What can San Francisco--California's fourth largest city--learn from the state's second largest, San Diego? A delegation of SPUR members went to San Diego in mid-April to find out.

San Diegans speak of the "San Diego Region" to refer to both the incorporated and unincorporated areas of San Diego County. Encompassing 4,261 square miles and a population of 2.96 million in 2003, the region is bounded by Orange and Riverside counties to the north, Imperial County to the east and Baja California to the south. With 1.28 million people (43%), the City of San Diego is the region's largest city by far. Second-ranked Chula Vista has only 200,000. Thus, it should be no surprise that, in the public mind, the city and region are often synonymous.

The City of San Diego's geographic dominance is even greater than its share of the region's population. Its 343 square miles dwarfs Chula Vista's 51, and a diagonal line connecting the furthest corners of the city measures 40 miles. The average population density is a thin 3,723 people per square mile.

By comparison, San Francisco's population of 777,000 is a mere 11% of the nine-county Bay Area, but at 47 square miles, its gross density is 16,500 people per acre, over four times San Diego's. The San Diego Region's other cities are even more thinly settled, leading directly to a host of planning issues including a dwindling supply of buildable land, high and rising housing costs, mounting congestion, and a land-use pattern that is nearly impossible to serve with transit. Like the Bay Area, the San Diego Region is seeing increased commuting beyond its borders in search of affordable housing; southern Riverside County and northern Baja California are the counterparts to Tracy, Fairfield, and Gilroy. The San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) estimates that five to eight percent of employees in San Diego County commute from Mexico.

Over the last 20 years, the region's economy has moved from being dependent on volatile defense spending to a more subdued and diverse growth. Cutbacks in defense spending in the late 1980s and early 1990s led to the closing of major employers (notably General Dynamics) and the loss of tens of thousands of jobs. San Diego's recession was much more severe and long-lasting than the Bay Area's. Forty thousand jobs disappeared, per capita income dropped 14%, and Las Vegas drew away so many construction workers that when the construction industry revived in the late 1990s, contractors were hard-pressed to find labor. The local chapter of the American Institute of Architects lost half its membership.

By good fortune, San Diego was spared the dot-com bubble and bust, though it wasn't for want of trying to attract high-growth technology companies. Qualcomm was the notable exception. Its stock (adjusted for splits and dividends) went from one dollar a share in 1991 to over $150 in early 2000 to $25 in mid-2002 to today's $64--an arc familiar to Silicon Valley investors but with a happier ending than most.

San Diego's major educational institutions (San Diego State University, the University of San Diego, and most importantly the University of California at San Diego) and major research institutes (Salk Institute, Neurosciences Institute) spun off important enterprises in the biosciences which have enjoyed a steady if unspectacular growth leading to significant investments by international pharmaceutical companies. The downside is that job growth has been confined to high-end and low-end jobs, compounding reduced housing affordability.

The region's geographic dispersion is partly the result of the "canyons and mesas" topography that physically separates communities. Ask a San Diegan where she lives, and she is more likely to give the name of one of the City's 44 official communities. How many outsiders realize that La Jolla is part of the City of San Diego? The San Diego Region also has one of the nation's highest proportions of people who live in developments with homeowners associations, sometimes referred to as "invisible governments." Regional issues like the need for a new international airport do not have a constituency.

San Diego has transformed itself from a low-density suburban community to one with a vibrant, high-density residential downtown. Photos by Jeannene Przyblyski.

Two recent changes, importation of water from the Imperial Irrigation District and consolidation of regional agencies, only occurred because of outside pressure. In the first case, the U.S. Department of the Interior threatened to enforce restrictions on Colorado River water; in the second, former State Senator Steve Peace proposed legislation for a radical consolidation, and the community compromised on a less-sweeping reorganization but still one that would not have occurred without an external push.

Politically, San Diego is conservative Republican but with a strong Libertarian cast. Laissez-faire takes precedence over social conservatism. Lesbians represent the Midtown area in the city council and state assembly, with no public disapproval. The negative is a social atomization in which one's own community eclipses citywide or regionwide concerns. Combined with cynicism about government and hostility towards taxation, local governments are more seriously hard-pressed to address pressing infrastructure and social issues than other California jurisdictions, a serious concern during desperate fiscal times.

Perhaps more than other regions in the state, San Diego's city and county governments have shifted the burden of funding the construction and maintenance of infrastructure and amenities from the general fund to developers and special assessment districts. Even something as common as landscaping in street medians is built with developer funds and maintained by maintenance assessment districts. Older communities with little new development and low tax bases make do with crumbling infrastructure.

San Diego's Staying Power

San Diegans are there for many reasons. A surprisingly large number of people passed through San Diego during their military service and decided to stay. Numerous polls have ranked the region's attractions: the weather and the ocean are invariably at the top; everything else is a distant third. Educational institutions, cultural life, and challenging careers register slightly. Perhaps most surprisingly, immigrant communities do not figure prominently in city life; instead, the flood of migrants from Asia, Africa, and notably Latin America mostly flows right through the county to better opportunities in the Los Angeles area. (The ubiquitous Border Patrol may also encourage immigrants, illegal and otherwise, to move on.)

Planning

Major planning efforts are underway at all levels of government. SANDAG is preparing regional land use and transportation plans that attempt to contain sprawl. The county's main transit agency, the Metropolitan Transit Development Board (which SANDAG recently absorbed) continues work on its own "Transit First" strategy, which was adopted in 2002. The County of San Diego is preparing a new general plan for the unincorporated areas, the first time in 25 years that they have been updated.

The planning effort that has gotten the most attention is the City of San Diego's "City of Villages" plan which addresses the city's rapidly diminishing supply of vacant land by maximizing the density of new development and seeking to densify existing communities, particularly where transit and infrastructure are readily available. All cities and counties are obligated to address regional population and employment growth and housing needs, but footdragging is common. San Diego's planning effort distinguished itself by setting the principle at the outset that it would accommodate all of its forecast growth. Already housing almost half of the region's population, the city was expected to accommodate a similar proportion of the growth.

Planning Department staff knew that existing communities would be skeptical of dense new development and allocated fully 40% of the housing increment (over existing plans) into the 2.2-square-mile downtown area. Even with this preparation, publication of a draft map of opportunity sites was greeted by outrage by some communities, and a draft of growth allocations was withdrawn before it reached general circulation. As always in such debates, objections were led by traffic and parking, but there was strong skepticism about the City's ability to upgrade infrastructure to meet current needs and those of new residents. Single-family communities were wary of mixed-use development and multi-family housing, in part because of San Diego's unhappy history of higher-density housing in the form of the "Huffman Six-Pack," named after the developer Ray Huffman--San Diego's counterpart to San Francisco's "Richmond Specials." Privately, there were also fears of low-income and minority households and supposed social problems.

During the administration of Mayor Pete Wilson, the city council created an independent agency to implement downtown planning and the redevelopment plan. The Centre City Development Corporation (CCDC), like its Baltimore model, is governed by its own board of directors, appointed by the city council. The intent was to distance downtown redevelopment from city hall and to inculcate a pro-development culture. CCDC's first major success was the Horton Plaza Shopping Center, which opened in 1985. To bolster demand, almost 500 condos were completed at the same time, the trolley line was built to the Mexican border, and plans started for the convention center, which opened in 1989.

Shortly after the City began the City of Villages plan, CCDC started to update the 1992 downtown community plan. That plan already called for adding 24,000 units of housing by 2025 for a total population of 51,000. The City of Villages called for yet another 9,000 units.

The 9,000-unit figure was the product more of political considerations than of planning analysis.

The City began the City of Villages plan determined to accommodate SANDAG's growth forecasts, but as resistance to increased density outside of downtown grew, downtown became the solution to a politically awkward problem. The downtown community, for its part, was and is unique among the city's communities in that almost everyone (property owners, business owners, and even residents) welcomed development. If there is a lesson here for San Francisco , it is much easier to focus growth on a limited area where there is a consensus on the benefits of high-density mixed-use development than to persuade skeptical neighborhoods. Like San Francisco , San Diego has district elections. It is difficult to achieve citywide growth objectives when city council members are ready to support their colleagues' objections to infill projects. San Diego 's downtown has had a negligible portion of the population of its council district (in fact, most candidates haven't bothered to campaign there) so the NIMBYism that paralyzes most planning discussions hasn't taken root. CCDC has been careful to educate new residents on plans for new development so that they don't become a new opposition.

Because of the recession, downtown experienced very little development from 1992 to 1998 when CCDC issued a request for proposals that revealed an previously unknown reservoir of demand for downtown living and brought a flood of new housing. Completions rose from 539 units in 2001 to 1,150 in 2002 and 1,771 in 2003, according to CCDC's monthly development status log. As of April 1 of this year, another 252 units have been completed, 3,666 units are under construction and 5,465 are in the permit pipeline. When the community plan update started, the average density of new residential development was 140 units per net acre. To add 9,000 units to already aggressive plans, the community plan update targets 200 units per net acre. To stop (relatively) low density development from occurring while the new plan was developed, the City adopted a minimum floor-area ratio (FAR) of 55% of the maximum FAR in about one quarter of the downtown. With maximum FARs as high as 12, the minimum was set deliberately to force high-rise construction.

Low-rise modernism is the new norm both in free-standing new housing and on the periphery of high-rise blocks. Photos by Jeannene Przyblyski, Heidi Siegenthaler, and David Hecht.

Downtown San Diego is virtually the only area of the region that lends itself to significant transit usage. Countywide, about 3% of peak-hour commute trips are by transit. Downtown, it is in the range of 20% to 25%. Downtown is at the hub of the trolley system's three branches; numerous bus lines traverse downtown or terminate there; the Coaster provides commuter rail service from Oceanside ; and the airport is 10 minutes away. At first glance, it seems logical for downtown to attract the residential development it is experiencing; with transit plentiful and a broad range of jobs and services downtown, car ownership and usage could fall well below other areas. However, there has been very little job growth downtown; instead job growth has been occurring largely to the north in widely scattered, low-density office and R&D parks that are thinly served by transit. Unless new jobs can be concentrated on transit routes, downtown's new population could aggravate the already-heavy south-to-north commute.

Housing

In 1990, downtown had 16,000 residents and 73,000 jobs. On the surface, adding thousands of residents should support the "job-housing" balance, but existing jobs are heavily concentrated in low-paying service industries while most housing (except the required 15% low and moderate-income) is anything but affordable.

San Diego 's housing prices are lower than in the Bay Area, but because of lower average incomes, the housing affordability index is similar. The usual suspects are blamed: limited land supply, excessive regulation, protracted and unpredictable approval processes, burdensome fees and exactions, etc. The latter is a direct outgrowth of Proposition 13 and voters' reluctance to tax themselves for adequate infrastructure and services. Permit fees are set to cover all processing costs. New development pays its own way for streets, utilities, parks and schools. Maintenance of street lighting and landscaping is by specific assessment district.

Many of the planning efforts, including the City of Villages, have made a false assumption that increased density necessarily means more affordable housing, when the opposite is often the case. Parking costs rise as density entails structured or underground parking. Costs also rise as taller buildings are built out of steel and concrete instead of more affordable wood-frame, and high-rises require costly fire protection systems. Higher density can result in cheaper housing where land costs are fixed or written down, but the more common situation is that land price is a function of what is built on it and rises as the value of new construction rises. This is not to question the other benefits of higher-density development such as energy efficiency, critical population mass to support mixed-uses, jobs-housing balance, and transit efficiency, but rather to counsel against false expectations for affordability.

The new wave of downtown development consists mostly of high-rise towers with townhouses at street level. Photos by Jeannene Przyblyski, Heidi Siegenthaler, and David Hecht.

San Diego has had modest success in building affordable housing due to reluctance to burden already-expensive market-rate housing. The City only recently adopted citywide inclusionary housing, and the in-lieu fees have been set so low that little new construction is anticipated. The one success story has been CCDC, which has produced 29% of downtown housing as affordable units compared to the minimum 15% required by state redevelopment law. CCDC has been particularly successful in the construction of single-room occupancy residential hotels (SROs), which most other communities shun because of associations with flop houses and problem residents. In reality, income restrictions and requirements in new SROs are such that only employed persons, often in service industries, can afford the rents; these are the workers in the service industries which are one of downtown's few growth clusters.

There are ongoing policy debates about affordable housing. Is it important that downtown have a diverse housing stock, or is it more cost-effective to spend housing funds in outlying neighborhoods with lower land costs and cheaper building types? It is conventional wisdom that families should be accommodated in both market-rate and affordable housing, but with poor schools, substandard open space and relatively high housing costs, will families choose downtown living? (Today, there are very few households with school-age children except in old, substandard housing on downtown's eastern fringe.)

Downtown Redevelopment

San Diego 's downtown redevelopment program is one of the most successful in the state, and in a field notable for abuses, San Diego has been a model of probity and efficient use of taxpayer money. (In the interest of full disclosure, the state recently questioned the citywide redevelopment agency, of which CCDC is a part, for its interpretation of requirements for replacement housing.) The principal measures of success of a redevelopment program are the increase in assessed valuation and property taxes and a sustainable economy. Too many redevelopment programs pour money into marginal undertakings that cannot function without ongoing subsidies.

Urban Design

San Diego 's laissez-faire and tax-adverse culture has led to a parsimonious approach to the construction and maintenance of public facilities and to a reluctance to impose a positive vision of how neighborhoods function and appear. New communities have strict design guidelines (and homeowners associations to enforce them) and the more affluent older communities such as La Jolla have been very successful in stopping significant changes in the intensity, height and bulk of new development. Downtown San Diego is one of the few older areas that has attempted to articulate a positive vision of both the public and private spheres. The 1992 community plan and zoning (known as the planned district ordinance) have highly detailed requirements for building intensity (floor-area ratio), view corridor setbacks, stepbacks, sun access, building top articulation, etc. Detailed standards target a positive pedestrian experience by requiring active street-level uses, limiting blank walls and curb-cuts, and demanding transparency. Some areas require minimum requirements for successful retail spaces such as ceiling heights, space dimensions, floor elevations, and services.

As in San Francisco , San Diego 's older neighborhoods are identified by their neighborhood shopping streets ( University Avenue in the Hillcrest area, Adams Avenue in Normal Heights , etc.). Downtown San Diego is at risk of repeating a mistake made by San Francisco 's South Beach , which is to scatter retail wherever it fits or is needed to "activate" a dead sidewalk. Retail needs to be concentrated along the routes of heaviest movement and be contiguous.

The astonishing quantity and speed of residential development is attributable to the clarity and certainty of the development regulations and entitlement process. Few projects require discretionary approvals, and design review is limited to the larger projects. A staff of knowledgeable planners and architects understands the building types and development process and insist on high-quality but realistic design. Development permits are issued in weeks instead of the months typical outside downtown. There is no doubt that the pro-development culture of the downtown community makes this possible, but the regulations and structures are in place to provide the predictability that developers crave and allow them to keep down their profit/risk premium. Perhaps most importantly, a master EIR covers most downtown development, and subsequent environmental review is minimal. The lesson is that if the city knows what it wants, communicates it clearly to developers and sticks to it, high quality development will result quickly and economically. When the rules are ambiguous, unrealistic, arbitrary or changeable and there is no certainly that a feasible project will be approved, fewer developers are willing to participate, project costs rise (in part to compensate for the risks of delay or denial), and the process becomes politicized.

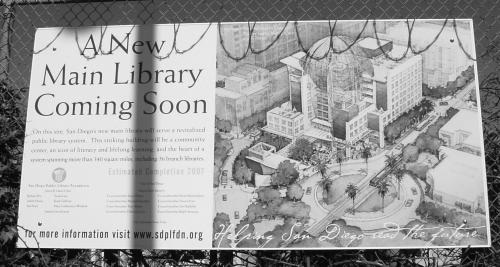

Downtown San Diego 's urban design effort is weakest in the public sphere. Public buildings (notably city hall) are an embarrassment, parks and plazas are grossly inadequate, and downtown's greatest asset, the waterfront, is either inaccessible or unimproved. It is a sad statement about the life of the city that public rallies to commemorate 9/11 were held in the parking lot of Qualcomm Stadium, 5.5 miles from downtown. Two factors are in play: (1) the attitude that any money spent by the public sector, even on improvements that directly benefit taxpayers, is inherently wasted, and (2) the fact that the waterfront is state tidelands and held in trust by the five-city Port of San Diego, an agency that has always emphasized revenue-producing uses at the expense of public amenities, particularly on the San Diego waterfront. By rights, the sizable property tax increment from downtown redevelopment should fund public improvements, but most of the funds have been committed to big-budget projects like the ballpark, new main library or a portion of a waterfront promenade, and new park, plaza and streetscape improvements have been few and scattered. The one unqualified success has been streetlighting. Citywide, the general fund only pays for one dim lamp at each intersection, and whole districts have no lighting at all. Downtown tax increment funds have been used to add four to six bright, high-quality street lights per block, turning downtown from the city's worst-lit to best-lit community. Utility undergrounding has been a mixed success; almost all downtown utility lines have been undergrounded, but the City's franchise agreement with SDG&E is silent on transformers and other such paraphernalia, with the result that sidewalks throughout the City are obstructed by desk-sized boxes.

Sidewalks throughout the city also also littered with backflow preventers"large plumbing assemblies required by the state health department to implement the federal Clean Water Act. San Diego 's water department insists that they be located above ground immediately downstream from the water meter to prevent illegal connections; that places them right in the middle of the sidewalk. If there were an urban corollary to Murphy's Law, it would say that backflow preventers, like transformers, will end up in the worst possible locations unless planners are vigilant and willing to fight the engineers.

The Ballpark

The new Petco Park , home of the San Diego Padres, has received a lot of press coverage outside of San Diego , some of which has been accurate. Several writers have credited the ballpark with the residential boom, oblivious to the fact that the boom started several years before a downtown ballpark was even discussed much less decided upon. Numerous studies of sports facilities have been inconclusive about their economic benefit, and the campaign for the San Diego ballpark was careful to avoid any claims for net job growth or catalytic development. That said, the ballpark did dramatically change the perception of downtown's East Village area. Prior to the decision to locate the ballpark there, CCDC could not persuade developers to even look at East Village , much less risk their money. With the huge commitment of public funds, the East Village has become downtown's new hot spot. A site eight blocks from the ballpark recently sold for $310 per square foot; ten years ago, land in that area ran $30 to $35 per square foot.

The Border

It is only 14 miles from downtown San Diego to the border, by most accounts the most heavily trafficked international border crossing in the world. Over 30,000 Tijuana residents commute to the U.S. every day, and traffic reports on both sides of the border include information on the number of gates open at the San Ysidro and Otay Mesa crossings and the length of the lines. Mexican shoppers spend millions in the U.S. In fact, the first leg of the trolley system was built to carry shoppers to downtown's Horton Plaza Shopping Center and workers to hotels and other service jobs. Downtown San Diego 's largest employment sector is government related, and a major portion of that is in the justice system dealing with immigration and contraband issues.

The main border crossing at San Ysidro illustrates the contradictions in American policy. On the one hand, Mexico and the U.S. border area are tightly bound culturally and economically. Besides the employee crossings, the tariff-free assembly industry (maquiladoras), though battered by Chinese competition, is still Tijuana 's largest employer and entails warehousing and trucking on the U.S. side. Large areas of Baja California and Sonora states ship produce through the crossings to the U.S. (Strangely, most produce is shipped directly to Los Angeles--area wholesalers then shipped back to San Diego retailers.)

Economic integration implies a porous border, but security and immigration policy demand a barrier. Symbolizing the ambivalence, a15-foot tall steel fence runs along the border over hill and gully right into the Pacific Ocean . Border Patrol vehicles pass incessantly, trying to catch people that burrow under the fence. The Border State Field Park , straddling the border and centered on an 1851 monument, was dedicated in 1971 to celebrate the friendship between the two countries. The monument is imbedded in the fence, which is thoughtfully made of transparent chain link for several yards in each direction.

Lessons for San Francisco

Clear development regulations with minimal discretion increase predictably and lower development costs, particularly the risk premium that developers otherwise must add to their profit. Housing is more plentiful, comes on line quicker and is more affordable. Exactions such as inclusionary housing need not discourage development if they are reasonably priced, known from the start and not subject to change.

San Diego 's regional traffic problems have been due to the lack of redundancy in the street and freeway system. The branching pattern of streets means that every trip, even within a neighborhood, has to use a higher-level street. Virtually all trips between communities must use the one or two freeways nearby. By comparison, most cities in the Bay Area have some variant on a street grid, and (with the exception of the bridges) multiple routes between communities.

The San Diego Region has scattered both housing and jobs over the county and into Riverside County and Baja California . The pattern is virtually impossible to serve by transit. Starting with a more extensive transit system, the Bay Area has been relatively successful in concentrating development around transit and has seen significantly higher transit usage.

San Diego voters have been very reluctant to make up for Proposition 13 with new taxes and fees. New development pays heavy impact fees and assessments, but none of the proceeds flow to older communities. Without credible commitments to fund infrastructure, older communities have been reluctant to accept new, higher-density development, even when packaged as "villages" or "transit-oriented development."

The San Diego Region encompasses a single county that is geographically separated from its neighbors by military bases, mountains, desert and the international border. It has consolidated many of its regional infrastructure planning and management programs in a single agency that is pursuing a coordinated strategy of "smart growth" land-use planning, transportation investment, and transit operations. Perhaps more importantly, SANDAG has the power and the will to allocate transportation funding to support regional goals. The Bay Area by comparison has nine counties and many more agencies, largely dependent on voluntary compliance.

To approach the San Diego Region's successes with regional growth and neighborhood planning, San Francisco and the Bay Area will have to resolve tensions over revenue, housing, and community development through policy-making, rather than through the debilitating politics of project approval. Policies on growth and housing affordability need to be set at the regional and citywide level with appropriate mitigations worked out well before deliberations on individual projects begin. Day-to-day planning administration should focus on the quality of development, not on whether it should occur or at what density. Both San Diego and Vancouver (the object of SPUR's last investigation) show that a consensus on development policy can allow the planners and urban designers to concentrate their professional skills on creation of what San Diego Mayor Dick Murphy calls "a City worthy of our affection."