Regional governance is virtually untried in the United States. If you're looking for a regionally elected official from a metropolitan area, I'm the only one that there is. That doesn't mean that it can't work other places, but the conditions for success are very particular--what works in Portland doesn't necessarily work in other places. When I'm asked about what other regions can learn from Portland, I'm reminded of the perils of trying to export democracy to Afghanistan, for example. Every place has its own history and its own peculiar circumstances.

Conditions that Made Portland Ready

The Oregon system began in the 1970s when Tom McCall was governor. Tom McCall was not Ronald Reagan. Attitudes towards government in that time were different. A unique set of circumstances came together in the 1970s, not only in the Portland region, but statewide. The leadership in the region and in the state created a set of institutions and foundational values at that time that have now endured for 30 years, and have been built upon progressively. But the Portland miracle can't all be attributed to the quality of our leadership; I would highlight five characteristics of the Portland region that helped make our governance system possible. First is the relative homogeneity of the region. The gap between the central city and suburbs, economically, ethnically, and racially is relatively small. This is not a value judgment, but practically speaking it is much harder to get people together in a more diverse region.

The second condition that existed and still exists in the Portland region is the relative youth of our political institutions as well as the relatively short time many people have lived in the region. Compared to many East Coast cities, we don't have the same kind of entrenched political "machines." A high proportion of our residents were born outside of Oregon. And I think they often come to government with less of a sense of parochialism than in some parts of the country. California, of course, has a relatively young body politic as well. This is an important thing to consider when you're asking people to not only identify with a given suburban municipal jurisdiction, but to identify with the broader region--there needs to be some sort of flexibility or willingness to change.

The third condition in the 1970s was a real tradition of policy innovation--an openness to new ideas. Partisanship didn't matter very much. The state legislature passed a number of measures that are unthinkable now. We passed the bottle bill, the first refundable deposits on bottles and cans. We passed a bill that made all the beaches in the entire state open and public property. So when Governor Tom McCall proposed ideas that in other states might have been unthinkable, Oregonians were ready.

A fourth factor that enabled Portland to understand the need for regional governance was the importance of agriculture and forestry, and the proximity of these practices to the urban area. There were many conflicts at the rural-urban edge that were very visible to both urban and rural voters. Both of them had reasons to be at the table and supporting land-use planning. Forestry and agriculture represented economic interests that were threatened by urbanization. Which meant that rural legislators, who are often conservative, understood the need for stronger planning to protect these livelihoods. At the same time, the urban legislatures that were predominantly Democratic had constituents who cared about their beautiful vistas not far from home. The urban voter going to the beach for the weekend or seeing Mount Hood in the winter drives through incredible landscapes that they cherish. Those voters were pressing for landscape protections for very different reasons than the economic motivations of farmers, but they were a very strong motivation nonetheless. The result was that both Republicans and Democrats, both rural and urban voters, supported the land-use planning program in the 1970s. One of the challenges for us now is how to sustain that broad political support given that it has gotten more difficult for Republicans and Democrats to work together and given the fact that forestry and agriculture have declined in economic importance.

A fifth and final condition that is worthy of mention is the fact that people could see very clearly that there were urban problems that were going unsolved. There is a tremendous amount of inertia in government institutions and in the political world generally. To change course really requires a popular perception that things need to change. In the 1970s it was very obvious to people in their everyday lives what those threats were. People saw downtown Portland dying. They saw the air quality getting worse--one day out of three during the summer Mount Hood was obscured because of smog. And they saw suburban encroachment on nearby rural land. They didn't like it, so there was a sense of crisis of people saying they had to act.

The Emergence of True Regional Planning

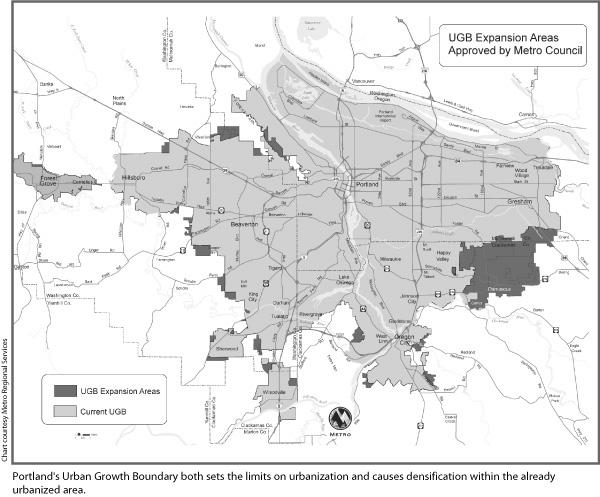

The style of development in the Portland region up through the late 1980s was no different than anyplace else in the country, in terms of the urban form and per capita consumption of land. For the first couple of decades that Portland's urban growth boundary was in place, I think most people thought of it simply as a way to contain the geographic extent of urban settlement. The focus was on protecting farm and forest land from urbanization. Very little attention was paid to what urbanization itself was like or creating great urban places. In the 1990s that changed for a couple of reasons.

One was the renewal of the sense of crisis, based in large part on population growth. The projection was that over the next 20 years there would be 500,000 more people in the metropolitan area, which in 1990 was just over a million people--and that if the per capita consumption of land (a measure of the density people are living at) continued to follow the patterns of the 1970s or the 1980s, the urban growth boundary itself would have to be expanded by about 50 percent, infringing on those landscapes that people treasure. That lead to a realization that the urban growth boundary itself was no longer a sufficient tool. Unless we changed the way we were actually using land inside the boundary, the urban growth boundary would be expanded. That pushed people to understand the need for stronger regional planning, because there was a recognition that everybody needed to accommodate some of the growth. Things happening in one jurisdiction affected all the others. If one jurisdiction refused to accommodate its share of the growth, that would lead to the urban growth boundary having to expand for everyone.

Through a whole discussion about what the world would be like in the year 2040, most people came to understand the need for more density, for clustering development around centers, for trying to incent more redevelopment of older parts of town, for investing in the transit network. Now, you could say that people everywhere basically understand these concepts. But what made Portland different is that we were willing to make adherance to these principles binding. This was the critical thing that happened in the early 1990s: we invested the Metro Council with the authority to do functional land use planning.

The makeup of the Council ensures broad representation: the City of Portland has two seats, each of the three counties' commissioners are on the policy advisory committee, the port commission has a seat, then there are seats for smaller cities who represent one another on that. In terms of our activities, it's a strange collection of functions that have accumulated over the years that in many ways don't seem to have anything to do with each other. We run a convention center, an expo center, and a performing arts center. We run the zoo. We embarked on a voter-approved green-space acquisition measure, so the Metro Council owns about 10,000 acres of natural areas and green spaces. We operate two solid waste transfer stations and have the contract for the land fill, as well as transportation and land use planning.

Why would the 24 regional cities give up those prerogatives to the Metro Council? It's very unusual to give up authority to another level ofgovernment. They retained zoning and issue permits, but it's an unprecedented degree of oversight that the Metro Council has over those 24 cities. Why did that happen?

One reason was that the localities were already used to state oversight of their land use planning. They were willing to give up some local control to a regional entity partly because they already had less local control than perhaps cities in other states already do.

A second reason was that they had a lot of experience working together on transportation issues, and an understanding that they were dependent on joint regional solutions for all the transportation issues that mattered to people. So because there are so many connections between transportation and land use, the move to do some land use planning on a regional level was an extension of the transportation planning we were already doing.

Another reason the local jurisdictions were willing to go along with a more empowered Metro stems from the old idea that when you're asking people to give up something you have to give them something in return. Ironically, many of the suburban jurisdictions wanted to be involved because they felt that if they were not, the City of Portland was going to dictate everything, and the other 23 didn't want to be dictated to. They saw Metro and the Metro Counsel as a neutral body that would help balance that the dominance of Portland. The city of Portland, by contrast, wanted to be part of something regionally because it saw a lot of growth going to the outlying areas and recognized its interdependence with the other towns. Local officials were also willing to publicly embrace Metro because the local officials were given very important checks and balances within the system. Every two weeks there's a policy advisory committee that consists of mayors, fire districts, transit districts, and the port authority that come to the Metro Council and advise us. In our charter they have to approve of major things that we adopt. We can't "take over" a function that local government is providing unless that body tells us we can.

These were some of the reasons we were able to get functional planning authority.

The Results

How do we assess the results? One way is that agricultural land has been protected to a greater degree in Oregon, including in the metropolitan area, than other parts of this country. All kinds of acreage statistics will show you this. The economics of agriculture have changed--growing berries is not as profitable as it once was, while nurseries and wineries are a lot more important--but the fact remains that there is viable agriculture in the state, and near urbanized areas.

Another positive result is that development that began in the late 1980s is far less consumptive of land than prior to the adoption of functional planning. Partly that's a result of land prices going up because we've constrained land supply with the urban growth boundary. But part of it is directly attributable to our land use regulations that require higher densities.

We have not done as well on the investment side. The Oregon system is very legalistic and regulatory, focused on what do we not want to have happen. We have not been as shrewd on spending on things that we do want to have happen. While the Metro Counsel does blend land-use authority and transportation-planning authority, there hasn't always been the partnership that we need to have with some of the agencies, primarily the Department of Transportation. In many ways they still behave as if they were the high commission of the 1950s in terms of how they spend money. So we need to be doing a better job, particularly with state investment.

The Bay Area has very different circumstances from ours, but I'll suggest a couple of lessons we've learned in Portland. First, is that you have to provide real incentives for local jurisdictions to be at the table--some reasons that citizens will benefit from a stronger regional government. Second, you need to find something that by definition cuts across boundaries, whether it's a zoo that serves the entire region or it's solid waste--services that people want that can only be done on a regional basis. It may be related to water quality and the bay that everybody shares. It may be a trail system that everybody shares. But it should be something visible that can only be done regionally and that can help you develop a sense of regional stewardship and regional citizenship.