In considering the design for the new Doyle Drive and the process it has gone through to get this far, it is useful to reflect on the history of road design in America. Early settlers, with horse and wagon at their disposal, out of both necessity and convenience built roads along ridgelines and stream valleys in concert with the topography.

When Thomas Jefferson had the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 surveyed, a rational Cartesian method of one-mile grids was established, intended to result in political equality, giving each family an equal parcel of land. But of course size did not mean equality, with vastly different topography, water supply, aspect, and accessibility from parcel to parcel. However, this engineered system of laying out property and physical facilities by transit and level was to have a lasting effect on American civil design.

It took Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903), the founder of the profession of landscape architecture, to react against this domination by geometry. Olmsted understood that the landscape architect had a crucial role in both the preservation of rural values and the provision of urban services. And he understood that his designs had to work for new technologies and lifestyles not yet imagined.

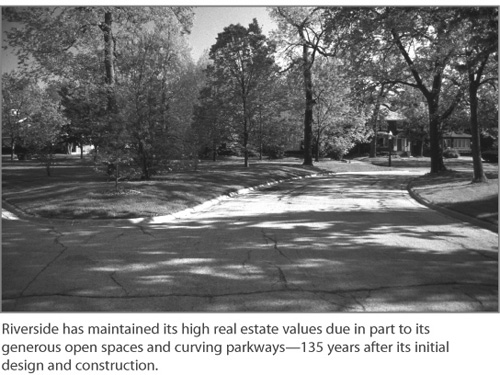

In the period 1868 through 1870, Olmsted and his partner, the architect Calvert Vaux, designed a 1,600-acre planned community west of Chicago called Riverside. A key concept in their design was a system of curvilinear streets that followed the contours of the land, which reduced grades and saved money on "cut and fill" for road construction. In addition, Olmsted wrote of the social benefits of such a street system: "As the ordinary directness-of-line in town streets, with its resultant regularity of plan would suggest eagerness to press forward, without looking to the right hand or the left, we should recommend the general adoption, in the design of your roads, of gracefully-curved lines, generous spaces, and the absence of sharp corners, the idea being to suggest and imply leisure, contemplativeness and happy tranquility [sic]."

Because Riverside was a suburban bedroom community, Olmsted recommended a shaded parkway connecting Riverside with Chicago, knowing that workers commuting to the city would benefit from a more leisurely carriage drive. In addition, he saw it as beneficial to "a healthy civic pride, civic virtue and civic prosperity." With only a few miles of this parkway constructed, the model had been set.

With the construction of the Ocean and Eastern Parkways in Brooklyn in 1870, Olmsted and Vaux conclusively demonstrated that parkways could both carry substantial traffic and provide pleasant settings for different activities even as traffic swiftly and safely moved along them. Over 130 years later, these two urban boulevards designed for horse and carriage have successfully adapted to changing traffic requirements while maintaining and enhancing the surrounding properties.

Until the mid-20th century, streets and roads had multiple purposes--they were places to be, not just places to move along as quickly as possible. Certainly, Baron von Haussmann knew this when he was building his 19th century boulevards in Paris: witness the culture of the flâneur, the boulevardier, and the sidewalk café, all notable Parisian institutions, born out of a culture of walking, less for transportation than for celebration and enjoyment of the city. But in America, these kinds of environments hardly exist anymore.

Today the word "parkway" has been corrupted to mean just about anything, from a straight urban street with a planted median, to any wide road so designated by a real estate salesperson.

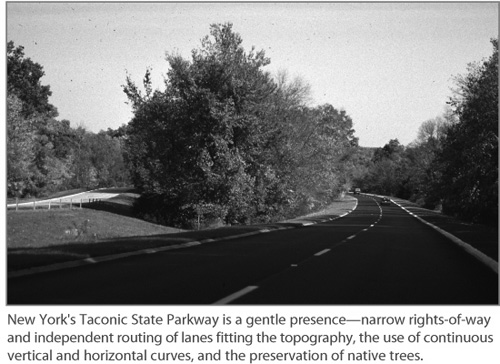

Used correctly, the term "parkway" means a land area dedicated to both recreation and the movement of vehicles--not just a road, but a park that contains a road. It is limited access, and the lanes are sited in relation to the topography, not in relation to each other. The roadway becomes a series of continuous vertical and horizontal curves with no straight lines, much like two ribbons laid upon the landscape. The emphasis is on the driving experience, not a mathematical time-distance calculation, which can only result in straight chords and a boring and often unsafe driving experience.

Beginning in the 1920s, the Westchester County (NY) Park System developed a number of county parks connected by parkways--the Bronx River, the Saw Mill River, the Cross County, Hutchinson River, and the Peekskill parkways. They all had as a purpose making the driving experience as pleasant as possible, focusing on an ever-changing series of vistas, with landscape blending seamlessly into properties beyond. And they became a model for others throughout the country, including major highways such as New Jersey's Garden State Parkway (1956) and the New York State Thruway (1957). These two especially are relevant because they were designed for the high-volume car and bus traffic that we have today on Doyle Drive.

What all of these examples have in common is that they were designed as collaborative efforts between landscape architects, architects, and engineers. This collaborative design system fell apart as highway design became the exclusive domain of highway engineers. Landscape architects were relegated to "prettifying" the engineered designs--adding trees and irrigation. With the passage of the Defense Highway Act of 1956 and a series of subsequent federal funding bills, rigid engineering criteria required that the chosen route be the least time-distance solution. In other words, flat and straight. The engineers' "green book" (the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials' handbook) standards ruled all decisions. Jersey barriers replaced gracious landscaped medians, and design speeds increased to levels way beyond posted speeds, while driving speed increased proportionately. Huge cuts and fills and concrete retaining walls laid heavily on the land. What resulted, of course, is a network of roads that carry an enormous volume of traffic at high speeds, but that are environmentally damaging, mostly ugly, numbingly boring, and, in fact, many are believed unsafe because they encourage 90 mph speeds even as they lull you into boredom.

In recent years, the freeway builders have begun to take aim at the gracious parkways from earlier in the century. ("Doesn't meet federal standards. Too curvy. Too narrow. Too slow. Narrow shoulders. Level of service too low.") The response to each complaint has been design changes to increase the speed for most cars most of the time--straightening curves, widening lanes, and adding shoulders. Anyone who has driven the pre-1956 eastern parkways knows the difference--the driving experience can actually be beautiful and fun as well as efficient.

As a place that has essentially grown up post-World War II, California has freeways that are some of the worst. But there are exceptions--the best being I-280 which shows the deft hand of landscape architect Lawrence Halprin and architect Mario Ciampi. The roadways hug the rolling hillsides and the curving bridges are uncommonly graceful.

The existing Doyle Drive, however, fits into the category of the worst. Because it was crossing the Presidio, then a military base, the Army insisted that it be elevated, allowing no interchange between civilians and military. Its one function was to carry vehicles across and away from the Presidio quickly.

But fortunately, change is at hand, beginning with the passage of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA) and its offspring, the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21). TEA-21 recognizes "context-sensitive design." That is, each highway project is unique, due to its unique environment and unique community. Once again, the contributions of the landscape architect are being recognized and a new emphasis is being placed on designing roadways that are fast, safe, beautiful, environmentally responsible--and cheaper than the old heavy-engineering approach.

That one of the first examples of this "new old-style" parkway should be a replacement for Doyle Drive is appropriate, as it is crossing the Presidio, which is part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, land by definition dedicated to recreation. The old elevated eyesore, with unsafe traffic geometry and failing structural conditions, is neither adequate nor appropriate to its park location. One hundred years after his death, Frederick Law Olmsted would be proud of the proposed new parkway.