Daniel Burnham’s plan for San Francisco provides a revealing glimpse at how much greener our city would have been had we followed his vision, as well as an understanding as to how much more important the role of parks in creating a great city was viewed at that time. In his chapter on parks and playgrounds, Burnham states, “The important part which adequate park spaces may be made to play in civic life is now generally recognized and need not be dwelt on here.” Somehow, in the century that has since passed, we regrettably have forgotten the important role that parks play in our civic life. How else can we explain the acceptance of the bits and leftover pieces that are passing for new open space in developments such as the Transbay redevelopment area, or the fact that major new parks are not being developed in concert with the massive addition of residential units that is occurring South of Market?

Burnham’s plan proposes that parks, and the parkways linking them, create the “breathing space” that is essential for a great city. Supporting one proposal to develop a parkway, Burnham extolled, “Probably no other expenditure of money will bring surer returns in health, happiness and consequent good citizenship than the sum requested to construct this parkway.” As someone who has spent several decades promoting our city’s green spaces as an essential element of our environment, I find Burnham’s understanding of cost and benefit to be truly visionary. Given the need to redress the current inequities of an open space program that has left many neighborhoods without sufficient access to parks or green streets, a review of Daniel Burnham’s plan left me yearning for what might have been if we had followed through on his vision.

Imagine the Sunset District with a large, centrally located public square, with parkways radiating from it to connect with other green spaces such as Twin Peaks, the Panhandle and Lake Merced. Imagine the Panhandle extended from its current location all the way to Market Street where a grand "Place” forms the focal point for a network of parkways and "market ways" ¾ a greenway network that is economically as well as visually critical to civic vitality. Burnham believed that connecting landscaped boulevards to parks and playgrounds throughout all the neighborhoods would enhance the value of civic life for all of the city's residents.

An underlying principle of Burnham’s city vision, reflecting San Francisco’s unique geography, was the preservation of hilltops for public access and open space. Burnham thought that each hilltop park should include a playground supporting a variety of recreational activities. These would be arranged in terraces from which a good view of the city might be found. The achievement of his general objective was realized at locations such as Bernal Heights and Twin Peaks.

Burnham's vision continues to influence city planners and spurred the preservation of hilltops for open space. A few of Burnham’s parkway plans, such as Park Presidio Boulevard, also materialized. McLaren Park, which Burnham hoped would become the “Universal Mound Park,” remains a large green space anchoring the southern portion of the city, although not the active recreation playground that would engage the surrounding neighbors.

Some take issue with Burnham for his grand and monumental (i.e., “old world”) planning ideas, for he applied them across the board regardless of the land use. Industrial areas were to subscribe to the same principles as residential and commercial zones. The portion of the City South of Market Street (SOMA), formerly industrial but now quickly transforming to residential, would especially have benefited from Burnham’s vision and the implementation of a network of “Places” throughout this area.

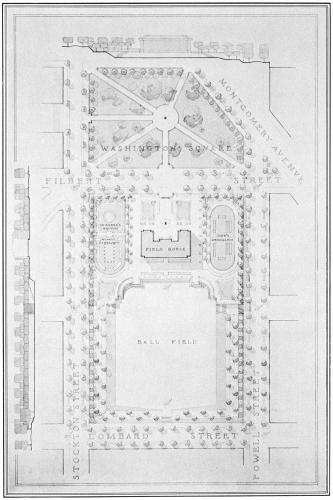

Burnham's design for Washington Square.

Burnham’s vision was realized more fully in Chicago. Burnham quotes Henry Foreman of Chicago extensively when detailing the nature of the parks to be developed in San Francisco. "(Parks) must be more than breathing spaces with grass, flowers, trees and perhaps a pond and a fountain. They must afford gymnasia, libraries, baths, refectories, clubrooms, and halls for meetings and theatricals. They must be useful day and evening, summer and winter. The public must receive a continuous and ample return for its investment ¾ daily dividends in health, happiness and progress.” (Emphasis added.) Unfortunately, San Francisco's parks have rarely fulfilled Foreman’s mandate.

Imagine the impact on the quality of life, and public content with our neighborhoods, as well as our civic and political dialogue, if we had created the type of meeting spaces Burnham and Foreman thought were necessary parts of a city's fabric. As Foreman put it, “The large feature (of the park) is an assembly hall shared by men, women and children as a shelter, and arranged for lectures and entertainments. The ceiling is high, showing open timbers. A stage is provided, and in close communication, a refectory (i.e., dining hall). … Flanking this hall are the wings accommodating the social and athletic functions for men and women respectively.” This is a marvelous description of the Lake Merced Boathouse as originally constructed. It is demoralizing to recognize the depths to which that facility has now fallen through neglect and mismanagement.

As I think about the many meetings my neighbors and I have attended in the low-ceiling basement of the Park Branch Library in the Haight, I envy Chicago, where their Park District followed the “assembly hall” vision Foreman proposed. Even with the renovation of the Harvey Milk Recreation Center, scheduled for next year, lack of funding is preventing the realization of just such a hall for theatrics and social functions. Despite what the community would prefer, we will be reproducing the same already overcrowded footprint of the center due to insufficient capital funds.

Perhaps more important than inadequate funding is our continued lack of vision as to how parks should be developed and the services they should provide. In Burnham’s day, city planners knew that parks were essential to a city’s well being. Today, San Francisco's General Plan lets developers building new neighborhoods, with thousands of new residents, claim balconies and rooftop gardens as “open space.” While balconies may be fine, they are not a substitute for expansive parks where our children can play. The City is thinking project by project rather than evaluating the regional impact of all projects taken together. Only in large redevelopment areas such as Mission Bay do we gain larger parks and meet an acreage required by the city, although even there some of the sites for active recreation are still marginal (i.e. under the freeway).

Our open-space and park planning, both for new neighborhoods and for older neighborhoods lacking adequate recreational facilities, urgently needs an overhaul. It’s not too late for San Francisco to implement Burnham’s best ideas and to create an even better example of “city beautiful” in the 21st century.