Alongside all of the formal programs to create affordable housing in San Francisco exists an under appreciated, but potentially important,component of the housing market: units that cost less because they are small and efficiently designed, and in many cases do not come with a parking space.

Housing that is affordable “by design” could become a more important part of San Francisco’s middle-income housing strategy, something to be encouraged to supplement nonprofit, 100 percent affordable projects subsidized with public funds and inclusionary housing units subsidized by private developers. This is a housing type that benefits the lower middle class rather than the truly poor, but it is precisely in this middle income stratum of the market that San Francisco has been least successful in serving. Given that San Francisco’s median home prices have hovered between $750,000 and $800,000 over the past year, and that the City’s inclusionary housing program creates units priced between $200,000 and $250,000 , there is a need to create units priced somewhere in the middle that don’t require public subsidy.

Currently, the Planning and Building Codes make it extremely difficult to build housing that is affordable by design. This is primarily due to density controls, overly prescriptive courtyard and unit exposure rules, and minimum parking requirements in the Planning Code, as well as Building Code limits on the number of stories allowed for wood-frame construction. The result is that most of the city’s moderate income housing stock is in older buildings, constructed before current code provisions went into effect. We believe that some private developers would build affordable “by design” units in some locations in the city if doing so were not essentially prohibited, as it is now.

In 2007, SPUR convened a task force comprising architects, developers and policymakers to explore strategies to reduce the hard “bricks and mortar” construction cost of new housing. In general, this means designing units that are smaller, more efficient, or have fewer amenities. The goal is to enable housing that can be brought to market at prices affordable to households earning between 120 percent and 150 percent of San Francisco median income. That translates to between $77,000 and $96,000 for a family of two and between $96,000 and $120,000 a year for a family of four.

This article, resulting from the work of the task force, contains SPUR’s recommendations to enable the construction of housing that is affordable by design. In particular, SPUR recommends that the City should:

> Regulate building density by height, bulk and setback requirements, not by limits on the number of units allowed.

> Stop requiring parking in new buildings.

> Stop regulating bedroom counts.

The Landes is an example of a five-story woodframe building over two stories of concrete, a common construction type for Seattle, but not San Francisco.

> Enable a greater range of wood-frame buildings to be constructed by allowing housing at the ground floor of podium buildings and greater flexibility in the code to facilitate a fifth story of wood-frame construction.

> Allow developers to fulfill their inclusionary housing requirement by providing a greater percentage of their units at middle-income price points.

> Modify requirements for courtyard widths and rear-yard setbacks to allow for greater design flexibility in locating common open space.

Recommendation #1: Regulate building density by height, bulk and setback requirements, not by limits on the number of units allowed

The right way to control the size of buildings is to rely on height, bulk and setback requirements, not by limits on the number of units allowed. This manages the impacts of buildings on the streetscape and the skyline. However, in much of San Francisco, we also regulate building size through limiting the number of units that can be built within that building envelope. Very often, it would be possible to fit more units within the allowable height and bulk, but because the total unit count is restricted, there are strong financial incentives to build larger units in order to fill the allowable zoning envelope, which results in larger, more expensive units.

Again, the main way to make a unit cost less is to make it smaller and more efficient. The simple change of regulating building size by height and bulk instead of limiting the unit count would encourage the development of more small units instead of fewer, much larger units. This has the added benefit of dividing (or “amortizing”) certain fixed costs, such as the cost of land, by more units, further driving down the cost of each unit in the project. That being said, we understand that smaller spaces need to be designed to be as livable as possible. In general, higher ceiling heights and good exposure help to improve the livability of smaller spaces.

Recommendation #2: Stop requiring parking in new buildings

SPUR already has written extensively on the relationship between parking requirements and housing cost. Because parking costs so much to construct (between $40,000 and $75,000 per unit in San Francisco), it adds to the cost of the housing unit. Requiring units to include a parking space increases the cost of construction by that amount. By eliminating the requirement to construct parking (and by selling or renting parking spaces separately from housing units), greater affordability can be achieved. Clearly, if a developer were trying to create a housing type with smaller units targeted to moderate-income households who would otherwise not be able to afford to stay in the city, many of those units would not include parking.more bedrooms. While SPUR strongly supports the policy goal of retaining and attracting families to the city, we do not believe that mandating the construction of multi-bedroom units achieves that goal. The requirement for multi-bedroom units adds to housing cost, while not necessary resulting in the housing of more people.

Recommendation #3: Stop regulating bedroom counts

Many people are rightly concerned about the loss of families from San Francisco. Some advocates believe that one way to keep families in San Francisco is by requiring the construction of “family sized units” — that is, units of two or more bedrooms. While SPUR strongly supports the policy goal of retaining and attracting families to the city, we do not believe that mandating the construction of multi-bedroom units achieves that goal. The requirement for multi-bedroom units adds to housing cost, while not necessary resulting in the housing of more people

The truth is that the city is filled with multibedroom units — most of the traditional Victorian building stock — but those units often are occupied by unrelated adults. There is no evidence that multi-bedroom units in new developments are being occupied by families, so by requiring multiple bedrooms, the City simply may be requiring singles and couples to have offices and guest bedrooms. In other words, from a policy perspective, requiring multibedroom units fails the basic test of targeting: The benefits do not accrue to the intended beneficiaries. At the same time, this strategy raises the cost of housing for everyone. The only way to make the city more family friendly, from a housing perspective, is to solve the aggregate housing problem. The government should reverse course on the current trend of forcing units to have more rooms, and let buyers and renters make their own trade-offs between location and space consumption.

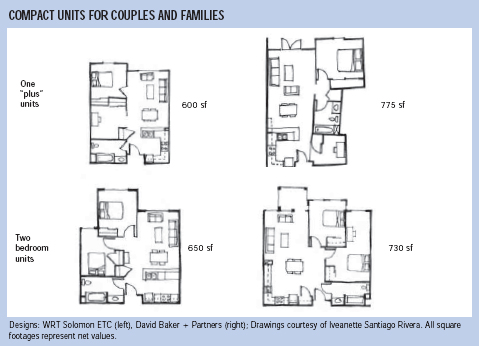

One option to increase the availability of affordable family housing is to change the inclusionary housing requirement to one that would require 15 percent of the total square footage (not of total units) of a project to be priced at below-market-rate levels. The BMR square footage could be concentrated in all two- and three-bedroom units within a project, instead of applied proportionately to the unit mix within a development. In other words, fewer units in a project, but more two- and three-bedroom units, would be offered at below market rates. One additional possibility for adding new non-traditional, multi-bedroom units to San Francisco’s housing stock is to look more closely at “one plus” units, where the second bedroom does not share all the characteristics of a full bedroom but could be used for sleeping. These unit types employ sleeping alcoves or offices that function as a separate bedroom. These onepluses come in all shapes and sizes and are being developed throughout the Bay Area. They are already in place in many existing buildings,often described as “junior twos.” The City could consider allowing one-plus units to count toward some of its two-bedroom count requirements.

Finally, through many of the changes recommended in this paper, more compact two bedroom units could be created and brought to market at more affordable price points.

Recommendation #4: Allow flexibility in the code to facilitate an additional story of housing in wood-frame buildings and housing at the ground floor of podium buildings

The Building Code is at once more restrictive and more flexible than the Planning Code. Because it is based on model codes developed in an extensive peer review process and then adopted by the state, the Building Code cannot easily be changed. However, building officials have the authority under the code to approve alternative construction methods that deliver equivalent protection of health and safety, especially as they are related to the specific needs of the jurisdiction. With this provision in mind, SPUR recommends the Department of Building Inspection and Fire Department study and adopt two possible alternative construction methods that would effectively facilitate the economical construction of additional units on any given parcel, thereby contributing to affordability by design. Although any alternative methods must be approved on a case by case basis, the City could provide the development community with guidance as to acceptable alternative methods by publishing policy guidelines.

Method #1: Housing at the Ground Floor of Podium Buildings

One of the most common building types for new projects in San Francisco is four stories of wood frame housing over a concrete ground floor with parking and retail (a “podium”). The building code section that allows this type of construction does not permit housing in the ground-floor podium. Some jurisdictions, Oakland included, have developed local guidelines that allow and actually encourage housing at the ground floor.

In addition to allowing more units on the same area of land, there are other obvious benefits to this strategy: In locations where mixed-use development that includes ground-floor retail may not be appropriate, it would activate the street edge and bring “eyes on the street” to increase neighborhood safety.

Method #2: Enable an Additional Story of Wood-Frame Construction

The Building Code requires relatively onerous measures if a builder wants to add a residential story to the typical four-over-one configuration described above. Again, other jurisdictions, namely San Diego and Seattle, have adopted code standards to make an additional story of wood-frame construction feasible while maintaining the equivalent fire and life safety (see the modification to Type 3 construction recommended below).

As of 2007, the new building code will allow four-over-one buildings up to 60 tall. A five-over-one would fit within this height, but only by having a 10-foot tall ground floor. Ten-foot-tall ground floors are common in new buildings, but we believe that taller, 15-foot ground floors make new buildings more graceful — in fact, more similar to well-loved older buildings.

In many parts of the city the Planning Code allows buildings to be 65 feet tall. By amending the building code to facilitate the economical construction of five-over-one buildings in neighborhoods already zoned for this height, the City would encourage more affordable density.

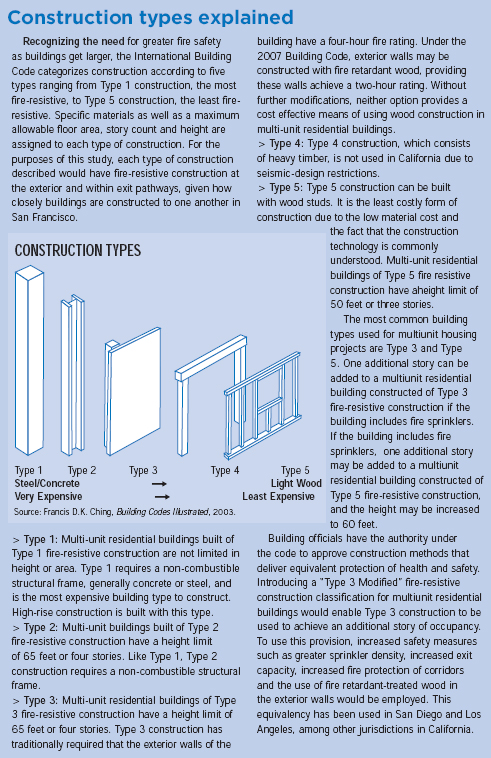

Additionally, in order to facilitate the construction of additional stories of housing in a wood-frame building, SPUR recommends modifying the Building Code to make Type 3 construction more flexible.

Type 3 construction allows additional building height and an additional story of occupied space compared to Type 5 construction, but without the large construction cost premium associated with Type 1 construction. The code definition of Type 3 construction presumes a masonry building exterior with a wood frame interior structure, which is not a cost effective construction technique in a seismic zone. Modification of the requirements of Type 3 construction to allow the use of wood framing in exterior walls, as has been done in some California jurisdictions, would allow builders to cost effectively take advantage of the 65-foot height limit proposed in many areas of the city by providing an additional floor level of housing.

Recommendation #5: Allow developers to fulfill their on-site inclusionary housing requirement by providing more units at middle-income price points, rather than fewer units at moderate-income price points

San Francisco’s inclusionary housing law requires 15 percent of units in new developments to be affordable for households earning 100 percent of the San Francisco median income, assuming that those units are built on site within the project. The requirement increases if the units are built off site or if the developer pays an in-lieu fee to the City rather than building the units directly. We propose that the City consider allowing developers to fulfill the inclusionary housing requirement by providing a greater number of units at 150 percent of the SFMI, rather than fewer at 100 percent of SFMI. This can be done in a way that is revenue-neutral — meaning that the cost to the developer would be equal to the current inclusionary options.

SPUR has analyzed the affordable “by design” strategies discussed here in the context of the historically industrial areas of San Francisco. We found that in places where some additional height was conferred, unit size was reduced and density controls were eliminated, many more inclusionary units than the standard 15 percent could be brought to market at prices affordable to households earning up to 150 percent of the San Francisco median income. One of the central findings of this analysis is that the pricing of units is highly sensitive to unit size, meaning the bigger the unit, the less affordable it is to middle-income people. The analysis also is sensitive to mortgage interest rates and the percentage of household income used to cover housing costs. Giving developers the option to make more of their units available at middle-income levels (as opposed to fewer units, but ones that are affordable to people with even lower incomes, as is necessary under the City’s current inclusionary housing ordinance) is something that the City should explore throughout San Francisco.

Recommendation #6: Modify requirements for courtyard widths and rear-yard setbacks to allow for greater design flexibility in locating common open space

The Planning Code specifies the amount of open space that each dwelling unit should have. That requirement can be met through provision of common open space that is available to other residents. Common open space can be provided in an interior courtyard, provided that the courtyard is a certain minimum area, which must be increased as the height of the building area facing the courtyard increases. Starting with a four-story building, the size of the courtyard is increased by some percentage over the minimum requirement. One way of providing more building area would be to keep the minimum area requirement of the courtyard, but reduce the amount by which the courtyard must be enlarged as the building gets taller. The City also could allow the requirements for common open space to be met elsewhere, say on the roof. Another alternative would be to move to a performance standard that requires reasonable privacy separation while still providing design flexibility.

Rear yards generally are required to represent 25 percent of the total lot area at the rear of the lot. This sometimes serves to support existing mid-block open space, but in other instances it does not. In some locations it may be desirable to replace rear-yard requirements with a lot coverage maximum, allowing project sponsors the ability to do courtyard buildings or other designs that are appropriate for the building’s location. This is commonly found in planned unit developments and could be used successfully on smaller parcels as well.

Conclusion

Affordable “by design” housing has been an important part of San Francisco’s housing stock for decades. By making a few key changes to San Francisco’s planning and building codes, we have the opportunity to encourage the creation of new middle-income units — without additional public subsidy.