With more than $10 billion in rail investments and 240 acres of developable land, San Jose’s Diridon Station is the largest transportation and city-building opportunity in the Bay Area. Bringing together Caltrain, BART, statewide high-speed rail, light rail, and local and regional bus services, Diridon represents a chance to integrate more transit modes more seamlessly than any other place in the region. It also provides an opportunity to create an anchor of public life in greater downtown San Jose and expand the urban core of the South Bay. Because it will be on the first high-speed rail line in the United States, the project has both statewide and national significance.

But success at Diridon is not assured. As one of the first cities in the country to build a high-speed rail station served by lots of other modes of travel, San Jose doesn’t have the benefit of daily experience to understand what makes these kinds of stations, and the places around them, succeed. Simply put, we have a lot to learn.

As part of that learning process, SPUR and the Knight Foundation took a delegation of South Bay elected officials and transit agency leaders to visit high-speed rail stations and cities in the Netherlands and France this past summer.

While there are numerous high-speed rail systems in the world worth visiting (including China, Germany, Japan, South Korea and Spain), we selected the Netherlands and France because their rail planning, station design and city building around stations offer lessons that are particularly applicable in San Jose.

In the last 15 years, the Netherlands has redeveloped six of its stations into major multi-modal hubs, adding high-speed rail and dramatically shortening travel times to the rest of Europe. We visited three of them: Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Utrecht. These three cities (along with the Hague) are part of the Dutch Randstad, a megalopolis with a population about the size of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Out of 400 rail stations, the Netherlands chose six key projects to turn into world-class high-speed rail stations, catalyzing urban development and economic growth. Image courtesy Jan Benthem, Benthem Crouwel Associates.

Out of 400 rail stations, the Netherlands chose six key projects to turn into world-class high-speed rail stations, catalyzing urban development and economic growth. Image courtesy Jan Benthem, Benthem Crouwel Associates.The redevelopment of Amsterdam Centraal is an example of a retrofit of a historic station. The project included adding a subway line and rail capacity, improving bicycle access and improving the traveler’s experience — all within a highly urbanized and constrained environment.

The redevelopment of Rotterdam Centraal is recognized as one of the best examples of a modern high-speed rail station. Heavily bombed during World War II, the city had been rebuilt around the automobile. The redesigned station, opened in 2014, puts pedestrians first with functional and intuitive design and high-quality public spaces. An especially important precedent for San Jose, it’s a success story of how to adapt an auto-oriented place to walking, biking and transit.

Rotterdam Centraal spills into public spaces that are reserved for pedestrians and bicyclists. Photo by Laura Tolkoff.

Rotterdam Centraal spills into public spaces that are reserved for pedestrians and bicyclists. Photo by Laura Tolkoff.Utrecht is the smallest city in the Randstad but the most important transportation node in the country. The redesign of its central station added six tracks and simplified rail operations to allow for more reliable and more frequent service. The project created a new urban center that bridges the historic 13th-century urban fabric on one side of the station with the modern city on the other side.

In France we visited Lille, where high-speed rail service was introduced in 1994. France pioneered the European high-speed rail network, opening the first high-speed rail line on the continent between Paris and Lyon in 1981. A few decades ago, Lille was at the center of France’s rust belt and on the decline. With the addition of high-speed rail, it became a gateway to London, Paris, Amsterdam and Brussels, which reinvigorated the city’s economy and put it on the map culturally and economically.

Lille, France, used the arrival of high-speed rail as an opportunity to rebuild downtown and reshape the city’s economy. Photo by Eric Eidlin.

Lille, France, used the arrival of high-speed rail as an opportunity to rebuild downtown and reshape the city’s economy. Photo by Eric Eidlin.After reflecting on our visit, we came away with nine key takeaways. Each provides important lessons for San Jose as it aims to build a world-class transportation hub:

1. Successful projects start with an ambitious, unconstrained vision.

Every city we visited began with a bold vision of what could be. They did not start by working within existing fiscal constraints or presuming that the way things are is the way they will always be. A bold concept has the benefit of bringing all partners to the table, working together toward an ambitious vision. It helps to attain commitments and sustain them through political and economic cycles.

Lesson for Diridon: As an existing station offering many transit services, Diridon has the potential to get weighed down by constraints. Transit providers and other stakeholders should strive to look beyond their immediate concerns and work together to develop an expansive and comprehensive long-term vision.

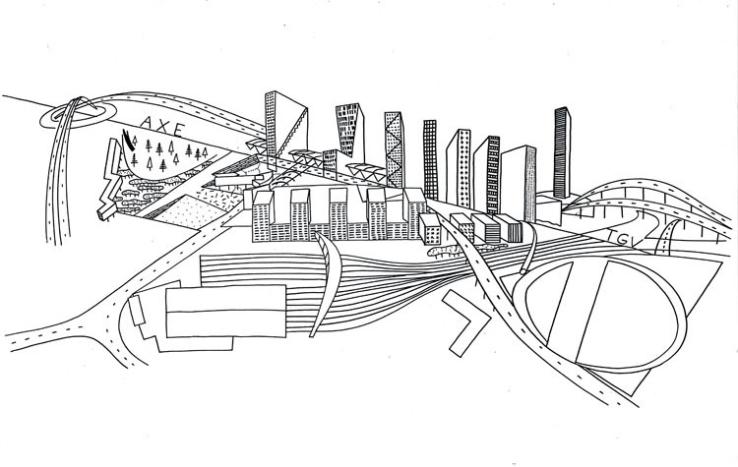

The plan for Lille started as a sketch by world-renown Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. Today, most French stations still spring from an unconstrained, imaginative sketch. Image courtesy of Andreas Heym, AREP.

The plan for Lille started as a sketch by world-renown Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. Today, most French stations still spring from an unconstrained, imaginative sketch. Image courtesy of Andreas Heym, AREP.2. Rail infrastructure must be designed first.

Decisions about rail infrastructure, such as the train alignment, the number of tracks and the location of platforms, should take place before other decisions, such as the location of nearby development. As Andreas Heym, the director of international development for AREP, the architecture and planning arm of the French Railways, told us: “Rail infrastructure needs to be designed perfectly. It is the only thing you will not change for 100 years.”

In the Bay Area, we often develop land around a station first and then try to squeeze in the transit. The French and Dutch models work the other way around, beginning with the railway operations and track infrastructure, then designing “from the platform out.”

Lesson for Diridon: The railway tracks and operations at Diridon should be aligned and coordinated as best as possible before laying down any new steel or concrete. Diridon has long-been operated as a terminal, meaning many trains are stored or serviced there. Taking the European approach would reserve the rail infrastructure at this important hub for maintaining high-quality service, not for storing trains.

Remaking Utrecht Centraal started with redesigning the tracks and platforms, simplifying the system to maximize reliability and on-time performance. Photo by Ratna Amin.

Remaking Utrecht Centraal started with redesigning the tracks and platforms, simplifying the system to maximize reliability and on-time performance. Photo by Ratna Amin.3. Great stations focus on maximizing a great traveler experience.

For transit to be successful, it needs to compete well with the car on time, safety, cost and comfort. This is especially true as we attempt to lure people from their cars. This requires taking a people-first approach to planning the station and its services. Transit service must be fast, frequent and reliable, and the station should have a lot of amenities — not just food and drink but things like charging stations and travel information services.

In both France and the Netherlands, passenger-serving retail has become a major source of revenue to help subsidize rail operations. With business totaling more than half a billion euros annually in the Netherlands, ProRail — which manages Dutch stations and station development— has developed a comprehensive benchmarking and planning approach to maximize the traveler’s experience of each station to support both ridership and non-rail service revenue generation.

The new wing of Amsterdam Centraal includes a light-filled atrium and new restaurants for both ticketed passengers and customers who are not traveling anywhere. Photo by Ratna Amin.

The new wing of Amsterdam Centraal includes a light-filled atrium and new restaurants for both ticketed passengers and customers who are not traveling anywhere. Photo by Ratna Amin.Lesson for Diridon: Make decisions based on the traveler’s experience, and ensure that everything within the station area is well-designed and connected. Planners should ask: How easy is it to transfer from a train to a bus, or to travel through the station with luggage? How long is the walk, and is it direct and intuitive or do you have to go out of your way? Is it difficult to orient yourself when you get out of the station? What kinds of services and amenities will best serve people’s needs?

Utrecht Centraal handles the highest number of passengers per day, and many of them use it as a transfer point. It’s designed with lots of natural light and good sightlines to help travelers orient themselves. Photo by Laura Tolkoff.

Utrecht Centraal handles the highest number of passengers per day, and many of them use it as a transfer point. It’s designed with lots of natural light and good sightlines to help travelers orient themselves. Photo by Laura Tolkoff.4. Transportation projects are also city building projects and should be planned in tandem with urban improvements.

Adding a new rail line or redeveloping a rail station is a catalyst for growth, yet we often plan transportation projects in isolation. The French and Dutch models integrate transportation with urban development. They pay special attention to its place-defining effects, being careful to integrate the station into the city, rather than allowing it to overwhelm or separate neighborhoods.

Several projects are under development adjacent to the newly remodeled Utrecht Central. A new pedestrian bridge over the tracks will connect them. Photo by Laura Tolkoff.

Several projects are under development adjacent to the newly remodeled Utrecht Central. A new pedestrian bridge over the tracks will connect them. Photo by Laura Tolkoff.Unlike highways or airports, rail stations can be knit into dense urban centers. Trains are a relatively quiet and space-efficient way to move large numbers of passengers. Train stations promote growth around them — and that growth symbiotically generates ridership.

Lesson for Diridon: The is one lesson that San Jose is already applying as it coordinates with BART, VTA, Caltrain, high-speed rail and future development partners. It will be important to remember, however, that city building is a years-long process, not a one-time event. As development moves forward over time, the city should review plans as they change and coordinate city modification with transportation improvements and new building development.

5. New high-speed rail service and a well-planned station can help reshape a city’s economic identity and brand.

Great urban stations boost economic activity and create jobs. Not only are stations and services revenue generators, but the ability to link to other urban areas promotes a new level of economic opportunity for the whole city. In Lille, for every euro invested in the station, four euros were generated outside of the station.

Ten years after opening its station, Lille won the prestigious European Capital of Culture designation. Today, Lille is in the running to be the new home to the European Medicine Agency (a major employer with 900 staff members) since its post-Brexit decision to relocate from London. These economic opportunities would not have been possible had Lille not connected to the rest of Europe via high-speed rail.

Lesson for Diridon: New rail service at Diridon has great potential to reshape the city’s economic position and reputation as a great place to live, visit or do business. It is also an opportunity for San Jose to share its brand as a vibrant, historic and diverse community located in the seat of innovation.

6. Stations, and the streets and areas around them, are first and foremost public spaces.

“The station is just a public space with a roof on it,” said Jan Benthem, co-founder of Benthem Crouwel Architects and the principal architect for Rotterdam, Amsterdam and Utrecht Centraal stations. They are central gathering places teeming with activity and people, whether or not they are boarding a train.

Stations should function and feel like public spaces. Photo by Jan Benthem, Benthem Crouwel Architects.

Stations should function and feel like public spaces. Photo by Jan Benthem, Benthem Crouwel Architects.Lesson for Diridon: The public must come first in how Diridon Station, and the surrounding area, is designed. A station provides building blocks for public life: places for people to share a meal with their coworkers, for peaceful demonstrations, for cultural presentations and for children to play.

7. The station and station area must prioritize passengers who arrive by foot, bike and transit.

In every city, we saw an emphasis on creating inviting spaces around the station and focusing on forms of mobility that take up less room, such as walking and biking. Cars require a lot of space (especially for parking), move relatively few people and diminish the experience of a place for people using other travel modes. Rotterdam and Utrecht, in particular, had to reverse several decades of auto-oriented growth. What they found, as Sebastian de Wilde of ProRail put it, was that “if you make the station and its surroundings car-limited, and even car-free, then you have a place where people will stay.”

Nowhere was this clearer than in Utrecht, where the city was busy returning a roadway into a canal and public park for pedestrians and bicyclists to enjoy. In the 1960s, the city had drained the canal and turned it into a road to give cars direct access to the historic center. Today, the city is reclaiming its center as a place for people.

Lesson for Diridon: Emphasizing parking structures and auto-oriented access will diminish the quality of the place. With a focus on bike storage at the station and dedicated bike infrastructure leading to and from it, Diridon could also help the city achieve high levels of bike ridership.

8. Local leadership, coupled with the right state and regional planning tools, are key to success.

Remaking stations and station areas is a long process, so it’s critical to have committed and vocal political support at the local level. In 1980s Lille, then-mayor Pierre Mauroy wanted high-speed rail to come to his city and — despite the skepticism of France’s president — created a new public entity, SPL Euralille, to develop a master plan for the station and a project delivery structure to implement it. Importantly, the nearby cities and region were also part of this public entity; they helped ensure that the station and high-speed rail not only benefited Lille but also the region. Without these efforts, high-speed rail would not have come to Lille, and the city would have continued to decline.

But local leadership alone is not enough. In every city we visited, the national government was key to success, playing a role in providing policy frameworks, political support, technical support and/or financial resources. In the Netherlands, the state selected six “key projects” (stations of national significance) and then encouraged the individual cities to produce their own master plans for the stations. The national government reviewed the plans to make sure they were sufficiently ambitious and feasible, and then committed 1 billion euros to help implement them.

Lesson for Diridon: Local support, vision and leadership can make or break a project. There is no guarantee that high-speed rail will come to San Jose. Some observers would prefer to see the route travel over the Altamont Pass rather than the Pacheco Pass, which would mean bypassing San Jose altogether. Therefore, continuing to be vocal and strategic about the desire to bring high-speed rail to San Jose is essential.

9. Compromise and collaboration are not optional.

Every city we visited had complicated flow charts listing the many public and private partners responsible for station and station area development. In each case, all of the responsible parties put aside their own primary interests and committed to achieving a bigger vision. They recognized that this would achieve more than if each agency moved forward independently. The benefit of working collaboratively cannot be overstated. As Andreas Heym of AREP said, “Everyone will get less than they wanted but more than they expected.”

Lesson for Diridon: All key stakeholders — the City of San Jose, the California High-Speed Rail Authority, VTA, BART, private developers and other public agencies — must work together to form a cohesive and formal partnership. The end result will be greater than the sum of Diridon’s many parts.