Today, the air in City Hall, in the neighborhoods, and among developers is thick with talk of area plans. From Treasure Island to the Shipyard, with stops at Rincon Hill, Mid-Market, Balboa Park, Showplace Square, Octavia and Market, Visitacion Valley, and the whole eastern edge of the City along Third Street, planners and communities are taking a fresh look at the City’s physical development. For planners, lawyers, environmental reviewers, and traffic counters, these are busy times.1

But it’s easy to lose sight of the power and scope of plans that transform neighborhoods, especially when those plans become steel and jobs, kitchens and labs, sewer lines and parks. Wrapped in the details, we can be surprised when we finally do look around, to see a city transformed. In this issue, which profiles the rapidly changing neighborhood of Mission Bay, guest editor David Prowler brings together articles that look at the Mission Bay Plan and how the area’s urban design, environmental sustainability, history, and emergence as a potential medical-research nucleus make it integral to the future of the city.

Mission Bay today is a very different place from six years ago. Six years ago you could have taken the freeway to the trailer park and the sprawling half-empty Port Maintenance Facility, except that the freeway overhead was stubbed out at Third Street. The bridges linking the empty lots to the north to the empty lots to the south were seismic hazards.

Today, in the summer of 2005, it is a very different picture. The N Mission Bay streetcar is standing-room only on its way to SBC Park, the 42,000-seat ballpark that has been described as one of the greatest ballparks in baseball. Thousands of people live in the high-rise and mid-rise towers fanning out across from the ballpark. They shop at the local Safeway and the Borders Books and next spring will be checking books out of their branch library. Kids play at the Mission childcare center. In the near distance, south of the retrofitted Lefty O’Doul Bridge, rises the new UCSF campus in Mission Bay South, with three laboratory buildings occupied and a striking community center under construction. The headquarters for California’s stem cell research effort is moving to the neighborhood.

Underlying this growth is the enormous investment in infrastructure—sewers, streets, sidewalks, utilities—that made it possible. In just six years, Mission Bay has been the site of a radical transformation unequalled in San Francisco since the City laid out the Avenues flanking Golden Gate Park.

Background

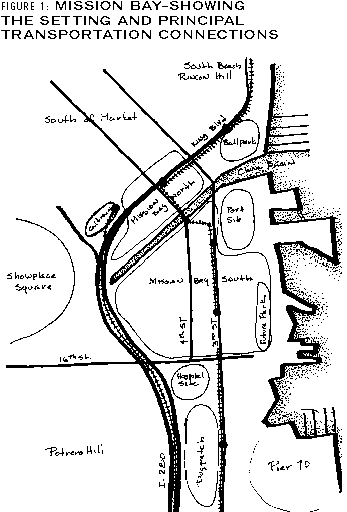

Mission Bay is the over-300 acres bounded by I-280, the Bay, the Caltrain tracks and station to the north, and Mariposa Street. It was an actual bay—and when Mission Dolores was dedicated in the late 1700s, you could have canoed between them. Little by little, it was filled in to become wharves and railroad yards.

What we see on the ground today was a long time coming: after World War II, the flight of jobs and housing to the suburbs, the movement of industry to cheaper locations, the replacement of train traffic by truck and air, left San Francisco and virtually every other North American city, with underutilized railyards. Our new neighborhood now known as Mission Bay, consisted of some 300 acres between the elevated I-280 freeway and the bay—flat, built on fill of unknown quality, toxic, and surrounded by disused piers and other neighborhoods with industries dead or dying.

The Santa Fe Pacific Realty, an offshoot of the railroad, was formed to develop such parcels. So in 1981 they presented the city with a mundane proposal of mid-rise buildings. They were told to come back with a real design. They came back with a spectacular plan of high-rise buildings set on lagoons, in recognition that the site was once a bay. Again, with its image so different and seemingly unconnected in plan or economic pattern to the city, it had a short life. At some point the neighbors did their own plan of Sunset-like blocks and single-family houses. Then in 1984, a new team of development professionals was brought in. With the Planning Department as client and paid for by the developer, yet another plan was produced. This plan was later refined by the developer, and through a series of negotiations with the City, a development agreement was signed in 1991. It won design awards. But nothing happened.

The planning of Mission Bay was handled by four mayors, three planning directors, and successive corporate incarnations and leadership on the ownership side.2 It has been defeated at the ballot. Plans have featured high-rise office buildings, a Home Depot, canals, a domed stadium, a Metreon clone, and a rented wetlands with a full-time staff. And finally it’s happening.

The Mission Bay Plan

The Mission Bay Plan calls for 6,000 new homes, 28 percent of them affordable with subsidies generated by the project; over 50 acres of parks; 6 million square feet of flexibly zoned commercial space; and a 43-acre UCSF campus. Figure 2 shows the overall land use plan and building sites currently completed or under construction.

Adoption of the Mission Bay Plan in 1998 was the beginning of a projected 30-year buildout, with the rate of development to be determined by market demand. Parks and other public improvements (such as transit links, police and fire station, and a public school) are to be triggered by the rate of development. Progress has been extraordinary. The neighborhood north of the channel and the new campus are well underway, with more growth planned for the next few years. This fall, site preparation will begin on the first non-campus housing development south of Mission Creek.

Housing and Retail

The Plan allows about 6,000 housing units, in a mix of building types. Half will be built north of Mission Creek and half south. Twenty eight percent of these will be affordable—almost double the amount required by redevelopment law. These units will be indistinguishable from the neighboring market-rate units and distributed throughout the project area. Private developers include 255 of these in their market rate projects and the remaining 1,445 are to be built by nonprofit organizations on land provided to them by Catellus. Mission Bay may turn out to be the San Francisco neighborhood with the most socioeconomic integration, with wealthier and lower-income homeowners and tenants living side-by-side.

Already, 1,079 housing units in the area have been built and are occupied. Of these, 148 are affordable. Another 551 residences are in construction, and yet another 1,150 units will begin construction within a year. Amy Neches, senior project manager at the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, predicts that “if the market stays strong, we’ll see 3,500 to 4,000 units in Mission Bay in the next five years.” Along with the housing already built, there is 110,500 square feet of neighborhood-serving retail and over half a million square feet of office space (which includes the new home of the State’s Stem Cell Initiative). Another 100,000 square feet of retail is currently under construction.

UCSF Campus

Catellus Development Corporation and the City jointly donated 43 acres to the University of California, enabling UCSF to double its size and grow its research capability. Construction on campus has been rapid with Genentech Hall, the Arthur and Toni Rock Hall, the California Institute for Quantitative Biomedical Research (QB3) and the 3.2-acre Koret Quad already built and occupied. This fall, the Mission Bay Community Center, an International Orange–colored four-story building by Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta, will open. Student housing (430 units) and parking garages are under construction. At build-out, the campus will contain 20 buildings, employing over 9,000 scientists and technicians (all are shown in Figure 2).

Commercial Uses: Biotech, Office, Manufacturing

The campus is ringed on three sides by six million square feet zoned for a broad, flexible range of uses—from lab to office, multimedia, or manufacturing. The zoning for this area is very broad, enabling almost any kind of non-residential use, with offices able to cut ahead of the line for office-space allocation under 1986’s Proposition M, the City’s ceiling on office growth. But office-space demand has been slow in Mission Bay, as elsewhere. The Gap leased a new 280,000 square foot building in Mission Bay in 2000 but was unable to sublease the never-occupied building. Soon they will be moving in their Old Navy operations.

Of the six million feet of available space, 2.1 million has been bought by Alexandria Development, a nationwide builder of “science hotels,” incubators for labs and biotech researchers.

Parks

Nearly 60 acres of parks are included in the plan, in a variety of sizes and configurations—a Marina Green–type park at the Bay, Mission Bay Commons; a Panhandle-like strip; a children’s playground; sports courts; Koret Quad; and several mini-parks. Generally, the parks will be developed by the master private developer (Catellus or successors), as parcels adjacent to them are developed. So as a housing block is built, for example, a park across the street gets built. Already the southern edge of Mission Creek, accessible from Channel Street, has been developed into a landscaped “linear” park. Maintenance of the parks will be paid for by a Mello Roos tax3 on Mission Bay property owners.

Additional Plan Elements

A 500-room hotel, a public school, and a combined police and fire station are in the plan as well. At this time, there is just beginning to be interest in a Mission Bay hotel, but as Mission Bay is built out, the location near the University, the ballpark, and potentially a set of specialty hospitals should create a demand. The building of a school and police and fire station are triggered when Mission Bay’s population reaches certain thresholds.

Infrastructure

Much of the cost in dollars and labor in developing Mission Bay has been spent building the underlying infrastructure—the streets, sewers, utility conduits, curbs, storm drains, water-treatment facilities, telecommunications systems, and, on the UCSF campus, a cogeneration power plant for the campus. Before any of this could be built, though, the City had to map out the streets and create official parcels—a function the Department of Public Works rarely has to do and that took longer than anyone expected. All this effort—creating the armature for development—is common in areas where sprawl is the norm, where farmland is becoming sliced into subdivisions. But established cities like San Francisco are rarely called upon to design and put in place these necessary elements, and gearing up to do so here took a long time. The City is still struggling with the challenges of approving the maps and improvements.

Ownership of the land is divided between the City and Catellus. The pattern was sorted out through a set of land swaps that were not completed until almost nine months after the plan was approved. The plan calls for a new set of streets, to be built by Catellus according to the City’s specifications. Catellus is to pay for these streets, along with a new utility system, sewers, and other improvements with reimbursement provided by the Redevelopment Agency’s access to increased tax revenues from development. As properties are built and assessed, they provide new taxes, and this increment is used to pay for the infrastructure which made the development possible in the first place. As taxes increase, the increase is used to pay for the improvements. But if the new taxes are insufficient, it is the developers’ responsibility to make up the shortfall. The adopted plan estimated a cost of $200 million for the necessary improvements, including parks. That amount has already been spent and the Redevelopment Agency’s current estimate is double, at $400 million.

Construction Jobs

The City has established goals for the recruitment and hiring of San Francisco residents and firms, administered by the Redevelopment Agency. Overall, the goals are being met, with 30–40 percent of construction contracts going to local minority or women owned businesses. Twenty-five to thirty-five percent of jobs have gone to residents referred from programs run by Young Community Developers and the Mission Hiring Hall. And these are good jobs—about 2,000 union construction jobs. Other Mission Bay employers are pitching in also. Half of the 150 jobs at the Mission Bay Safeway were filled through City-funded jobs programs.

The adopted plan differs from previous plans for Mission Bay in some very significant ways. The previous 1991 plan was rigid, a set of linkages and formulas and triggers that gave Catellus certainty but removed flexibility. Nelson Rising, CEO of Catellus, explained why he decided to terminate the old plan. “The previous plan called for office use north of the Channel and housing south of the Channel. It required that for every 700 square feet of office one housing unit be built—artificially linking two markets usually not in synch. To require a developer to take that risk makes no sense. And the housing could only be built as nonprofits built their affordable units, but there was no financing mechanism for public infrastructure or affordable housing. The plan required way too much ground floor retail, much more than could be supported. And the plan couldn’t accommodate UCSF. And finally, the plan required a $30 million deposit before we could do environmental investigation. It was a non-starter.”

Plan Elements

The new plan relies on financing tools of the Redevelopment Agency. Under California law, redevelopment agencies can sell bonds based upon projected increases in property tax revenues and capture those increased taxes to repay the bonds. This is a handy tool—the currently anticipated cost of the streets, parks, sewers, and other infrastructure in Mission Bay is more than $400 million. In the 1991 plan, these costs were borne solely by Catellus. Now they are covered to some extent by taxes generated by the new development. Above that, the cost is borne by property owners who have imposed upon themselves an additional Mello-Roos Tax.

In redevelopment districts, housing is always subsidized from the tax increment, so there is a guaranteed source of funds for affordable housing in Mission Bay. For the non-profit built housing, the subsidy cost is about $100,000 per unit.

The adopted plan is not dependent exclusively on the office market. Because the six million square feet of space is zoned so broadly for office, research and development, life science, or commercial use, as market demand shifts buildings can be developed to meet that demand. The empty Gap-leased office building east of Third Street shows how important this flexibility is. Markets change. And the owner’s construction schedule is determined by their perception of the market rather than a set schedule.

In an earlier SPUR article (“How to Turn a Parking Lot into Apartments, a Library, and a Grocery Store the Hard Way,” May 2004), I stressed the necessity for a public/private partnership to meet the twin tests of political and financial feasibility. Without the votes and popular support, projects won’t be approved. Without logic in the marketplace, they won’t get built, and neither the developer nor the City will get the benefits for which they negotiated.

The adopted plan calls for more than 2,000 fewer housing units than the 1991 plan but “the financing is available for the affordable housing to actually be built” according to Marcia Rosen, director of the Redevelopment Agency. In fact, the first housing built and occupied in Mission Bay was Rich Sorro Commons on Berry St., built by Mission Housing Development Corporation for low-income families.

The world surrounding Mission Bay, at least to the North, has changed enormously in the last few years. In a very real sense, the city grew to Mission Bay’s border, creating the critical mass necessary to jumpstart development north of the Channel. Previous Redevelopment efforts had created a new neighborhood in South Beach, with over 2,800 units springing up in 20 years. The Ballpark, too, helped establish the district as a place with a real identity. (While some neighbors were adamant during the entitlement of the Ballpark that it would destroy the neighborhood, Nelson Rising at Catellus foresaw it as a boon to residential development in the area. And he was right.) The Embarcadero, with palm trees, lighting, and Muni Metro, weaves Mission Bay North into the city. The Third Street Light Rail will connect all of Mission Bay to downtown as well as to the neighborhoods to the south, such as Bayview and Hunters Point. And the UCSF campus provides a central feature and identity for the area south of the channel.

Mission Bay As a Medical Hub

The City and Catellus joined in donating 43 acres south of the Channel to UCSF for the creation of a biomedical research campus. UCSF is among the nation’s pre-eminent biomedical research institutions and its ability to secure grants and conduct research was limited by its ability to house laboratories and other research space. The University was constrained in its ability to grow on Parnassus Heights, hemmed in by residential neighborhoods and bound by an agreement banning expansion. Mission Bay was one of three finalist sites under consideration by the Regents and it was this donation of the land that clinched it.

The City hoped to reach a number of goals by retaining UCSF. With 21,000 employees, the school is second only to the City government in numbers of workers in San Francisco, and the City wanted to retain those well-paying jobs and capture future job growth. After build-out, 9,000 scientists and technicians will work at the Mission Bay campus. UCSF has done a good job of linking up with City College and other employment training programs to ensure that San Franciscans get a good shot at these jobs. And the City and Catellus hoped that the new campus would be a magnet for private related users such as biotech companies. It has been the City’s hope that the campus would spawn a biotech cluster in much the same way that Stanford served as a catalyst for the growth of the computer industry. After all, biotech in the Bay Area employs 85,000 people at 800 companies, generating $4 billion a year in revenue. Catellus hoped to attract buyers and renters of new buildings; the City hoped to attract businesses to pay taxes and employ residents.

Biotech in San Francisco has gotten off to a slow start. South San Francisco has offered a critical mass of biotech companies, with 40 percent of Bay Area biotech jobs located there. “No one at UCSF in the last 40 years could start up a new company anywhere near Parnassus, so they learned to cope with distance and settled in South San Francisco or the East Bay” said UCSF Vice Chancellor Bruce Spaulding. According to Spaulding, companies will be attracted by the reality of a campus rather than the anticipation of a campus. It’s not “plan to build it and they will come”—it’s build it and they will come. As that happens, interest rises. Banking on that, Alexandria Real Estate Equities, which specializes in life science projects, will begin construction next year of a five-story lab/retail/office building, with space targeted toward start-ups. Over time, Alexandria plans 2.1 million square feet of lab space at Mission Bay. The entry of Alexandria into Mission Bay’s biotech arena is “beyond a vote of confidence; to me it’s a sign it will happen” said Amy Neches, Redevelopment Agency project manager. And the City’s successful effort to land the headquarters of the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (the “Stem Cell Headquarters”) should increase our prestige as a leader in biomedical research.

But there are hurdles. According to Spaulding, “the questions still before us are—will the advantages of proximity be overwhelmed by the cost premium of being in an urban area, and will pricing in the Mission Bay area be more competitive than it has been for the last five years?”

A New Hospital in Mission Bay?

Confronted with a State-mandated need to replace seismically vulnerable hospitals (AB 1953), both UCSF and San Francisco General Hospital are eyeing parcels within Mission Bay as potential sites for new facilities. UCSF is farther along in its effort. They plan to move in-patient care facilities to Mission Bay to address the needs of children, women, and cancer patients. This spring, the University of California Regents approved pursuing a long-term lease with Catellus for a 9.7-acre site just south of 16th Street to accommodate at least 210 beds. These acres would not suffice for the new hospital complex. UCSF would need to acquire a total of 14.5 acres. The hospital south of the campus should be built by 2012. UCSF is considering adding an additional 400-bed hospital on the Mission Bay campus by 2030.

While a hospital cluster at Mission Bay would offer operational cost savings over time and enable joint planning between UCSF and San Francisco General, it could present some challenges to the City’s ability to meet the goals of the Mission Bay Plan. While the campus donation was intended in large part to spawn a demand for off-campus biotech users, the potential hospitals would be tax-exempt and need space proximate to the campus that would otherwise house those users. Already, a prime biotech site at 654 Minnesota Street, just south of Mission Bay, has gone from private biotech lab use to a proposed use as UCSF offices. But UCSF’s Spaulding asserts that a hospital use increases the attractiveness of Mission Bay to biotech and medical-related companies. Those needing a clinical setting for testing—by offering experimental treatments or devices to patients—would benefit from the proximity to a working hospital. And he points to the broad use categories permitted in the Plan for the commercial space as evidence that the Plan never envisioned that all the commercial eggs would be in the same basket.

The Redevelopment Agency and the University have worked out a proposed arrangement designed to mitigate the loss of taxes earmarked for housing. Under the proposed agreement, the University would purchase a 1.6 acre site already set aside for affordable housing for $5 million and, without recourse to City subsidy, develop 160 affordable apartments—a contribution worth an additional $16 million. These would be targeted to lower-income UCSF employees. (UCSF has over 21,000 employees. Half live in San Francisco, so there should be plenty of potential tenants.)

UCSF has also agreed to fund a joint planning effort to assist San Francisco General in deciding on the possibility of co-location. On the one hand, San Francisco General is staffed by UCSF doctors, so co-location makes a lot of sense. But on the other hand, the City does own the current hospital site so no land would have to be acquired. And the current central location is a benefit to the population served by San Francisco General. Mayor Newsom recently appointed a task force to recommend a course of action for the replacement of San Francisco General, and they are expected to do so by end of summer.

Around Mission Bay

Mission Bay doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Just as SBC Park and growth in South Beach sparked the development of Mission Bay, Mission Bay sets the tone for its surroundings and will be affected by changes around it. To other than hardcore planning wonks, the division between Mission Bay and neighboring districts may become harder to discern.

South Beach

South Beach is a 20-year old redevelopment area, with a mix of incomes primarily consisting of high- and mid-rise housing developments. At the northern edge, Lend Lease Corporation is constructing the Watermark condominium project, and across the Embarcadero will be the new cruise terminal. Closer to SBC Park, on King Street, a 10-story, 132-room hotel is under consideration. At 123 Townsend, we’ll find Al Gore’s new media headquarters.

China Basin Building and China Basin Landing

The China Basin Buildings predate the modern Mission Bay—at one time it was a distribution center for food coming into the Bay Area. Now, as the world around it has changed, so has the nature of the China Basin Building and the neighboring China Basin Landing. They have a vacancy rate of just three percent, unheard of in the City’s lagging office market. A $100 million expansion of China Basin Landing is in the works.

Western SOMA

The Board of Supervisors has appointed a task force to make recommendations regarding the western edge of SOMA, generally bounded by Townsend Street and the Caltrain tracks, Bryant Street, 3rd and 7th Streets. It’s an area with some large developable sites, including the Flower Market and the San Francisco Tennis Club. As the City considers investing billions of dollars to bring rail closer to the density of downtown at the Transbay area, it is worthwhile to look at the potential to build over the train yard and tracks leading into the Caltrain Station at 4th and Townsend on the border of Mission Bay and SOMA. The tracks are on land now owned by Farallon Capital Management, zoned for office uses, and with a Caltrain easement for the trains.

Showplace Square

Showplace Square is in a wrinkle in the map of San Francisco: it’s not South of Market or the Mission or Potrero Hill. It borders on Mission Bay, but that border is a freeway. You might not have a reason to go there unless you are a designer to the “carriage trade.” That’s all going to change. The showrooms aren’t going away, but Bill Poland of Bay West Group has submitted to the City an ambitious plan to create a new neighborhood with housing and retail, cafes and parks. Currently in the environmental review process, his proposal would create 775 new housing units.

Under plans submitted to the City by Bay West, A.F. Evans Development, California College of the Arts, and Cherokee Investment Partners, other projects in what is being called the Design District could provide an additional 750 units, for a total of 1,500 (by comparison, the Rincon Hill Plan would create about 2,100 units). A.F. Evans will begin construction on 224 condominium units at 601 King Street at the end of summer 2005. Not far from Showplace Square, at 5th St. and Townsend, a new 50-room boutique hotel is planned.

Central Waterfront

Central Waterfront is the planners’ name for the area south of Mission Bay to Islais Creek, bounded by the Bay and I-280. Along with the rest of the “eastern neighborhoods,” this area has been a policy battleground for years as the City tries to balance the need for housing with the need for workplaces of various sorts other than offices. In December 2002, after two years of public meetings, the Planning Department released the proposed Central Waterfront Plan.

In most of the Central Waterfront Plan area, new housing and offices would be prohibited. (Some of that is land under Port jurisdiction, where the State Lands Commission bans housing in any event.) It includes a preferred alternative, which would allow housing along Third Street and preserve housing in Dogpatch. Dogpatch is the historic name for the neighborhood just south of Mission Bay, west of Third Street. It’s a funky mix of tiny Victorians, industrial space, new and converted loft buildings, Esprit Park, and the Hells Angels clubhouse. On Minnesota Street, the City’s only previously existing lab building is under contract to become a UCSF office building, and the former Esprit manufacturing and headquarters building is proposed for conversion to 142 residential units. Under the proposed Central Waterfront Plan, from 1,500 to 4,000 new housing units would be built along Third Street, with the future of the Potrero Power Plant as the key variable.

The City’s proposed plan is now three years old, and the draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) won’t be published until December 2005. An attempt to re-zone the area at the ballot, put before the voters in March 2004 as Proposition J, failed. And during the last decade, our industrial job base has shrunk for a variety of reasons beyond the control of zoning, reasons more related to the cost of labor here relative to Asia, truck and shipping access, and forces at work throughout the nation and the globe. It has been difficult for the Planning Department to get a handle on the future of the Central Waterfront because they are assuming the burden of crafting an economic vision for the City in a policy vacuum, and with only the tool of zoning at their disposal.

Citywide and south of Mission Bay, we have yet to craft such a vision. Housing? Industry? Labs? A mix? What kind of jobs do we want to see there and how do we prepare our residents to fill those jobs? What sectors provide the best jobs for our existing workforce and how do we attract or retain them? Does it help to offer payroll tax incentives or use other fiscal tools? How do we deal with the toxics legacy of the area? What is the relationship between the types of jobs to be spawned at Mission Bay and the Redevelopment plan for the former Hunters Point Shipyard? The City should launch an effort to get agreement on these questions and use that as an economic roadmap rather than leaving the Planning Department to grapple with how to zone our economic future. Voters recently passed a mandate for the City to develop an Economic Development Plan for San Francisco and work on that effort is slated to begin in the fall.

OTHER AREAS

Pier 70: The Port worked with international planning and landscape architecture firm EDAW, headquartered in San Francisco, this summer on a graduate student planning charrette to take another look at uses for Pier 70. This site just south of Mission Bay offers some complex development challenges. At one end is an operating power plant, a drydock is working on ships, use of most of the site is constrained by State Trust issues, there are several toxics issues, and many of the structures are both historic and structurally deficient. Yet this recent charrette offers an exciting vision that is expected to spur new interest in the area.

Port property south of the ballpark: It looks like part of Mission Bay, but this temporary parking lot for the ballpark, owned by the Port, isn’t in the Mission Bay plan. The Giants have another five years to go on their 10-year lease. Just across McCovey Cove from SBC Park, Piers 48 and 50 are designated for maritime use. The Port Maintenance Facility, relocated to make room for the ballpark, is there along with buildings under short term leases to maritime users. As Mission Bay builds out, this acreage, currently zoned for “public” use, will become an increasingly attractive development site. No plans are in place or under consideration for re-use of the site. The Giants have expressed interest in building a parking structure and, perhaps, an arena, but no proposal has been seriously floated.

What Can We Learn From Mission Bay?

Most plans underway elsewhere in the city are intended to skillfully weave new development into existing neighborhoods, which creates challenges as well as opportunities for those developments that are not found in Mission Bay. In part because of pre-existing conditions (the freeway and train tracks that border Mission Bay and the development challenges of landfill) and in part because of the extraordinary concentration of ownership by Catellus, Mission Bay was destined to express a character unique from the rest of the built City. In the Bayview, in the Better Neighborhoods areas (Market & Octavia, Central Waterfront, and Balboa Park), and in the eastern neighborhoods, in mid-Market, and in other areas in the planning process, the challenge is different: how to fit into existing communities while meeting contemporary needs for housing and community. The process is better informed by current residents and owners and the transition from past to future can be seamless and dispersed. But without a big stakeholder with an interest in investing in the neighborhood’s future, the day-to-day momentum can be severely diluted.

You can’t create by zoning, only allow or prohibit. The 1991 plan, abandoned by Catellus in 1996 allowed a lot of things: millions of square feet of office, tons of neighborhood-serving retail, and it mandated both in what order they must be built and at what rate. Offices, market-rate housing, parks, and affordable housing were all chained together. Right now it is easy to forget that not long ago the office market was roaring and that neither rental nor for-sale housing penciled out. The market has its own logic and unless the City is willing to step up to finance desired uses, all we can do is prohibit uses we don’t want. When we allow what nobody wants to build, we don’t get much to show for it.

Mission Bay evolved in response to the Ballpark and UCSF. Without such drivers, inertia can set in. At Mission Bay, the City was able to take advantage of twin opportunities: the expansion of UCSF and the Ballpark. We were forced to respond to UCSF’s decision-making schedule and to the Giants’ ballpark ballot victory. Both the Giants and UCSF presented the City with their schedules and the City was able to marshal the resources to meet them. At the same time, the imposed deadlines gave structure to the community and political reviews. Without them, planners and other officials can lose track of the goals of plan adoption and implementation. We have a number of planning efforts underway that are in their second decades, with no end in sight.

Mission Bay is the product of a special time, when economics and political will lined up. Former Mayor Willie Brown hitched the wagon of his administration to Mission Bay and the Ballpark. And he had the tools to make them happen: loyal commissions and a Board of Supervisors comprised of a majority of his appointees. But the Mission Bay Plan enjoyed popular support outside of City Hall as well. Housing advocates, clean water advocates, transit and bicycle constituencies, park advocates, labor unions, all lined up to support the plan. Foes of previous plans were effusive in their support. And to ensure that the plan would be negotiated and approved, Brown tapped long-time City Hall staffer, former Chief Administrative Officer, and widely respected civil servant Rudy Nothenberg to take charge. Along with Jesse Smith from the City Attorney’s Office and David Madway from the Redevelopment Agency, Nothenberg made it happen and set the tone for City departments to put priority on Mission Bay.

You can’t design a community; it has to evolve. It’s hard to build and design a new project of the size of Mission Bay with the quirky, surprising mix people love about cities. Maybe it can’t be done. Other than a historic firehouse, we won’t be seeing in Mission Bay the juxtapositions of architectural styles we see elsewhere or, really, the lapping up against a gritty neighborhood we see where South Beach meets the fringe of downtown or where the Western Addition redevelopment meets the Fillmore. Mission Bay isn’t an accretion of buildings over time; it is fulfilling a blueprint. Inevitably, something is missing. John Elberling, a nonprofit-housing developer in South of Market, is a longtime critic of Mission Bay planning and now a Mission Bay resident. He says, “Given twenty or thirty years, sure the district will evolve into something like a traditional neighborhood. You’ve got to give it time.”

One reason that the impressive growth of Mission Bay is so surprising on first encounter is that for most people, there’s no real reason to go there. Why would you? The parks are only partially built, the retail in place is not intended to be a destination, and there’s not yet a critical mass of residents in Mission Bay to support anything but the chain stores found there now. But the Redevelopment Agency’s Neches assures that the grain and mix of retail on 4th Street, south of the Channel, will be the pedestrian draw that Mission Bay so far lacks.

Is Mission Bay a “success”?4 What is success? Have we created another charming San Francisco neighborhood, with shops and a history? No. Was the process a model of community-based planning? No. Was the Plan showered with planning awards? No.

But the City had clearly defined goals in Mission Bay: to create a mix of housing types and affordability (with subsidies provided by Mission Bay development), to keep UCSF growth in San Francisco, and to set the framework for a new system of parks and other amenities. In redevelopment terms, it is en route to being a great success: a blighted area of toxic landfill and patchwork uses is now housing people and jobs. The assessed value of Mission Bay has increased 340 percent. The Redevelopment Agency will achieve a higher percentage of affordable housing, at all levels, than has been reached anywhere else in the City. University of California growth has been kept in the city.

It is useful to think about the limits of redevelopment, and the organic growth of cities over time. Redevelopment is not intended to be used as a tool where that growth is occurring—it is for districts where growth is stymied, with the Agency required under State law to prove that the area is blighted beyond the ability of the private sector to get it back on its feet.

It is early to call the question on how Mission Bay hangs together. Most of it has not yet been built; the park system isn’t in place; there isn’t anyone living in Mission Bay South and a critical mass of residents north of the Channel isn’t in place. Off the UCSF campus, there are only 5 residential buildings, the Gladstone Institute, and the empty Gap building. And the areas around Mission Bay, from Western SOMA to Showplace Square and south to the Central Waterfront, are poised to change in relation to Mission Bay.

The current Mission Bay Plan—the one being built—isn’t perfect. No plan, no building or neighborhood, no change in the city we once knew, is. But the proof is on the ground: people come home and cook dinner there, they shop for books and groceries, and they study and work in laboratories. Like true San Franciscans they gripe about Muni service and parking. And over time, Mission Bay won’t be a new neighborhood; it will be another neighborhood.

Endnotes:

1 Plans underway include Rincon Hill, Mid-Market Special Use District and Redevelopment Plan, Eastern Neighborhoods Interim Controls, (Summer 2005); Bayview Hunter’s Point Redevelopment Plan (September 2005); Market and Octavia (January 2006); Balboa Park, Glen Park, Mission Neighborhood Plan, Showplace Square/Lower Potrero Hill Neighborhood Area Plan, Central Waterfront Plan (June 2006).

2 When the Redevelopment Plans were approved in 1998, Catellus Development Corporation, the Santa Fe Railroad spinoff, owned nearly all the property in Mission Bay. Since then, much of the property has been sold to housing developers and to Alexandria Real Estate Equities for biotech development. In 2003, Catellus sold the remaining parcels to a subsidiary of Farallon Capital Management, a hedge fund that will sell them over time for development. Catellus remains in place as master development manager, responsible for planning and infrastructure construction. Catellus recently announced that it is being acquired by a Prologis, another publicly-traded real estate investment trust, which will assume the development management responsibilities through the current Catellus staff.

3 The Community Facilities District Act (CFD), also known as Mello Roos, authorizes local governments and developers to create CFDs for the purpose of selling tax-exempt bonds to fund public improvements. Subsequently, property owners that participate in the CFDs pay a “special tax” to repay the bonds. See www.mello-roos.com.

4 Also see accompanying articles analyzing Mission Bay’s sustainability and design for discusion of those topics.