This is the first of two blog posts exploring lessons and policy ideas for how to support San Jose’s South First Area arts district. We’ll continue the conversation at our public forum Keeping SoFA SoFA on February 27.

Great cities are not measured only by their commerce but by their unique sense of place and round-the-clock dynamism — the kind of qualities that arts and culture provide. The arts have deep roots in San Jose, and the sector has been growing. Americans for the Arts estimated the 2015 total economic impact of the nonprofit arts sector in San Jose at $191 million dollars, up from $122 million in 2010. There are more than 2,000 arts related businesses in San Jose, including 319 performing arts businesses, 30 museums and 72 arts schools. However, the sector remains smaller than that of other cities comparable in size, such as Indianapolis (population 850,000, arts industry of $440 million) or Forth Worth (population 850,000, arts industry of $450 million). Miami in particular punches above its weight in the arts, with the total industry growing from $576 million in 2010 to $750 million in 2015 despite a population of only 450,000.

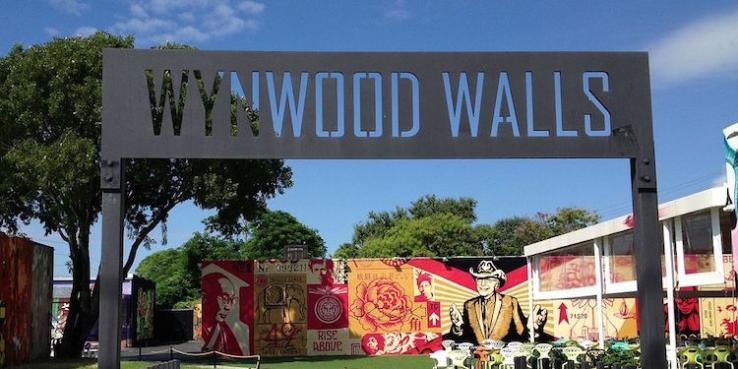

Arts and culture are flourishing citywide in Miami, but the growth of one neighborhood in particular offers lessons for San Jose on the promises and pitfalls of a burgeoning arts scene. Like San Jose’s South First Area (SoFA), Miami’s Wynwood District has become known for its successful mix of galleries, nightclubs and restaurants. And like SoFA, Wynwood today faces threats brought on in part by its own success.

Over the last three decades, Wynwood rose rapidly from abandoned warehouses to international arts destination thanks to sustained investment and support from state and local government, visionary developers, philanthropic organizations and an established local arts scene. Today, Wynwood is in danger of becoming a victim of its own success, as rising property values and rents risk driving away the very artists that made it such a unique and attractive place.

Wynwood’s Beginnings

Starting in the late 1980s and into the 1990s, artists began moving into the formerly derelict warehouses of Wynwood and repurposing them as studios and galleries. Early arrivals such as the Bakehouse Art Complex (established in 1986 in a former large-scale bakery) and the Rubell Family Collection (established in 1993 in a repurposed DEA-confiscated goods warehouse) would grow to become neighborhood anchors of the arts, and in turn attract both art and investment into the neighborhood.

Wynwood has benefitted from public funding of the arts at both the state and local level. The Florida Department of State’s Division of Cultural Affairs provides many types of grants to artists, institutions and organizations. Their General Program Support Grant awards grants ranging from $1,000 up to $150,000. Since eviction and displacement are some of the greatest threats to arts communities, the State of Florida has issued cultural facilities grants up to $500,000 to enable arts and cultural organizations to purchase, renovate or build new facilities and venues.

In 2004, voters in Miami-Dade County passed a bond dedicating more than $550 million to construct and improve cultural facilities. While the money raised by this bond primarily went to larger and more established institutions like the Miami Museum of the Arts, it helped kindle the general resurgence of the arts in Miami that attracted smaller galleries and independent artists to Wynwood.

Private foundations also played a key role in supporting the arts in Miami. The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation launched its Miami Arts Challenge in 2008 to strengthen the development of arts and culture in South Florida. In the most recent challenge, more than $2.8 million was granted to 36 different artists and organizations, including Wynwood’s Screening Room multimedia exhibit.

While public, private, and philanthropic funds have been a boon to the growth of Wynwood, insightful developers and neighborhood stakeholders have been the biggest driver of the transformation of the district into an arts destination. David Lombardi, president of Lombardi Properties, was originally attracted to the Wynwood area because of its proximity to downtown and the cheap price of its existing warehouses. When he arrived in 2001 looking to purchase a presumably abandoned warehouse, he found 20 or 30 young people looking at art and drinking wine.

This chance encounter became the prototype for Lombardi’s Roving Fridays, in which he would invite artists every Friday to occupy unused space in a warehouse he owned. DJs spun records, Bacardi sponsored free drinks and Lombardi handed out pamphlets for his live/work lofts, advertised with the tagline “anything goes.” Roving Fridays eventually evolved into the Second Saturday Art Walk, a monthly event that features art openings in galleries, restaurants and shops, advertised as “Miami’s largest block party.” Lombardi was not the only major developer to open his properties to artists and the public. Tony Goldman saw in six abandoned warehouses the potential for a giant outdoor canvas for street art, and in 2009 opened the Wynwood Walls outdoor exhibition space. Graffiti artists and muralists were invited from around the world, and today a portrait of the late Mr. Goldman by Shepard Fairey (of “Hope” and “Obey” fame) looks down benevolently on the many visitors to Wynwood.

Zoning Catches Up — And Brings Further Change

In 2015, the Wynwood Business Improvement District successfully lobbied the City of Miami to create a new zoning overlay in Wynwood. This new zoning district, termed Neighborhood Revitalization District-1 (NRD-1), codified the shift in Wynwood from light industrial and warehouse uses to a mixture of housing, businesses and galleries. In its regulation of building height, streetscape and parking, and in the establishment of a public benefits trust fund, the NRD-1 is very similar to other cities’ zoning code, except that it is administered by a private entity, the Wynwood BID. While the BID collaborated with the Miami Planning Department and design firm PlusUrbia on the rezoning plan, the BID alone allocates funds from development impact fees.

In addition to changing industrial zoning to mixed-use commercial, the NRD-1 contains a host of regulations to create a walkable neighborhood and to encourage art in Wynwood. Art galleries and live-work spaces are permitted without case-by-case review, allowing for faster approval and construction. Though the district plan still includes parking minimums, the NRD-1 allows developers to pay a relatively cheap in-lieu fee as an alternative to building onsite parking in order to incentivize consolidation of parking in structures and encourage walking.

The NRD-1 also includes a height bonus to encourage greater density and fund affordable housing and public open space. The bonus allows for two to three additional stories beyond what is ordinarily allowed; in return, an additional fee will be levied on the bonus area and placed in a Public Benefits Trust Fund administered by the BID. Though it has only been two years since the NRD-1 was instituted, according to Joseph Furst, chair of the BID, nearly all new developers have taken advantage of the height bonuses and offsite parking incentives.

By virtue of its location, cultural momentum, public support and visionary investment, Wynwood has become one of Miami’s premier arts destinations. However, as rising popularity begets rising land values, Wynwood is in danger of becoming a victim of its own success. Warehouses that were sold for $40 per square foot in 2000 are now valued at between $1,500 and $2,000 per square foot. The rising cost of Wynwood is driving many of the founding arts institutions away from the district in search of cheaper rents to the west and north.

Though Wynwood has had many mechanisms to attract artists, there have been fewer to retain them. Artists characterize the displacement as “devastating,” and even developers lament that not enough is being done to maintain the artistic character of Wynwood.

The ink is hardly dry on the NRD-1 and already a new zoning overlay in Wynwood has been approved to allow for a 10-million-square-foot Americas-Asia Trade Center and International Finance Center with 24-story towers. Though some cheer the thousands of jobs the center may bring, others are concerned that this will further threaten the vitality of the neighborhood.

Parallels in San Jose

With a number of large-scale developments proposed throughout downtown San Jose, including in SoFA, the city should consider which policies will not only grow and attract but also preserve and protect arts and culture in areas like the SoFA district and greater downtown.

Despite SoFA’s current reputation as an arts-oriented district, there is no formal designation or protection to retain the unique qualities of the community. To continue to grow and prosper throughout the coming wave of change, San Jose should learn from Wynwood’s successes — and its failures. The city would be wise to consider policies to ensure that the center of innovation is, indeed, preserving and supporting its creative economy.

We will explore policy ideas for San Jose and SoFA in a follow-up blog post and at our upcoming public forum Keeping SoFA SoFA. Join us for the conversation on February 27.

Special thanks to Applied Materials for supporting this research.