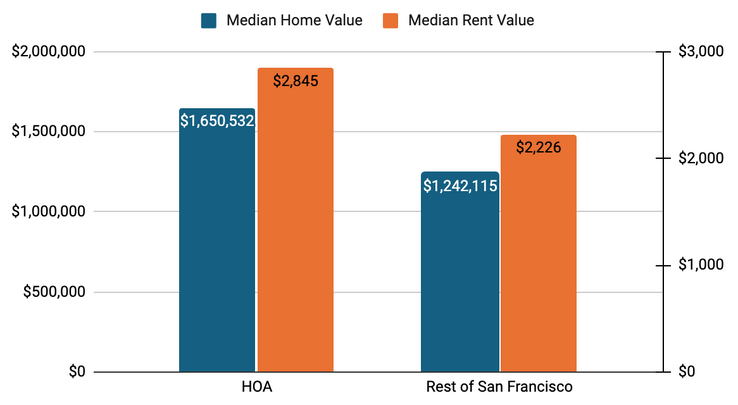

Median Rent and Home Values in the Housing Opportunity Area Compared to the Rest of San Francisco

Exclusionary zoning practices of the last 50-plus years have contributed to the HOA being significantly more expensive than the rest of San Francisco.

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, 2023

This exclusion matters. The Family Zoning Plan is about more than affordability or compliance with state regulations; it’s also about making it possible for anyone to live near the places they want to go and reducing car dependency in the city. Under the city’s current zoning map, housing has been kept out of job- and school-rich neighborhoods in the west side. But a full third of all work and school trips in San Francisco end in the HOA, where major institutions such as the UCSF Parnassus Medical Center, San Francisco State University, City College, University of San Francisco, Stonestown Galleria, the Presidio, and many K-12 public and private schools draw tens of thousands of students and workers every day. Proximity to work is the biggest determinant of where people choose to live (besides cost), and distance to work is one of the strongest predictors of how much people drive. The housing types proposed in the Family Zoning Plan — including duplexes, fourplexes, and taller apartment buildings near transit in high-resource neighborhoods — align directly with the recommendations in SPUR’s Regional Strategy. Our research shows that legalizing dense and diverse housing types in transit-connected, amenity-rich neighborhoods would allow residents to meet most daily needs without a car, reducing household costs and improving public health and well-being.

Transportation Patterns on San Francisco’s West Side

To better understand how land use and travel might change under the Family Zoning Plan, we analyzed current trip patterns in the HOA. (Note: For this analysis we chose to include the Presidio as an extension of the HOA because it is a jobs and residential hub fully surrounded by the HOA. We also included the Stonestown and San Francisco State University census tract in the analysis for similar reasons.) We looked at the primary transportation mode used for the trip (automobile, transit, bike, etc.), and whether those travelers drive for routine, everyday trips. These measures reflect the structural reasons people drive, including how far they live from their destinations and whether alternatives like transit or walking are viable. Our analysis focused on the following questions: What are the existing travel choices for people who work or go to school in the HOA? How are these travel choices different if you do or don’t live in the HOA? How might the zoning plan realistically shift people’s travel behavior by allowing more of them to live closer to where they already go? To answer these questions we turned to Replica, a trip modeling platform with detailed origin, destination, and trip mode data.

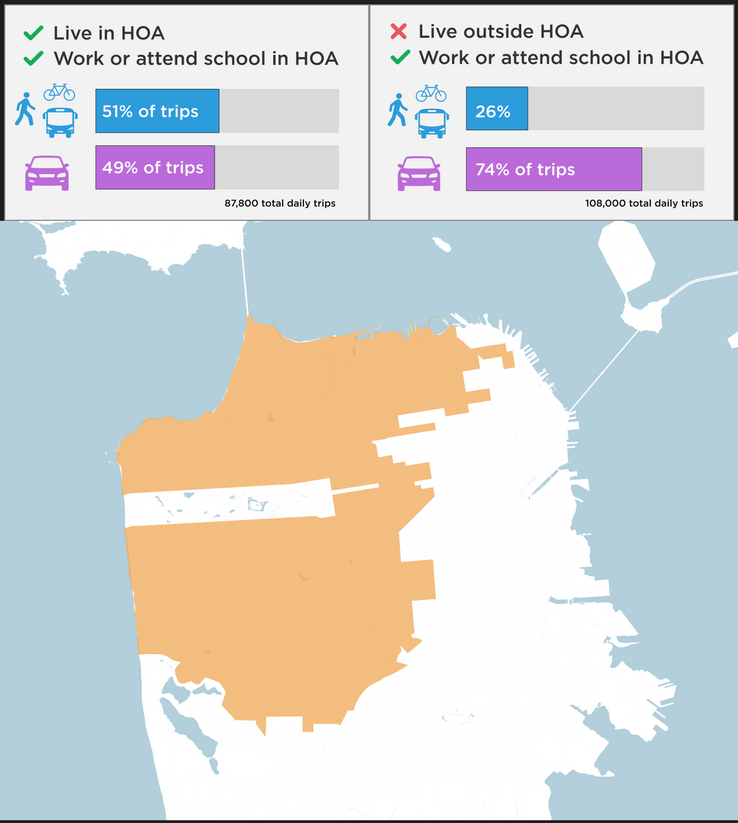

We found that, today, 46% of all daily trips that end in the HOA are made by non-HOA residents. In a typical neighborhood, one would expect most trips to be generated internally, reflecting strong alignment between where people live and where they work or study. The result of the HOA’s imbalance is a travel pattern that leans heavily on cars. Each day, about 1.26 million total trips end in the HOA, and 599,000 of them originate externally, with roughly 74% of those trips made by car. However, for trips entirely within the HOA, only 49% are made by car. Nearly 60% of all car trips ending in the HOA are made by people who do not live there.

The same pattern shows up when focusing on commute trips. We found that fewer than half of the people who work or study in the HOA actually live there, and that 54% of all daily commutes to the HOA start somewhere else. There are 113,000 commute trips into the HOA each day, and three out of four of those commuters drive. Among the 94,000 trips made by people who both live and work or study in the HOA, less than half of those people choose to drive. Instead, they’re far more likely to commute by active modes (walking, biking, and public transit). These trip patterns show that the HOA is not a car-dependent place. It is in fact quite walkable … for those who can afford to live there. A majority of all trips that both start and end within the area are made by walking, biking, or public transit. For errands, shopping, and other non-work trips, that number is even higher.

Trips Into the Housing Opportunity Area

On an average weekday, nearly 200,000 trips are made to work or school in the HOA. The majority of those trips are made by people who live outside the HOA and commute in. Those who commute into the HOA for work or school take a car for 74% of trips. However, for people who live inside the HOA, more than half of trips to work or school are made by walking, bicycling, or taking transit.

Source: SPUR image based on Replica data

The built environment, and the land uses within it, shape travel choices. The westside neighborhoods already have a walkable street grid, small neighborhood commercial districts, and strong access to transit. The Family Zoning Plan builds on those patterns, allowing denser, multiuse buildings on every corner parcel and taller mixed-use buildings along all transit corridors, making it easier for more residents to reach daily services on foot or by bus. And it targets growth along transit-rich corridors like Geary Boulevard, Judah Street, and California Street, where people are already less likely to drive. In the Richmond District, for example, bus routes like the 38 Geary, 5 Fulton, and 1 California carry a combined 65 percent of the district’s total Muni ridership. In the Sunset District, much of the rezoning is concentrated along the N Judah, the most heavily used light-rail line in the city. This zoning plan is not speculative planning; it is built around routes already moving tens of thousands of riders each day.

Over time, the Family Zoning Plan has the potential to reduce car dependency by allowing more people to live in neighborhoods that already support car-light living, in large part due to their proximity to daily destinations like schools and jobs. By allowing more people to live close to where they want to go, improving access to frequent transit, limiting off-street parking, and encouraging flexible commercial uses on more properties, the plan creates conditions that give people the option to drive less, especially for daily trips.

What Happens If the Plan Is Not Adopted?

If San Francisco does not adopt a compliant rezoning plan before January 2026, the city risks being decertified by the state and losing much of its local control around zoning and permitting. If this happens, the city would be subject to the “builder’s remedy,” a state law that forces a city to approve any housing project, including those far in excess of local height and density limits. This process results in delays on permitting for home improvement projects. It would also place hundreds of millions of dollars in state funds on hold, blocking critical investment on priorities including affordable housing and public transit. Demographers and statisticians at the California Department of Housing and Community Development have already calculated that there will be demand for 82,000 more housing units over the next five years, and they will get built — whether through the Family Zoning Plan or through decertification and the builder’s remedy. Will the location of that new housing reinforce car-light trip patterns already prevalent among residents? Or will it lead to longer commutes, more car dependency, gridlock, and higher household transportation costs? The Family Zoning Plan, as it stands now, is the best option San Franciscans have to reduce driving and car-dependency as the city’s population and local economy grow.

Why Muni Funding Is Critical to the Plan's Success

These trip patterns will only be possible with a fully funded Muni that supports frequent and predictable transit. Muni currently faces an operating deficit of over $300 million. If proper funding is not secured, city officials have warned that entire bus lines could face suspension of service, and surviving bus lines could suffer service reductions of 50% or higher. Many of these lines are already overcrowded — and many are the same lines that will be most critical to supporting new westside density.

Key transit lines at risk of significant service reductions without adequate funding include:

- 1 California: Already the agency’s most overcrowded Muni bus line, with 15% of peak-hour trips experiencing overcrowding, the 1 is at risk of complete suspension.

- 38 Geary and 5 Fulton: Both connect the Outer Richmond to downtown, rank among the top 10 most overcrowded bus lines, and face potential service cuts of more than 50%.

- N Judah: The city’s most heavily used light rail line, connecting the Outer Sunset to downtown, also faces potential major service reductions.

- 28 19th Avenue: The north-south connection for the HOA, connecting multiple upzoned corridors including Stonestown, currently faces upwards of 9% overcrowding, and at risk of a 50% service cut.

These lines directly serve corridors targeted for rezoning — areas where current residents demonstrate high transit use. If frequent and reliable Muni service is compromised and Muni is no longer a viable alternative to driving, new residents are far likelier to resort to private vehicle use. This undermines the city’s efforts to reduce car dependency and improve public health and well-being.

Proper Muni funding is vital for San Francisco to achieve its environmental and economic goals. Currently, Senate Bill 63, which will establish a Bay Area-wide taxing district with the power to place tax initiatives on the ballot to fund transit, is making its way through the state senate. Though this bill will provide some funding to Muni, it is a regional measure and will not provide the money necessary to fully close Muni’s deficit. A local San Francisco measure will likely appear alongside the regional measure on the November 2026 ballot to bridge the gap. The failure of either of these measures at the ballot box will spell doom not just for the region’s current residents but for the hundreds of thousands of new residents who will live in the Bay Area in coming years.

How San Franciscans Can Help

The Family Zoning Plan will be up for a final adoption vote before the San Francisco Planning Commission on September 11, and will then go to the Board of Supervisors for approval. If you live in San Francisco and care about this issue, showing up and making your voice heard will go a long way toward helping adopt this plan and securing a place for all San Francisco residents, current and future. For Muni funding, call your state senator and relay your support for SB 63, and be sure to advocate and vote for both of the transit funding measures when they appear on the ballot in November 2026.