The Bay Area has been completely outdone. The Puget Sound region just raised $27 billion at the ballot box for transit expansion. Compare that to two of our local measures in 2016: BART’s bond (Measure RR) raised $3.5 billion for maintenance and $200 million for future expansion, and VTA’s sales tax (Measure B) will raise $6 billion, with about $2 billion for transit expansion.

Sound Transit 3 (ST3) is an astounding rail transit expansion, with new rail lines stretching across the region. The three-county Central Puget Sound Regional Transit Authority (Sound Transit), established in 1993, is charged with building and managing a rail system for an area of more than 1,000 square miles, serving 2.9 million people in 50 cities. Sound Transit also runs the Sounder commuter rail, Sound Transit Express bus service and the Link light rail system, giving it greater transit reach than any one Bay Area agency. That $27 billion from Puget Sound residents covers half the funding for the $54 billion ST3 package: 62 new miles of Link light rail, 37 new stations, two new bus rapid transit lines, an extension of Sounder commuter rail and an array of other bus transit projects by 2041.

A package as big as ST3 was a long-time coming. Perhaps the most pivotal moments for ST3 actually happened in 1968 and 1970, when voters in Seattle and the surrounding King County twice turned down raising $400 million to build out a 49-mile BART-like rail system and 500 miles of bus routes. The bonds would have leveraged $900 million in federal funding, money that ultimately went to Atlanta to build MARTA. Consequently, the Seattle region fell far behind the Bay Area in transit; BART opened as a 28-mile system in 1972, and Muni Metro began service in 1982.

Following that rail failure, Puget Sound voters did invest in a robust bus system (King County Metro). However, it was not until 1996’s Sound Move that voters supported building rail, and the region’s first miles of light rail finally opened in 2009. The subsequent $17.8 billion Sound Transit 2 won in 2008, after a failed attempt, in 2006, at passing a combined roads and transit measure. The 2016 campaign for ST3 echoed the original vision of the 1960’s: “Sound Transit Proposition 1 [ST3] will connect the entire region with mass transit, from trains to buses”.

ST3 passed with just 54 percent of the voters across the Sound Transit District saying yes —only a simple majority is required in the State of Washington. California requires two-thirds voter approval, forcing much more compromise about what gets funded, and where the revenue comes from. ST3 included three tax increases: a property tax, sales tax and car-tab tax (what we call vehicle license fee in California). The other $27 billion to pay for ST3 is expected to come from federal grants, bond proceeds, fares and surpluses.

What the Bay Area Can Learn from Seattle

ST3 offered a big regional transit vision to voters and put together different funding sources to make it happen. Plan Bay Area does part of this — it lays out a regional program of investment and a set of funding sources to pay for it all. But what Plan Bay Area doesn’t do is offer a cohesive vision for growing the region’s transit system; it’s transit vision is only a collection of many local transit priorities.

While the scale of Sound Transit’s vision and triumph are enviable, actually building ST3 faces familiar challenges. State legislators in Olympia are holding hearings on how to roll back some of the less-popular funding sources (the car tab tax) and reform the agency’s governance (one proposal suggests replacing the appointed board with an elected board, like BART’s). Supporters are disappointed with how long it’s going to take to build: Some growing urban communities such as the Ballard neighborhood won’t see their new light rail connection until 2035. Light rail extensions to Everett, Issaquah and Tacoma are scheduled for 2036, 2039 and 2041, respectively. Building the ST3 network also requires a complicated subway tunnel through downtown Seattle, acquiring new land and building new rail bridges.

Like all U.S transit agencies, Sound Transit doesn’t own enough land or have the land use authority to make sure that development at transit stations produces riders to fill all the new train service (this is perhaps an area where Seattle can learn from Bay Area successes, and failures). When it comes to affordable housing development near transit, ST3 is innovative: It includes $20 million for affordable housing loans and a requirement that 80 percent of Sound Transit’s surplus land (land no longer needed after construction) be offered for affordable housing development, where 80 percent of the homes should be affordable, to households earning 80 percent of the area’s median income.

Sound Transit, like its peers, is accused of ignoring outlying and lower-income communities. In the Bay Area, the term “geographic equity” is often used to describe a political process of making sure that each community gets something from a transportation revenue ballot measure. While geographic equity seems reasonable, it can also lead to projects mismatched with where the greatest needs are. Sound Transit’s “sub-area equity” policy formalizes this concept, requiring that revenue be used to benefit the sub-area where it was generated (there are five sub-areas).

Despite the challenges, there is no doubt that the City of Seattle and the Puget Sound region have an enviable enthusiasm for transit. Two years ago, the City of Seattle voted for a $930 million “Levy to Move Seattle”, which includes funds to expand King County Metro’s “RapidRide” bus service within the city, delivering on the city’s promise of providing 72 percent of homes with transit that arrives every 10 minutes all-day, within a 10-minute walk from home. The year before that, Seattle voters approved $45 million per year, for six years, to buy more bus service from King County Metro. The City’s transit commitment is working: From 2010 to 2016, 45,000 jobs were added downtown and only 5 percent of them have been drive-alone.

So how have Seattle, Tacoma, Bellevue and other cities in the region managed growth for so long without a rail system? The answer is buses. Sound Transit and King County Metro’s buses have been the workhorses of the region, carrying about 88 percent of all transit trips. Now that the Bay Area is considering using more regional buses on highways, we could learn from Sound Transit’s use of stations in the middle of highways (“in-line stations”) and express bus lanes into, and through, downtown Seattle (even using a 2-mile subway tunnel). Passenger ferries, operated by the Washington State Department of Transit, are also a key part of the Puget Sound transit system.

Today, the Link light rail is gaining in popularity: Trains serving two new stations through Capitol Hill and University of Washington were packed right away when the light rail opened in 2016. Last year, Sound Transit’s ridership jumped 23 percent over the previous year, serving 142,000 passengers on an average weekday. ST3’s goal is to carry about 800,000 daily trips on light rail in 2040 (Muni carries about 720,000 daily; BART about 430,000). The popularity of light rail in Seattle should inspire dense parts of the Bay Area without local rail lines, including much of Oakland and mid-Peninsula cities. The Link light rail system operates almost entirely in its own right-of-way; trains seldom stop outside of stations.

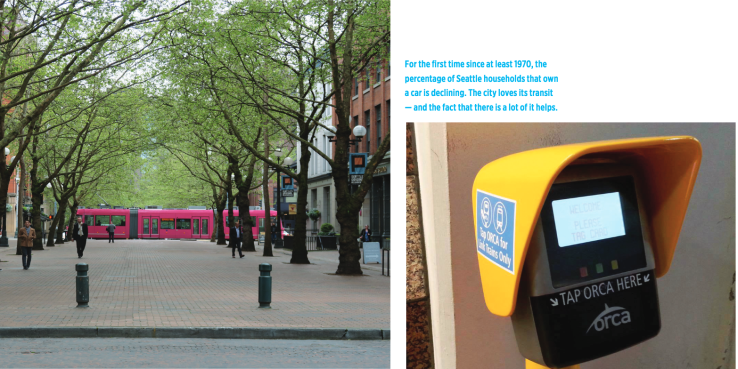

The Bay Area can also learn from ORCA, the Puget Sound region’s version of Clipper, which is also operated by Sound Transit. ORCA users have access to daily and monthly regional passes that work across operators: Passes like these could be a game changer for the usability of Bay Area transit. The ORCA LIFT card program, which offers fare discounts for people with little or no income, is among the most innovative transit affordability programs in the U.S because of its simplicity and reach. The objective is to get monthly passes into as many hands as possible, to attract people to use transit. With far fewer transit agencies, the Seattle region is undoubtedly a less complex place to do multi-agency passes, but ORCA shows us that regional passes are not only feasable, they advance the goals of transit. Employees are winners from regional passes: 65 percent of transit boardings in King County use an employer-subsidized fare card, which is the reason jobs have boomed with so few new cars.

While Seattle’s rail system is newer and smaller, both regions share the same transit choices: Will we build communities around rail stations, and solve the first/last mile problem? Will we make trains that are frequent enough, and reliable enough, to compete with driving? Will our transit agencies be financially sustainable, and able to pay for today’s needs and tomorrow’s? After all, great transit isn’t just lines on maps.