Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing consistency. Remember that our sons and grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty.

–Daniel H. Burnham

Make no mistake about it: The civic leaders who commissioned Daniel Burnham in 1904 to create a forward-looking vision for San Francisco wanted a “big plan.” So did Burnham himself. And the plan he delivered in 1905 didn’t disappoint. Even unrealized, it is grandly beautiful as a plan ⎯with lovely drawings and maps, spare and stately prose, and painstaking documentary photographs to demonstrate its foundations in careful research and objectivity. This plan was no pie in the sky, but the positive results of a thorough reconnaissance of the terrain and contemplative study of the city layout from an aerie (designed by Willis Polk) perched high atop Twin Peaks. Small wonder that it was reprinted in a facsimile edition at the very time when San Francisco was issuing a new and very different but no less beautiful and influential plan ⎯the Urban Design Plan for the Comprehensive Plan of San Francisco, published in 1971 when Allan B. Jacobs was director of the Planning Department.[i]

The bigness of the Burnham plan spoke to San Francisco’s growing sense of its own significance on the national and world stage, at least in the minds of its civic leadership ⎯politicians such as former San Francisco Mayor James D. Phelan, businessmen including financier Rudolph Spreckels and the press, led by San Francisco Chronicle publisher Michael deYoung. For these men, San Francisco was not merely in need of “improvement” and “adornment,” although these were the guiding principles of the association founded by Phelan that would go on to commission Burnham’s work. More than that, San Francisco had clearly reached a critical mass that made a master plan itself central to the scale of its collectively imagined destiny as a great city, one that could no longer place its faith in higgledy-piggledy speculative development, surges of booms and bust, and spotty philanthropic gifts of public ornament. A city of such stature demanded to be pro-actively envisioned and carefully stewarded so that it might favorably compare to the great cities of the past, for visions of these cities fired the sense of civic responsibility among the leaders of society. To the minds of Phelan and his well-heeled, well-connected colleagues, a suitably inspiring “imperial San Francisco” called for the architectural vocabulary of ancient Greece, Rome and Constantinople, tempered by the urban design strategies of 19th century Haussmannized Paris and re-“imagineered” according to the proto-Disneyesque cosmopolitan pastiches typical of World’s Fair architectural grandeur in fashion at the turn of the century.[ii] Not for nothing did one of Phelan’s biographers rhapsodize, “Pericles could not have loved Athens more than this man loved San Francisco.”

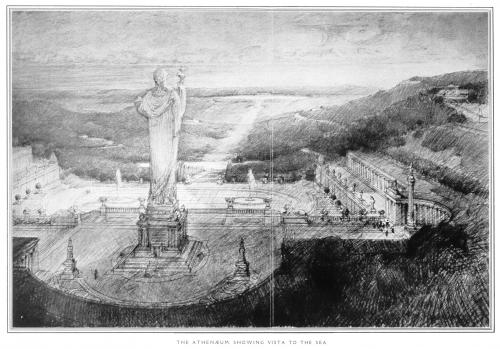

In this sense, the scale that it was hoped San Francisco would attain under the Burnham Plan seems at first glance to be expressed mostly through its architectural punctuation marks ⎯ the proposed monuments at Telegraph Hill, the Ferry Plaza, Civic Center and Twin Peaks, where Burnham sketched in an Athenaeum for Phelan’s very own “Athens,” complete with a colossal allegorical embodiment of San Francisco [fig. 1]. But the problem, as these proposals also immediately demonstrate, is that imagining the “monumental” as a concrete manifestation of San Francisco’s particular ambition to be a great city was challenging then – and remains a challenge for a city that continues to debate what, at heart its scale ought to be.

Fig. 1: Burnham's monumental design for Twin Peaks.

I want to begin from the premise that seeking to understand the scale of San Francisco’s greatness and developing a vocabulary capable of expressing it was one of the central issues posed by the Burnham Plan, for better or worse. Achieving such understanding remains essential to getting San Francisco’s urban design features right ⎯in both its major monuments and landmarks, and in its minor, everyday details. And further, I want to insist on the obvious: Scale is not necessarily equivalent to physical size. Indeed, there are certain things about the topographically imposed scale relationships of San Francisco (water and horizon to land, hills to flats and valleys, etc.) that make it particularly difficult to get size right.

For a sense of this dichotomy, fast forward from Burnham’s Athenaeum to Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s Cupid’s Span, installed in 2002 as part of the effort to capitalize on another earthquake-induced opportunity for a clean slate –this time for a San Francisco waterfront minus the blight of the Embarcadero Freeway [fig. 2]. Somewhat related in their mythic, allegorical vocabulary, the two works are similarly compromised by the vastness of their respective sites. What we suspect from trying to imagine the never-built colossus of San Francisco (especially in comparison to the looming presence of the radio tower we ended up with atop Twin Peaks) is confirmed by the weak visual anchor provided by the frankly gigantic Cupid’s Span, which ends by looking merely toy-like when visually juxtaposed with the nearby Bay Bridge. So at first glance, the Burnham plan can be faulted for seeming to equate civic greatness with a rote, monumental super-sizing, for defaulting to “imperial” scale ⎯in spite of what our eyes and the rest of our bodies might tell us empirically when we view comparable monuments as part of the cityscape or stand next to them on a street corner or plaza. When it comes to certain key locations in San Francisco, big might never have been quite big enough.

Fig. 2: "Cupid's Span."

But Burnham also grasped this, I think. In fact, I suspect the monuments were proposed largely to placate his patrons ⎯they have a kind of half-baked, flown-in-from-elsewhere feel to them. So look again, not at the statuary, amphitheaters and other architectural flourishes he provided, but at the plan itself as a map of potential connections, concentrations of density and suggestive possibilities for urban encounters. Read the various sections on the “General Theory of the City,” the “Perimeter of Distribution,” the “Civic Center,” “Mission Boulevard,” “Public Squares and Round Points.” Seen in this light, the plan proposes a kind of nascent “pattern language” specially tailored for San Francisco, and despite its taste for flat-topping hills and terracing what was left of them, a number of provocative ideas remain. Imagine the possibilities of the transit system that might have been enabled by Burnham’s network of cross-town boulevards and the bike paths that might have eventually replaced the bridle paths on proposed major parkways. Fantasize about pushing your stroller or being pulled by your dog from Civic Center all the way to the ocean on an extended Panhandle connecting downtown to Golden Gate Park. Think of working in the commercial districts that might have grown up around the major round points, dispersing business energy throughout the city, rather than concentrating it in a still pretty soul-less downtown. Burnham’s plan continues to capture our imagination, even given the things we don’t like about it, precisely because it is a big plan, one that embraces the whole city at once in its big vision.

This is where everything becomes more interesting. How does the bigness of the plan prompt us to explore the generosity of spirit we know to be the true measure of San Francisco’s greatness? How might the fine grain of San Francisco indicated by the dense grid that persists in the interstices between Burnham’s boulevards represent complexity ⎯that is, be a part of this scale of greatness ⎯without necessarily translating to smallness or staying the same?

For starters, take our Civic Center, which didn’t turn out quite as Burnham imagined it, but went down a similar path of equating greatness with an oversized, “imperial” public space. The expanse of the plaza dwarfs most attempts to animate it and has frustrated more than one urban designer on a mission to fix it. Yet one of the most interesting recent interventions came as part of a public art initiative sponsored by San Francisco State University and the Arts Commission in 2005. Many of the projects were conceptual in nature and their visual presence was relatively subtle. This was certainly the case with Wang Po Shu’s Musicity, a bell tuned the same pitch at which the dome of City Hall would resonate in an earthquake and installed in the plaza directly across the street from the mayor’s balcony. [fig. 3] For the course of a month, schoolchildren, tourists, passersby, bike messengers, the homeless, government workers and political hacks all took their turns ringing the bell, delighting in the ability to fill the plaza with their individual sonic presence. The noise reportedly drove the mayor crazy ⎯until he rang the bell himself. Po Shu’s bell itself was pretty small, but it raised a big question: would “fixing” Civic Center entail installing something equivalently big to anchor it, or do we need to better understand how to program its largeness to allow the diversity of San Franciscans ⎯the true source of the city’s fine grain ⎯to find resonance at its seat of power?

Fig. 3: Wang Po Shu's "Musicity", installed outside City Hall.

Or look at Burnham’s sketch for what he calls “Mission Boulevard.” [fig. 4] Organized as a central roadway framed by smaller, neighborhood-serving traffic lanes and striped with planted spaces that also contain walking and bridle paths, it looks a lot like the new Octavia Boulevard that is one of the best things to happen to the city in years. Both draw inspiration from a Paris that may still be “imperial” but has continued to work well for a lot of people. When the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Black Rock Arts Foundation commissioned artist David Best to build a temporary “temple project” on the green space at the end of the boulevard, everyone knew that the location was nothing like the vast expanse of the desert “playa” where Burning Man erects its annual city-away-from-the-city, with a work by Best as its centerpiece. Instead, Hayes Green is just big enough to make a friendly urban public place. Best’s design was perfectly sized to its site, with a human scale that rendered it welcoming and airy ⎯not at all overbearing, but a landmark “monument” nonetheless. [fig. 5] In this case, however, the monumentality of the “temple” drew its energy from the ambition of the boulevard itself, whose confident sweep was grand enough to align the structure’s filigreed, peaked roof with the torqued tower of St. Mary’s seen in the distance, creating the small visual miracle of a temple made of plywood scraps holding its own with a cathedral made of stone.

Fig. 5: Temple project on Octavia Boulevard.

In this sense, the urban design of a city’s infrastructure ⎯its street grid, its connectivity, its functionality ⎯is no less a part of its civic expression of greatness than the monuments, trophy buildings and other forms of public art that might adorn it. All of them should work together to demonstrate a commitment to creating a city that celebrates and serves its people well. And this is where I disagree with the Chronicle’s John King, whose recent retrospective look at the Burnham plan concluded complacently that “a great city…is judged by quality of life, not quality of design ⎯and by that standard, San Francisco fared just fine.”[iii]

Has it really? Try telling that to the nanny who has to get from her home in the Richmond to her work in Noe Valley every day, or the young man who looks down the long light-rail line from the Bayview to downtown and wonders why there’s no job for him there, or the family that reluctantly moves from the city to find affordable housing. Being glad to have escaped a quasi-Continental sprinkling of statuary and peristyles that would most likely have saddled us with more obsolete Victorian frippery on the order of the regrettable Pioneer Monument does not exempt us from the task of continuing to imagine what civic greatness might look like. It does not absolve us from continually challenging ourselves to come up with an evolving, contemporary urban design vocabulary capable of expressing core civic values. And these values really should be “big,” meant to speak to the best of us and to the city as a whole, no matter the actual size or form in which they manifest themselves.

Back to Burnham’s time. Among others, turn-of-the-century architect A.C. David was impatient with San Francisco’s inflated view of itself. “Its citizens like to talk about it as the Paris of America,” he wrote. “But French restaurants, electric lights, and a prevailing atmosphere of gaiety do not make a Paris. A metropolitan city must be tied together by a plan which provides for every essential economic and aesthetic need; and San Francisco still remains devoid of such a plan.”[iv] In 2006, David’s words still ring true, with no immediate prospects for redress on the horizon. We live in a era that may have given up on the monumental stylings of ancient Rome, but defaults instead to cautious neighborhood plans, ever more finely delineated in area and largely micro-managed by self-nominated groups of stakeholders who sometimes seem no less caught up in the trappings of power than San Francisco’s 19th century “imperialists.”

So 100 years later, the lesson of the Burnham Plan might be this: Make big plans and risk confusing master planning with mastery ⎯visually and politically, as a practical matter of everyday life. But make only little plans, and risk that without a greater, more generous and holistic vision to organize them, they are not really plans at all ⎯just merely marginal gestures that all too often disguise wishes that things would stay mostly the same.

[i] Daniel H. Burnham, Report on a Plan for San Francisco (San Francisco: Sunset Press, 1905), reprinted by Urban Books (Berkeley, 1971). Allan B. Jacobs, et. al., The Urban Design Plan for the Comprehensive Plan of San Francisco (San Francisco: Department of City Planning, 1971). We still have a lot to learn by reading both of these documents together, and they are both in need of a new reprinting.

[ii] The best book on this vision of San Francisco remains Gray Brechin, Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

[iii] John King, “The Great quake: 1906-2006. Grand S.F. Plans That Never Came to Be (April 12, 2006), p. A-1.

[iv] Quoted in Gray A. Brechin, “San Francisco: The City Beautiful,” Visionary San Francisco, Paolo Polledri, ed., (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1990), p. 52.