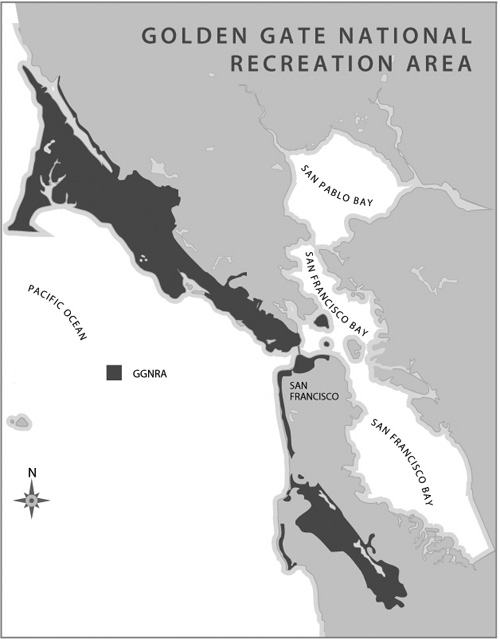

Brian O'Neill is Superintendent of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), one of the largest urban national parks in the world, with over 75,000 acres of land and 28 miles of coastline. The park itself is over twice as large as San Francisco. O'Neill, a long-time SPUR Board member, is recognized for his leadership in the Bay Area environmental community and as an international leader in the field of park management and community stewardship of natural resources. He met with SPUR deputy director Gabriel Metcalf to discuss the park and his role in its management.

Brian O'Neill is Superintendent of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), one of the largest urban national parks in the world, with over 75,000 acres of land and 28 miles of coastline. The park itself is over twice as large as San Francisco. O'Neill, a long-time SPUR Board member, is recognized for his leadership in the Bay Area environmental community and as an international leader in the field of park management and community stewardship of natural resources. He met with SPUR deputy director Gabriel Metcalf to discuss the park and his role in its management.

Doyle Drive is just one example of the transportation issues facing the GGNRA. What are some others?

The park is supposed to be for all the people. But the military installations that were here were really more insular enclaves. Our access challenge is how to open them out, to be more a part of the communities in which they are situated. Our vision is for a kind of seamless link with people in the region--and this larger idea of both water- and land-based shuttle systems to provide part of that connectivity.

In the next year we're going to be coming out with alternatives both for a shuttle system out to Muir Woods and Muir Beach, Stinson and Mt. Tamalpais as well as Tennessee Valley--and also having water-based transportation systems that can bring people from around the Bay and that connect up to all the other, existing transportation systems. Right now, traffic on weekends is as bad as it is during the week. Our goal is to make it be that the choice of coming to the Park wouldn't just conjure up the impending image of sitting in traffic for two to three hours to get out to Stinson Beach.

In the last few years, you have been sharing the lessons of the GGNRA with other park systems around the world. What are they?

Well, one is this whole concept of a park built on partnerships. The GGNRA has dozens of major partners who are critical to how resources are preserved and people are served at the park. But what's really behind it, how do you go about building a partnership culture? What are the success factors that are important to understand and have in place for that culture to thrive and for the partnerships to be properly nurtured? And then, what are the barriers to good partnering--cultural barriers, policy or legislative barriers? And how do you overcome those? And then how do you build, within an organization, a culture that wants to build ownership in the community over the values of the park?

An agency like the Park Service has its strengths and its Achilles Heels. We were born from the military in 1916, so we've carried forth a lot of the traditions. This whole concept that --the best way to do it is to do it yourself? is part of the culture of the organization, but we realized that, to be successful in today's environment, it's about collaboration and partnering.

We've actually found, through trial, error and growth on our own basis, and looking at other examples across the country, that there are probably about 20 success factors that are absolutely key to a partnership reaching its full potential. But they really start with the ability of someone to let go of control.

The second area is that the Park really has become well known for being innovative about alternative funding sources because the needs of this park were so enormous it wasn't feasible that we would ever get but a small part of those needs met through congressional appropriations. We've developed what we call a "stewardship investment strategy," which guides how we think about generating the resources we need.

The third area is one that has really challenged us--how do you connect the mission of the National Park Service and the values of a park like ours to an increasingly diverse America? Many members of our society have never been exposed to the National Parks and what they're all about. So how do you create the elements of an organization going into the future that can build a sense of ownership of those values? How do we inspire people who have come to the park to be able to take the lessons there and apply them at the neighborhood level?

The fourth area people are interested in has to do with how you position the parks in the marketplace, and create an awareness of the parks. We've been working with a dream team of pro-bono help, to help us understand how do we create that identity and brand. How do we connect people to that brand? People aren't going to support a National Park unless they've become emotionally connected to it. We've realized that the emotional connection and sense of ownership of the values of a place really require what we call "incremental hooking." Which is really a series of incrementally deeper and deeper engagements that you provide on an individual basis, on a group basis, on a corporate basis.

And more than any other partnership, you rely on the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy.1 We realized that you can't do all those things: you can't build a partnership culture, you can't do comprehensive constituency building, you can't do a whole marketing and branding program, and you can't engage the community at a deeper level to stewardship without having a non-profit partner who has the dexterity, flexibility, and ability to do things that government just has a hard time doing. So we realized that the park was going to be dependent upon our ability to build a very strong non-profit partner whose sole purpose was to be able to help us think about how the real promise and potential of the park could be realized. This is the Golden Gate National Park Conservancy, which was established back in 1981.

What brought you to the GGNRA?

I particularly wanted to work in this environment because I felt that it is one of the most complex units of the National Park system. I knew this job would force us to invent different ways of connecting to the community, different ways of finding resources--and that the park was continuing to grow. I felt this was a good innovation lab for the Park Service in that we had just about every kind of issue it deals with nationally, in one way or another, and that we had a community that was very environmentally advanced in its thinking and action. We felt that if it couldn't work here, it would probably have a very difficult time working elsewhere. This was a safer environment for innovation because the community had such strong support for parks and open space, and a willingness to get involved.

And I think we've learned Americans aren't so prone to reach out to look for best practices. Other countries are much more proactive in looking at models elsewhere and how they could apply. So we're trying to get the Park Service here to be more open to seeking out new and different ways of being able to meet the challenges that we face. I love that work, and I consider it really important that each of us who occupy a senior position in the National Park Service give a certain amount of our time in helping others, learning from others, and looking at how we apply that both on a national level and locally.

What does the Presidio Trust mean to the broader context of the Park system? Is it a model for other parks or is it the product of a particular time and place?

When the Presidio Trust was going to be established as a Government Corporation by the US Congress back in 1986, we were fighting to save the Presidio as a unit of the Park System. The Park Service developed a master plan that looked at different governance models that could work for the Presidio and out of that work we had proposed a partnership arrangement to create a Presidio Trust. Congress took that idea and reworked it, and there were some major requirements that had not been envisioned by us. The most important of that was the fact that it needed to be self-sufficient after 15 years of operation, which put a whole different level of burden of responsibility on us.

So I think the Park Service is immensely respectful of what the Presidio Trust challenge is in order to meet that financial obligation. But I think we've been equally insistent that it could be accomplished in a way that fully protected the resources and provided for program content. And I think if there have been differences over the years, it's been how you draw that balance and how you make it economically self-sufficient as required by Congress, but in a way that allows some wonderful institutions carrying out some terrific programs to occur there, so the site becomes distinctive from the quality of the program.

As we found at the GGNRA, there are many properties that simply cannot and should not make a good business deal. Not every building and not every structure at the Presidio can be seen as a business opportunity. Their ability to be reused will never be achieved until you find a partner who has the passion to create a program idea, who is willing to raise the funds to assist in the rehabilitation of the buildings.

The Park Service's role in those is more of a facilitating role to help communities define the potential of a place. It's just not feasible for the Park Service to own all of this land when the real goal is to advance the cultural protection of a site. How do you see the cultural landscape and how do you work with all the community of interest to preserve it? In order to really commemorate these special places, we have to do it in partnership with the living communities that are connected to the place today.