This article is the third in a three-part series examining how Oakland can close its structural deficit and move toward fiscal solvency and economic growth. Part 1 looked at the evolution of the city’s budget woes. Part 2 examined the city’s budget-setting, spending, and revenues. Part 3 outlines long-term priorities that the city should focus on to close its structural deficit.

By May 1, Oakland’s interim mayor will roll out the proposed budget for 2025–2027. Given the many revenue constraints on the city’s General Fund (covered in part 1 of this series), coupled with rising costs and significant long-term liabilities (covered in part 2), Oakland’s mayor and city council won’t have any easy choices when it comes to balancing the budget this year. While newly elected mayor Barbara Lee won’t be sworn in in time to release the proposed budget, she will be charged with setting Oakland on a stable path to closing its structural deficit and positioning the city for fiscal sustainability, representing a pivotal moment for Oakland. This article describes what needs to be done to reach that moment.

As outlined in part 1 of this series, Oakland’s budget challenges didn’t happen overnight. In 1978, Proposition 13 capped property taxes and reduced local government revenues by 60%. To compensate, Oakland has relied on voter-approved special taxes, but these taxes have not been sufficient to cover rising personnel and operational costs, leading to persistent budget shortfalls. In the wake of the Great Recession the city adopted strong financial policies and, with the help of a good economy, actually achieved surpluses from 2016 to 2019. But then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, creating the largest budget shortfall in Oakland’s history — until now. During that global crisis, the city depleted its Rainy Day Fund, suspended financial policies, and used one-time revenues to respond to the urgency of the moment.

Oakland’s current fiscal crisis is part of a larger pattern seen in many U.S. cities struggling with the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Like San Francisco and San José, Oakland is facing declines in tax revenue, driven by a slow recovery in tourism, retail, and commercial real estate. Part 2 of this series showed that though revenues continue to grow year after year, they fail to keep pace with rising costs for health care and operations. Unfunded pension liabilities — retirement benefits owed to former city workers — further constrain the city’s budget. Over the past several years, Oakland has waived its fiscal policies, delayed hiring, and relied on one-time funds provided by the federal government as well as on the unrealized sale of the Oakland Coliseum to close its deficit.

Underlying the city’s fiscal distress are some deeply rooted structural issues that will take strong and creative leadership to fix. With a growing lack of trust between and among Oakland leaders, city staff, Alameda County, and the public about how resources are being managed to deliver services, the city lacks a long-term plan to fix the structural deficit. Instead, it resorts to short-term decision-making that keeps it from moving toward fiscal stability, much less economic growth.

As Oakland navigates this moment of leadership transition, there’s an urgent need for a collaborative and creative approach among policymakers, administrators, labor unions, and the community to reduce spending and grow revenues, ultimately ensuring that the city maintains critical services for residents and positions itself for long-term financial stability and growth.

To close its structural deficit, Oakland must focus on three priorities.

Number 1, city leaders need to come together and commit to sound financial practices and align on a budget stabilization plan. Number 2, Oaklanders need to consider reforms to Oakland’s governance structure to support more effective decision-making. And number 3, everyone—not just city leaders but also business and labor leaders, county and regional partners, and residents—needs to engage in long-term thinking to create economic prosperity for all Oaklanders.

Commit to Sound Financial Practices

After the Great Recession, Oakland developed strong fiscal controls and strengthened financial policies to guard against the impact of future economic downturns. It did so by collaborating with labor unions to make short and long-term spending reductions, by implementing other cost-cutting measures, and by adopting and adhering to sound financial practices.

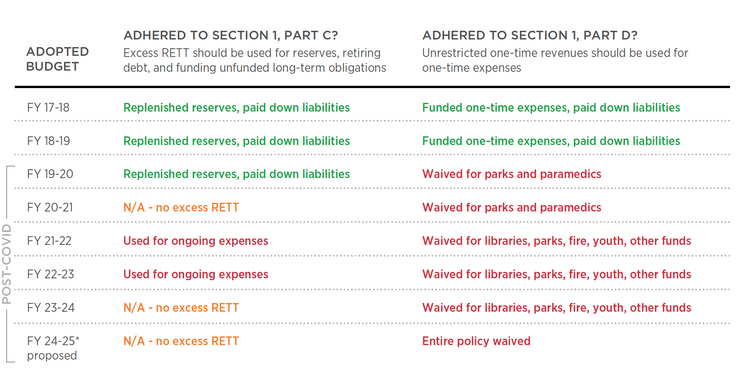

The city’s ability to move from deficits to surpluses in the 2016–2019 period hinged in large part on its adoption of the Consolidated Fiscal Policy, which provides a detailed framework for developing and adopting the city’s final two-year budget. The policy requires that one-time revenues be used to pay for one-time expenses. It also requires the city to use excess real estate transfer tax revenues in good years to shore up reserves, speed debt repayment, and pay down unfunded long-term obligations like health care for retired employees. But in 2020, the city began waiving these policies in efforts to prevent layoffs and retain staff through the pandemic.

To achieve fiscal solvency, the city needs to get back to following its own financial policies. Failure to do so has undermined the confidence of credit rating agencies and lenders, all of which recently downgraded Oakland’s credit rating and lowered its outlook from “stable” to “negative.” In February, S&P Global Ratings warned it could further lower the city’s rating if Oakland exhibits “prolonged inaction or ineffectual policymaking to contain the structural budget deficit, significantly weaker reserves or liquidity, or outsized reliance on one-time budget-balancing measures.”

The City Has Resorted to Multiple Overrides of Its Consolidated Fiscal Policy Since 2020 to Maintain Services

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the city has used excess real estate transfer tax (RETT) revenues and one-time funds from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) to maintain services. CARES funds ended in 2020, and ARPA funds ended December 31, 2024.

Source: Oakland Budget Advisory Commission, Recommendations for FY 24-25 Mid-Cycle Budget, June 9, 2024, https://cao-94612.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/documents/FY24-Mid-Cycle-Budget-BAC-Recommendations-Packet.pdf.

In 2021, SPUR’s Making Government Work report recommended that the city create an independent Controller’s Office responsible for enforcing spending policies, particularly those laid out in the Consolidated Fiscal Policy. The controller would also help keep the budget in balance by determining how much money the city has available to spend and by denying spending proposals if the funds were not available to pay for them.

Reform Oakland’s Governance Structure

Strengthening Oakland’s finances will take the strong and sustained leadership of the city administrator, but Oakland’s current governance structure — which differs from that of every other city in California — undermines such leadership. Oakland’s city administrator reports to the mayor, but the city council sets policy priorities and the budget, and the mayor has no power to veto the city council’s legislative and budgetary actions. Torn between the priorities of the mayor and those of the city council, the city administrator is unable to effectively develop and execute a long-term strategy. To solve this problem, Oakland will need to conduct a formal review of its charter with the aim of developing a ballot measure to clarify the role of the mayor, creating clear lines of authority and accountability, and ensuring that the rest of the government is structured to support the design.

Oakland’s unique governance structure is a mix of two more typical forms of local government, mayor-council and council-manager. Many larger cities have some form of a mayor-council system, while council-manager forms of government are typical of smaller cities and of counties. In a mayor-council or “strong mayor” system, a mayor who is directly elected by the voters acts as chief executive, and a separately elected city council constitutes the legislative body. The elected mayor is granted almost total administrative authority, with the power to appoint and dismiss department heads. In a council-manager government, the mayor chairs the council, which appoints a chief executive officer, typically called a city or county manager, to oversee day-to-day municipal operations. Oakland, while categorized as a mayor-council form of government, is neither a strong-mayor city, because the mayor lacks veto power over the budget and legislation, nor a council-manager system, because the mayor does not serve on the city council.

In light of inevitable cuts to services, the city also needs to look at how to more effectively allocate staff and resources to deliver core services. Oakland is required by law to close any deficits before passing a budget. To do so, it often carries forward any unspent funds to the next fiscal year by freezing vacant staff positions or by allowing for attrition and not backfilling positions. While preventing layoffs, this strategy has led to unmet staffing needs, service deficits, and unimplemented priorities.

As of November 2024, Oakland’s staffing vacancy rate was 22%. With nearly one-quarter of staff positions unfilled, the city needs to be realistic about staffing levels and eliminate positions that are not funded. It should conduct a staffing analysis to reorganize the workforce based on updated assumptions. Then, it will need to make some hard choices about what it will continue to do, ensuring that its top priorities and core services are adequately resourced.

The City Administrator’s Office has begun to develop Oakland’s first strategic plan to improve city operations. Through that effort, the city should look at how operations are funded and identify opportunities for structural improvements, including cross-departmental collaboration or the merging of duplicative functions. Upgrading technology and improving cross-departmental processes in core functions — for example, budget management, staff management, contracting, permitting, and grants administration — could make all city operations more effective.

To succeed, this effort needs to be resourced. Moreover, the budget and the strategic plan should be tied to specific, measurable community outcomes — such as reducing police response times or increasing affordable housing — and it should be integrated with an equity analysis to ensure fair distribution of resources and accountability for results.

Grow Shared Economic Prosperity for All Oaklanders

Closing Oakland’s structural budget deficit and moving toward shared prosperity will require partnerships with the community, business, labor unions, the county and the region. Oakland should align goals with partner agencies, dedicate staff time to collaboration, and increase communication and accountability for results.

Oakland generates more revenue than most neighboring cities through a diversity of revenue streams. In recent years, voter-approved parcel taxes and other special taxes have helped grow revenues for the city’s General Fund. However, these decisions also constrain the city’s budget flexibility by restricting revenues to fund specific services or service levels. Voters have been generous in approving taxes to support critical services, but they have lacked information about the potential trade-offs that arise when the city faces budget shortfalls. While new revenues should be part of the toolkit for developing a holistically balanced budget, a balance needs to be achieved so that residents and businesses are not overburdened.

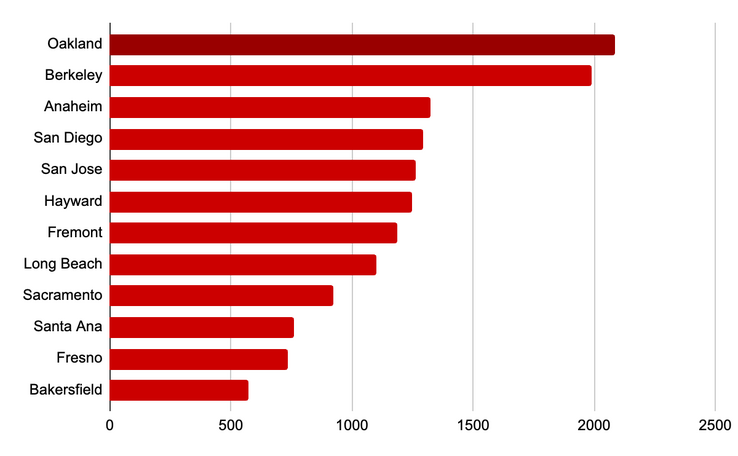

Among a dozen California cities of a similar size and with similar services, Oakland collected the highest amount of per capita tax revenue in FY 2022–23.

Source: SPUR analysis of California State Controller's Office, Cities Financial Data, FY 2022-23

To attain a more sustainable fiscal position, the city should focus on growing its tax base — and attracting new taxpayers — in a way that enables economic prosperity for all Oaklanders. In light of the city’s growing structural budget deficit, the city must identify creative strategies to bring new revenues into the city in partnership with outside organizations, including those in the private and philanthropic sectors.

The city’s Economic & Workforce Development Department is currently working on an economic development action plan to guide its work. The plan has the opportunity to create economic development and land use strategies that attract and maintain businesses, grow revenues, and facilitate outside investment. In addition to improving the city’s fiscal position, these strategies should prioritize sectors that will (1) produce high-quality jobs that match the education and skill sets of the people who live in Oakland and (2) help close racial unemployment and income gaps. To realize the plan, Oakland must invest in the work of the Economic & Workforce Development team and engage a cross-sector group of community stakeholders to support the city in growing Oakland’s economic base.

The structural budget deficit cannot be closed in this budget cycle, but the foundation for that goal can be laid. As the city contemplates the difficult decisions that will have to be made to pass a balanced budget, SPUR will be looking to the city leadership to weigh short-term actions against long-term stability, strengthen city collaboration with labor unions and Alameda County, eschew use of one-time revenues for ongoing expenses, seek cross-departmental process and technology improvements, and resource performance management and economic development work.

During May, Oakland will hold budget town hall meetings in each council district. These meetings are a great opportunity for Oaklanders to learn more about the mayor’s proposed budget and to share their priorities with council members. For more information or to sign up for town hall meetings in your district, visit oaklandca.gov/budget.