The downtown districts of San Francisco, San José, and Oakland all face high office vacancies and shuttered storefronts as hybrid workplaces and declining tourism lower the daytime population that supports commercial activity. Office vacancies are at historic highs for all three downtowns, estimated at 27% in Oakland and 30% in San José and San Francisco, according to commercial real estate firm Colliers. But even before the onset of the pandemic, Bay Area downtowns faced significant challenges, including traffic congestion, patchy transit service, and insufficient housing and shelters. Many residents, nonprofits, small businesses, and artists found themselves priced out.

As cities grapple with an oversupply of commercial spaces, leaders have an opportunity to revitalize downtowns in a way that creates more housing opportunities for low- and moderate-income workers, enhances economic mobility through small-business ownership, invests in public infrastructure, and nurtures community arts and culture organizations.

What is the role of public policy in downtown revitalization? Couldn’t we just allow market forces to dictate how our cities evolve? That is certainly an option, but without policy intervention, SPUR estimates that it will take decades for older office buildings to become fully leased. In the meantime, downtowns will continue to struggle to attract visitors and shoppers, small businesses will continue to close, and housing affordability will remain challenging. If downtowns are left to flounder, municipal budgets will shrink, and the quality of public services will deteriorate — not just in the neighborhoods immediately surrounding the downtowns, but citywide. San Francisco, San José, and Oakland don’t have to wait for the market to dictate how and when change happens. Cities can actively pursue strategies to creatively repurpose obsolete spaces into new uses, whether it be affordable housing, arts spaces, or educational hubs.

The public sector plays a crucial role in downtown economic development, primarily by providing regulatory relief and offering economic incentives for revitalization projects. But that’s not enough in today’s climate, given dwindling public resources at the local level combined with slow and bureaucratic decision-making processes. The scale of transformation needed to revitalize downtowns will require a new governance model that encourages public-private partnerships. Public or quasi-public authorities empowered with land use powers, streamlined decision-making processes, and financial resources could invest in community priorities such as affordable housing, infrastructure, parks, the public realm, and affordable spaces for small businesses, community organizations, and the arts.

We don’t have to look far to see how this governance model would work. Until 2012, San José, San Francisco, and Oakland all had state-authorized redevelopment agencies dedicated to reinvesting in areas that were declared “blighted.” State law gave these agencies the power to acquire properties, sometimes through eminent domain; capture revenues generated from new development projects through a mechanism known as tax-increment financing; borrow against future revenues to pay for infrastructure; and subsidize both private development and affordable housing. In their later years, these agencies were effective in working with communities to provide needed housing, jobs, and other infrastructure on a large scale, but their roots in the 1945 Community Redevelopment Act point to a troubled history. Bringing back this type of model will require both close examination of the achievements of redevelopment agencies and reckoning with the harms imposed by urban renewal.

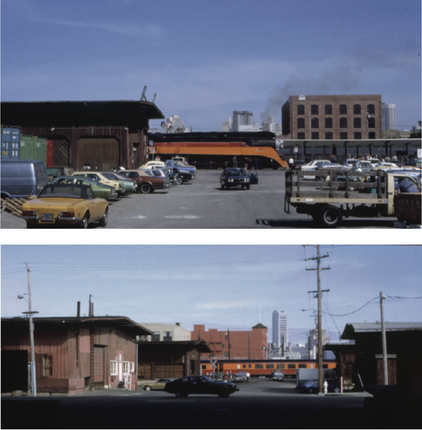

One recent redevelopment success is San Francisco’s Mission Bay area. The former industrial railyard — built on bay fill and once dominated by obsolete industrial uses — has been converted to a mixed-use district. Approved in 1998, the Mission Bay plan was implemented through a public-private partnership of property owner Catellus (the real estate arm of the Santa Fe-Southern Pacific railroads), the City of San Francisco, and the University of California San Francisco (UCSF). Mission Bay North — the area between Townsend Street and the Mission Creek Channel, from Third Street to Seventh Street — was designated as a primarily residential area connected to the San Francisco Caltrain station. Mission Bay South — bounded by Mission Creek Channel to the north, Mariposa Street to the south, Interstate 280 to the west, and the bay to the east — contains housing, commercial offices, research and development labs, the UCSF medical campus, the Chase Center arena, hotels, and retail stores. Mission Bay South was developed concurrently with the Third Street rail project, which connects southeastern San Francisco neighborhoods to downtown San Francisco and Chinatown. According to San Francisco’s Office of Community Investment, almost 2,000 homes, or 28% of Mission Bay’s 6,500 housing units, are affordable to lower-income families. Additionally, the project areas encompass more than 40 acres of public parks and open spaces.

Mission Bay’s transformation is a result of concerted efforts by both the public and private sectors. Importantly, it was the redevelopment agency that threaded the needle between private investors’ imperatives and community objectives. City and community leaders rejected Catellus’ initial plan, but eventually, the San Francisco Planning Department produced a plan that became the area’s guiding document. The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency then shepherded the project over multiple mayoral, planning director, and property ownership transitions. The agency had the authority to negotiate the terms of the plan to ensure that it was feasible for the developer but also delivered on important community benefits like public infrastructure and affordable housing. It also brokered a deal with UCSF to bring in a new hospital and research center, which attracted private biotech companies to San Francisco. The agency sold bonds to pay for the up-front costs of streets, parks, and infrastructure. Moreover, it created a dedicated revenue source to subsidize housing, nearly doubling the share of affordable units required by law.

Today it’s well understood that the legacy of redevelopment is tainted by discriminatory practices that targeted and harmed low- income communities of color. San Francisco’s redevelopment agency cleared 60 blocks in the African-American neighborhoods of the Fillmore/Western Addition in the 1950s, displacing thousands of households, small businesses, and cultural institutions. Around the same time, San José’s redevelopment agency demolished homes in the areas adjacent to downtown, displacing stable immigrant neighborhoods. In Oakland, urban renewal projects in the 1950s and ’60s — including freeway and BART construction, a new federal postal facility, and port expansion — pushed many Black and working-class families out of West Oakland.

As cities plan for the future of downtowns, it’s worth reviewing lessons from previous eras when, like today, local governments faced the need to transform struggling industrial and commercial areas into thriving mixed-use places. Specific governance and financing models made it possible for cities to enter into public-private partnerships to create new neighborhoods and sustain revitalization through various economic and political cycles. The question now is how to update those models to reshape cities in a way that promotes inclusive economic growth and prioritizes affordability and racial and socioeconomic diversity. San Francisco, San José, and Oakland don’t have to wait on the market to deliver change. Nor are they doomed to repeat the harms of the past. Creating new authorities with land use powers, efficient decision-making processes, and sufficient financial resources can help urban planners and policymakers as they work with the public to map the route to more prosperous and equitable downtowns. ✹