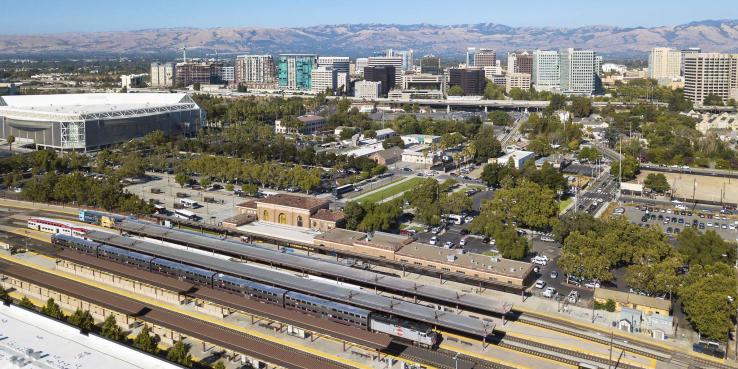

Decades from now, will San Jose’s redesigned Diridon Station be a hub of activity that teems with mobility options and plays a central role in the city and the region — or will it be a missed opportunity?

Last month, SPUR convened national and international experts in San Jose to share best practices for planning and building world-class transit stations and active neighborhoods around them. City officials, legislators, civic groups, transportation and city planning experts, and transit agency executives, directors and staff came together to help develop the vision for the future Diridon Station and to consider — at the beginning of the visioning process — the legacy that, decision by decision, leaders will create for the project.

The symposium was part of SPUR’s work supporting the build out of California’s high-speed rail system and, specifically, our multi-year initiative Next Stop: Diridon. The goal of this work is to transform San Jose’s central station into a world-class transportation hub that connects people seamlessly across the region and the state. The timing of the symposium coincided with the initiation of a partnership between the City of San Jose, the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA), Caltrain and the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) to develop a concept plan for the integration of existing and future transit services at a new, expanded Diridon Station.

Building upon the success of our 2017 study tour, which took a delegation of South Bay leaders to four high-speed rail station cities in Europe, the Transit-Centered Cities Symposium featured speakers from the Netherlands, France, Great Britain, Denver, Los Angeles and San Francisco. The speakers provided insights about the role of transit stations in a changing mobility ecosystem, how land use and urban design decisions affect the success of the transit services, and how leadership at all levels is critical to achieving a world-class transit network.

Here’s a summary of the lessons they offered. Their presentations and videos are available at the end of this article.

The Central Role of the Station

We’ve all experienced the rapid and continuous innovations happening in transportation today. While we don’t know which ones will endure, we do know that transit of the future must be flexible enough to serve the needs of users and must integrate with whatever may come next. As new technologies develop, we believe that a transit station must play a central role in a city, serve as a hub for a variety of mobility options and draw people out of their personal cars. The following principles address the planning and design of multimodal hubs — stations where many different modes of travel connect.

Start by integrating mobility services and transit systems.

European countries are known for their integrated transit systems. People there are accustomed to using one transit pass to move across a region; riders don’t have to worry about how many different mobility services and operators make the system work. At multimodal hubs, decision-makers have worked to create a seamless experience for travelers.

Etienne Riot, head of innovation and research at the design lab of AREP, a subsidiary of the French National Railway, emphasized the importance of removing all barriers, starting at the earliest stages of the planning process. This includes both physical barriers, like passing through different gates for different transit services, and intangible ones, such as coordinating transit schedules, ticketing and information.

Choose a design that balances ambition and simplicity.

What do we mean by “world-class” stations? Those that connect local, regional and sometimes international services, becoming landmarks for their neighborhood, their city and even their region. Finding the right balance between ambition and simplicity is critical to making stations of this scale efficient and usable.

Daniel Jongtien, architect partner at Benthem Crouwel, presented the ideas behind the complicated redevelopment of Amsterdam Centraal Station. These include opening the station so that it faces multiple sides of the city; removing car traffic from the ground level to open the space for light rail, walking and biking; elevating the bus deck to the same level as the train platforms (which was particularly bold considering how often the bus system is dismissed) and providing natural light at multiple levels of the station. Utrecht and Rotterdam’s central stations are other examples of ambitious but highly usable stations.

Enhance the user experience — today and tomorrow.

To get people out of their (or others’) cars, world-class multimodal hubs make transit the obvious choice by offering a great user experience and by simply providing people with better ways to move across the city, the region and country.

In order to create this kind of experience, it is imperative for transit agencies and state and local governments to work together to put the user at the forefront during the planning phase and strip away any barriers that may undermine people’s ability to take advantage of transit services.

Even though a reimagined Diridon Station will take years to build, there are immediate actions that can improve the experience of riders today. The partner agencies in the concept plan and Diridon’s rail operators can collaboratively invest in pop-up stores, food trucks, innovative furniture and public art to make current riders’ time at Diridon more pleasant. Low-cost improvements can attract new transit users and function as a method for gathering community feedback during the visioning and planning phases.

Consider long-term uses and costs during station planning.

All major transit projects require time and significant investment to plan and construct. In the meantime, uses and technologies evolve at a fast past. In order for stations, multimodal hubs and transit stops to serve people’s need today as well as in the future, their planning has to be flexible — including spaces that can adapt to different uses over time without the need to be re-designed or heavily re-invested in.

Transit leaders and planners must also consider future maintenance and operations costs during station planning. Keeping multimodal stations easy to maintain and operate is critical to their ongoing success and functionality.

The Transit-Oriented Communities team at Los Angeles Metro developed a Systemwide Station Design framework to guide planning and design of future bus stops and rail stations. Georgia Sheridan, the team’s senior manager, presented examples of the framework’s recommendations, such as a selection of materials that can support high foot traffic and are easy to clean, reducing maintenance costs. The benefits of the framework are twofold. First, it guarantees cohesive design across the system, allowing riders to orient themselves easily, even in stations they’ve never visited before. Second, it eases the decision-making process by providing a checklist of elements that stops and stations should include or avoid.

Land Use and Urban Design in the Station Area

While the definition of great urban design can certainly be argued over, several lessons from other station cities are worth considering as the visioning process for Diridon Station begins. These principles address land uses around stations and the revenues they can generate for future improvements to the public realm.

Enforce strict pedestrian-oriented development and urban design standards.

A number of historic commuter rail stations and transit centers in the United States have been designed in a way that disconnects neighborhoods: Facing the city on only one side, they’re often surrounded by vacant parking lots and car-oriented infrastructure on the other three. This has disincentivized people from walking and biking and has not helped increase transit ridership. This was the case of San Francisco’s old Transbay Terminal, and it is still the case for Diridon Station.

The plan for a new Transbay Transit Center started out as a large parking lot covered by a bus terminal. But when San Francisco voters approved a proposal to bring Caltrain downtown, the vision expanded to become a multimodal hub connecting walkable neighborhoods. The City and County of San Francisco, along with the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, conceived a plan to expand the financial district south of the terminal and add housing to create a 24-hour neighborhood. The city’s first move was to increase building height limits across the entire district to maximize new development, which research has shown is the only way to support or increase access to transit.

The agencies also created and enforced strict urban design standards and development bidding rules.Developers wishing to build in the Transbay District had to align their plans with these requirements, which included controls over the form and use of the buildings, the size of city blocks and the type of activation and street scape at the ground level.

At the time, the belief was, “Nobody’s going want to do that! The developers are going to want flexibility,” recalled Jose Campos, manager of planning and design review at the successor agency to the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, the Office of Community Investment and Infrastructure. Rather than being repelled, developers and architects appreciated the clear framework and flocked to the area.

Such design requirements support transit and contribute to a successful multimodal hub. They create the opportunity for people to live and work in vibrant neighborhoods and help shape a future where walking, biking and taking transit not only feel pleasant and safe but actually become the best options for moving around.

The Importance of Aligning Leadership

In European countries, it’s often the national government that leads the delivery of the vision for station and station area development projects. Although that’s not true of projects in the United States, some universal rules of government collaboration apply worldwide and are particularly important to recognize here in our highly fragmented community of transit providers.

Recruit local champions and regional support.

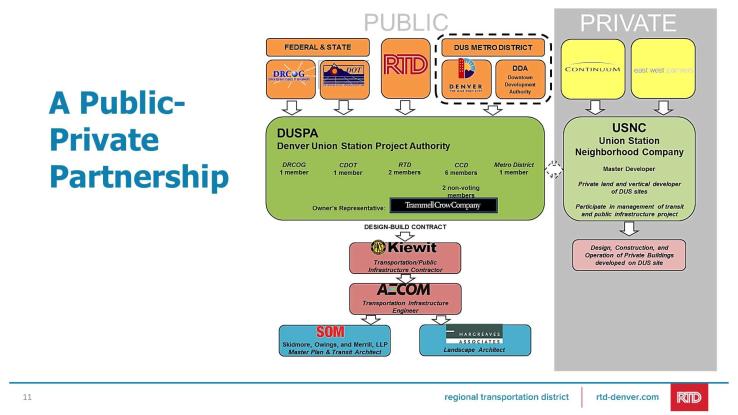

Once a wasteland of vacant lots and under-used parking, the area around Denver Union Station has become the central node of the region’s rapid transit plan and of Denver city development. Bill Sirois, Senior Manager of Transit-Oriented Communities at Denver’s Regional Transportation District (RTD), presented a coordinated vision for the station, which was developed and implemented thanks to local championship and a multi-year collaboration among public and private partners.

In 2001, RTD purchased the 19.5-acre property that included the station. With its partners — the City and County of Denver, the Colorado Department of Transportation and the Denver Regional Council of Governments — RTD jointly funded and developed a station masterplan, establishing a shared and integrated vision of new transit and a development program for the station. In November 2004, Denver Metro voters approved Fastracks, a regional sales tax measure allocating $5.5 billion for a regional transportation plan and funding 10 percent of the station redevelopment plan. In addition to this local funding, the station project received 60 percent of its funding from federal loans that were secured thanks to the City and County of Denver, which backed the loans. This allowed the Denver Union Station Project Authority to move forward with construction of the station.

Pair funding streams with guidance and state oversight.

Through gas taxes, vehicle fees and other funding streams, California provides critical funding to expand and improve transit, to make cities comfortable for walking and biking and to repair roads. This year, SPUR joined California State Senator Jim Beall and more than 100 organizations and cities in the campaign to reject Proposition 6, which aimed to repeal the gas tax. If it had passed, the Bay Area alone would have lost $3.6 billion over the next 10 years.

Funding is not the only thing that the state can provide. Local governments don’t always have the tools and capacity to realize statewide goals. For example, a goal to focus office development in the immediate surroundings of a station can hit a barrier when there’s strong local pressure to build housing or public opposition to maximizing density.

Meea Kang, director of the Council of Infill Builders, and Kate White, state deputy secretary of environmental policy and housing coordination with the California State Transportation Agency, presented a station district financing concept they have been exploring. They propose forming a state-level oversight committee and respective local boards to coordinate every taxing entity in a high-speed rail station area.

Local governments could then access a tax-increment fund to align their station area plans with statewide requirements that include investing in the public realm and infrastructure, developing commercial buildings and affordable housing in the station district and more. In addition to allowing for new funding schemes, the state could provide planning tools and expert advice to local governments as appropriate. If applied to San Jose, this concept could help support the construction of the new Diridon Station and the infrastructure needed to create a people-centered urban realm around the station.

Involve the private sector as a “critical friend.”

From the early stages of the project in 2006, the Denver Union Station Project Authority benefitted from its partnership with a private master developer, the Union Station Neighborhood company. While the authority managed the delivery of the multimodal hub and the station area public spaces, the master developer brought ideas for how to fund the ambitious vision for the project, which led to an amendment of the station masterplan. The master developer was also responsible for building out the parcels around the station, coordinating with the infrastructure work and providing placemaking guidance. The revenues from land sales contributed to public realm upgrades and rehabilitating the historic station building. Without this public-private partnership, Denver Union Station might not have fulfilled its ambitious vision and goals.

In Great Britain, the national government is investing in its largest-ever infrastructure project, the extension of its high-speed rail network to the northern part of the country, known as High-Speed Rail 2 (HS2). When the British Parliament approved the first phase of the extension in 2013, it required the creation of an independent advisory committee, the HS2 Independent Design Panel, whose role is to offer critique and review of key design processes. The panel acts as a “critical friend,” according to Professor Sadie Morgan, director at dRRM Architects, who chairs this group of 45 people from the private sector. She explained how the panel helps the national government integrate design excellence in every step of the project (procurement, engineering, landscape, architecture, arts curation and more), showing that it can foster community support — and doesn’t have to be more expensive.

Conclusion

The visioning process that the Diridon partner agencies have undertaken is setting the stage for Diridon Station’s legacy. It will determine whose lives will be transformed, in what ways and to what extent. By putting the user first in the visioning and decision-making process, the transformation of Diridon Station has the potential to pioneer seamless transit integration, become a great urban place, attract economic growth and foster inclusive, sustainable development both around the station and in greater San Jose. As we learned at the symposium, the community, the state and the private sector can all be partners, supporters and collaborators along the way.

Thank you to our guest speakers for sharing their expertise. You can watch videos of their presentations or access their slideshows below:

On the role of stations:

Daniel Jongtien, Partner / Architect at Benthem Crouwel

Video

Slideshow

Etienne Riot, Director of Research and Innovation at AREP designlab

Video

Slideshow

On land use and great design around stations:

Bill Sirois, Senior Manager of Transit-Oriented Communities for RTD Denver

Video

Slideshow

Georgia Sheridan, Senior Manager of Transit Oriented Communities at LA Metro

Video

Slideshow

Jose Campos, Manager of Planning and Design Review at SF Office of Community Investment and Infrastructure

Video

Slideshow

On state, regional and local collaboration:

Professor Sadie Morgan, Director at dRMM Architects

Video

Slideshow

Kate White, Deputy Secretary, Environmental Policy and Housing Coordination, CalSTA, and Meea Kang, Senior Vice President at Related California

Video

Slideshow

California State Senator Jim Beall, Representing the 15th Senate District

Video