ABAG's growth projections are treated as inevitable. Their reports sometimes talk passionately about the negative consequences that continued sprawl will have for the region... But ABAG's projections, like MTC's Regional Transportation Plan, show only one official future.

What we need is not one set of "projections," but alternative futures we can choose between.

--SPUR Newsletter, September, 1999

ABAG, the Association of Bay Area Governments, is a voluntary association of local governments. It has no authority over any governmental body. The one "mandate" beyond what local jurisdictions all agree to have ABAG do is that the state legislature has delegated to ABAG the task of developing population growth projections for the region. These population growth projections--which break down current Bay Area populations by city and county, ethnicity, household size, and employment rates, among others, and project changes over the next 30 years--are intended to guide local governments' decisions about how much housing they need to produce. But the local jurisdictions aren't bound to follow them, so they go unused as policy tools and become little more than curiosities.

In June of this year, ABAG released its Projections 2003, which forecasts population through the year 2030. Projections 2003 was supposed to be different than anything ABAG has done before.

Following the publication of SPUR's article in 1999, ABAG contracted with SPUR to develop a plan for doing growth projections in a new way, one that would not simply predict sprawl and call it inevitable. ABAG conducted workshops with citizens and elected officials in every part of the Bay Area, where staff planners presented the scope of the population-growth challenges we are facing as a region, and worked with regional stakeholders to develop alternative approaches to managing this growth. This "Regional Smart Growth Vision" process became the most serious popular discussion about the future of land use and transportation in the Bay Area in more than a decade.

Projections 2003 is the end result of these four years of work. The projections are different from past projections, but ultimately not different enough.

SPUR's argument was that the core problem with ABAG's methodology was that it presented only one set of projections, with one outcome. What the region needs is alternative possibilities--all of them realistic, in the sense that they evolve from present-day realities, but each alternative representing a different set of choices that we could make over the next several decades.

Said another way, we argued that ABAG should make policy-based projections instead of trend-based projections. The agency should use the population-growth-projections exercise as an opportunity to model how different policy choices we make today will shape the region over the coming decades.

Projections 2003 does not do this. It again presents only one set of projections. It does not spell out how different choices we make today will result in different outcomes for where people live and how they get around. In this fundamental sense, the new projections are business as usual.

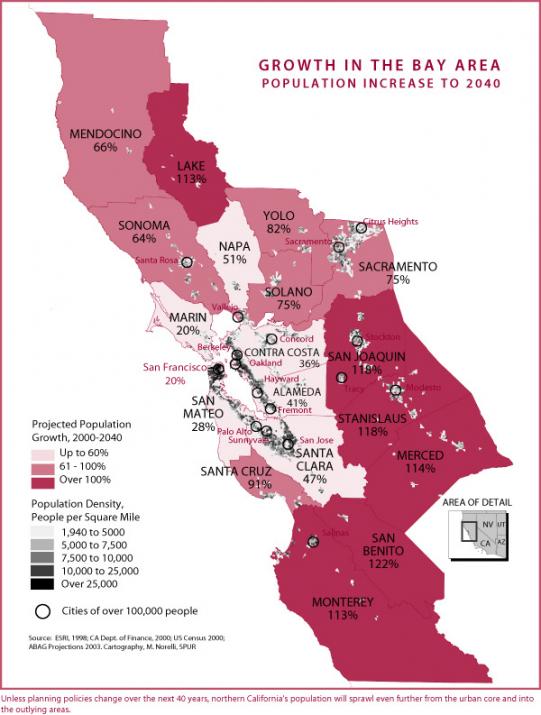

They do diverge slightly from past projections in one sense: they assume that land-use policies across the region will change slightly, that housing production near existing transit lines will increase over past projections. These assumed shifts toward infill development mean that Projections 2003 predicts 126,350 more housing units in the Bay Area by 2030 than the "base case" scenario, which goes without the assumed smart-growth policies. This translates into 214,000 fewer employed residents commuting into the Bay Area from housing in the Central Valley, north of the Bay Area, or south of the Bay Area.

ABAG's planners and demographers are generally very progressive. They want a region that does not sprawl endlessly, that makes alternative transportation viable for more people, that brings down housing costs. It is probably a step in the right direction that the new population projections rely on more optimistic assumptions about infill development. But ultimately, Projections 2003 fails. It does not spell out what policy actions would be necessary to make their more optimistic assumptions a reality. It does not spell out how different policy actions would result in less sprawl, or more. It does not help us understand how our choices today will affect different regional forms by 2030. As citizens and policymakers, we need to see alternative futures modeled, and understand what actions will bring us toward each possibility.