ALL THE SQUARE'S A STAGE

By April Philips, ASLA

William Shakespeare wrote, “All the world is a stage.”

Entertainment is not a new concept, yet our 21st century society is more determined to be entertained than any other culture in recorded history. Statistics show that we are becoming a celebrity-obsessed and voyeuristic society. As our hectic lives are expanding, our need for relaxation is growing. Yet, increasingly, we do not have time to relax. Public spaces are getting harder to find. Many exist in a state of decline. As the population and economy grow, so too grows the pressure to build buildings rather than to create public spaces. Societal pressure is just one reason that public space needs to be cherished, preserved, enhanced and created. As society’s needs evolve and change with every generation, our public spaces need to be reevaluated and redesigned when the changes result in a space that no longer functions for the society in which it exists. This entails embracing the belief that there is a fundamental value to open space that goes beyond the dollar amount it costs to build or maintain.

First, we need to understand how today’s desire to be entertained affects our design of public space. Entertainment has come to represent both being the performer (the active role) and watching the performance (the passive role). It has become intrinsic to our daily life. The role of any public space should be to serve society and create spaces for people of all races, ages, shapes and abilities. Designing places where people can enjoy sitting, conversing, eating, reading, meditating, watching others, lingering, gathering, or walking through provides an experiential opportunity that people have craved through the centuries. Each of us experiences public space at a personal and ultimately primitive level, enjoying our own private theater. We are delighted by and come to expect the spontaneous performance, including our own. Experiential space provides us with memories. Memories are one of the key factors that elevate a space into a place. If a designed space cannot achieve the status of place, then the design will falter and become irrelevant. I call this the Zen component of public space.

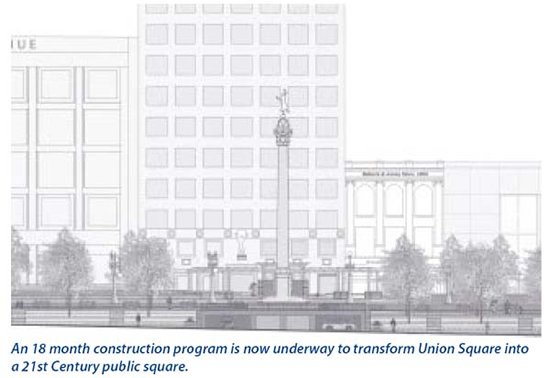

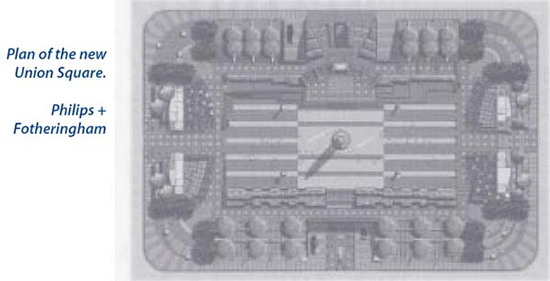

At what point will a beloved space become unbeloved? A sense of safety is certainly necessary for a place to be vital and attract users, but that is only one component to a successful public space. Public spaces need to incorporate a more cosmic flexibility. Understanding the context, the functional components and the spontaneity of how people use space can be the key to discovering new ways of providing the flexibility today’s public spaces require. Allowing for duality of use is an important criterion in determining flexibility. Creating spaces that allow for graceful addition or subtraction over time as society’s needs change is also important to the long term success of a public place. These are some of the key ideas we have built into the redesign of Union Square.

Another critical element for success is choice, such as in providing a variety of seating opportunities that allow individuals to choose what they want to sit upon as well as where they want to sit when entering a space. Choice includes creating both active and passive opportunities and allows for all kinds of behavior, thus becoming democratic public space.

While there are many other important components to public space, we need to understand that ultimately, public space provides a city with the opportunity to meet the needs of its people. A successful space brings people back to it like a good book. Successful public space talks to people and expresses ideas. Perhaps the most important idea for public space is that the design be about an idea and people will desire to discover it again and again. D.H Lawrence said it best: “For human beings, as for flower and beast and bird, the supreme triumph is to be most vividly, most perfectly alive.” Public spaces of the 21st century need to express the duality of our urban desires in order to create our urban memories and make us feel alive.

TAKING CARE OF PLACE

By Michael Fotheringham, ASLA

To be successful, public spaces such as Union Square are dependent on the ability of the design to be both secure and beautiful, harmonizing the functional and structural qualities of common open space. Enriched materials and spatial flexibility are essential to fulfilling public expectations that civic spaces be designed for a wide variety of entertaining events. Our experiences redesigning Union Square and observing the evolutionary changes of comparable public plazas across the nation have confirmed that neglected public space is doomed to abuse and decline. Neglect comes in two forms: lack of physical maintenance, and inadequate levels of scrutiny and containment of misbehavior. Observation of the Union Square site has yielded a surprising revelation: our tolerance (or perhaps ignorance) of bizarre misbehavior in public places is undermining our trust in the commons. Whether out of fear or apathy, certain vulgar, disrespectful and illegal acts occurring each day go seemingly unnoticed, unreported. Yet most of us who witness these misbehaviors are offended by such acts. Visitors to the old Union Square confirmed that there was a fear of and discomfort from walking through the place, even during the day, reported by both men and women. The preponderance of panhandling, illegal and dangerous skateboarding, graffiti, vandalism, public indecency and the occasional vulgar outburst in the Square raised questions about the viability of public parks and plazas as places of refuge from stressful city life.

About 18 months ago, members of our office observed a most disturbing behavior occurring on the streets surrounding Union Square. From our conference room windows, four stories above Powell Street, we observed a male in his thirties, casually dressed and carrying a valise, following closely behind a woman. From the position and stillness of his valise, it became obvious that there was a camcorder hidden in the valise and he was videotaping the woman from the waist down. He would follow her for a minute or so, then abruptly change direction and follow another woman. We noted his posture, the close distance he maintained behind his victims and particularly the stillness of the valise as he walked. This violation of right to privacy presented an ominous situation. Over the next few days, we observed him again, and also saw him at street level. Further investigation into the law revealed that it was, at that time, not illegal to videotape someone without their knowledge, nor was it illegal to upload these images to the Internet, which was likely this person’s intent. (Since January 2000, it has been illegal to videotape someone in public without their knowledge.) This shocking behavior brought to focus how tenuous a sense of security and safety can be.

Democratic public space, a place facilitating free speech without fear of state sanctions, is a rare and recent element of urban design in free world cities. Informally, the need for human interaction in groups, small or large, remains a primitive, universal, spontaneous and necessary urge. City and village form has historically designed places for interaction, consciously or otherwise. The foremost consequence of individuals gathering at the commons is to communicate the evolving formation and exchange of common sense, common understanding, common vision, and consensus, while tolerating divergent thinking. However, allowing bizarre and antisocial behavior to occur without some form of correction is a disservice to the general public. The constituencies of public spaces must commit to taking care of the place. Good design must reward the best behavior and discourage the worst behavior. The successful design process brings into focus the essential needs and comforts of the respectful public as prime client. Long-term viability of public parks and plazas will require a new form of sustenance oversight.