Read the complete strategy >>

Uncertainty and delay are deadly to the efficient production of housing, both affordable and market-rate projects. Uncertainty in the approval process means more risk for developers, investors and lenders. And that translates directly to higher costs to developers for both equity and debt, leading to less housing being built and ultimately higher costs to housing consumers.

Uncertainty also simply chases many would-be housing developers away. When there is no assurance that a housing project of a certain size will be approved, many developers will not undertake the significant up-front expense and time to go through an uncertain approval process. This is especially the case in California, where compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) is extremely time-consuming and expensive and must be completed before a project can be approved.

An unduly long approval process also directly adds to the cost of producing housing by increasing land carrying costs (the interest a developer pays on the cost of land) and other “soft” costs (architectural, engineering and legal fees).

This chapter suggests several ways that the approval process for new housing in San Francisco can be reformed in order to add certainty to the process and reduce the time it takes to obtain project approval. These reforms, if implemented, would reduce housing costs for the producers of housing, without compromising the public process. Those costs savings should lead to increased supply, which will decrease housing prices and rents.

SPUR proposes four specific reforms the City should implement to expedite and make more predictable the permit approval process:

- Produce neighborhood plans with program environmental impact reports so that individual projects implementing those plans need not undergo their own extensive environmental review process.

- Establish an “Inclusionary Policy” that requires affordable units in all market rate developments to build certainty into the approval process.

- Remove the automatic conditional use requirement for any project over 40 feet in height in all R zoning districts.

- Establish enforceable timelines for the review of residential projects.

Produce neighborhood plans with program level environmental impact reports so that individual projects implementing those plans need not undergo their own extensive environmental review process. UNDERWAY.

Individual neighborhood plans should be developed and adopted that recognize the distinct characteristics of each neighborhood, define the qualities that should be preserved, and spell out what type of new development is desirable and where it should be located. In this way, a consensus can be developed within each neighborhood among city leaders, neighbors and developers as to the desired type and level of housing development in that neighborhood. In this way, housing developers can propose projects that will be accepted by the neighborhood, its residents and other stakeholders.

In conjunction with each neighborhood plan, a master program level EIR (Environmental Impact Report) would be prepared. A program EIR is an environmental review that covers the maximum development potential on many or all sites within a specified area. The advantage in producing this type of EIR is that projected impacts can be dealt with up front. When individual projects are proposed, no separate EIR or negative declaration needs to be prepared because the program EIR has already anticipated it, and general mitigation measures have already been developed. Having a final program EIR in place can shorten the review period of an individual project by six months to one and a half years, thereby reducing up-front soft costs and carrying costs.

Program EIRs are typically prepared when a new area specific plan and/or rezoning is undertaken. Examples include the Van Ness Plan and the Rincon Hill Plan. Their program EIRs allow many projects to pass through the environmental review process in one to two months instead of six months to a year. However, there is no reason that program EIRs cannot also be done for areas where smaller in-fill projects are contemplated.

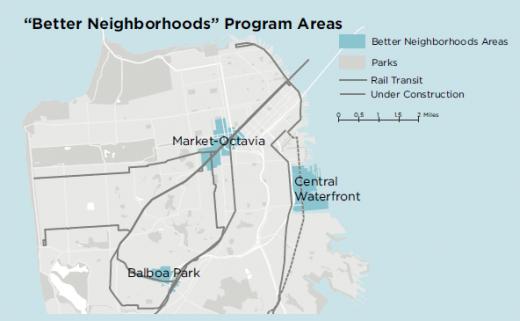

STATUS: We were successful in securing funding for the Department of City Planning starting in the 1999–2000 fiscal year to undertake neighborhood plans, with programmatic environmental reviews, in three neighborhoods: the Central Waterfront, Balboa Park, and Market and Octavia. This program eventually came to be called “Better Neighborhoods.”

Although the Better Neighborhoods planning process has been underway for quite some time, the work has progressed slowly, and the plans are not yet finished as of this writing. See below, "Planning for Neighborhood Change," for more information.

Establish an “Inclusionary Policy” that requires affordable units in all market rate developments to build certainty into the approval process. DONE.

In 1992, the Planning Commission adopted an inclusionary housing policy of requiring 10 percent of all units in new market rate developments to be “set-aside” at below-market rates. (The precise allowable prices for rental and ownership housing under this policy were calculated by the Mayor’s Office of Housing based on percentages of area median income.) Unfortunately, this “policy” was unevenly implemented. Sometimes the Commission would waive the requirement; other times it would impose a different requirement at the last minute. No one knew for certain what the requirement was, or if there was a requirement.

SPUR argued that this type of inclusionary housing policy made sense, if it could be fairly implemented. If the requirement for below market rate units were clear in advance, developers would be able to factor the lost revenue into the price they bid for land, before starting a project. As long as the numbers were reasonable, we believed that an inclusionary housing policy would not stop new developments from going forward.

This approach would create a new source of affordable units that would not require spending tax money, and would even begin to give affordable housing advocates an incentive to support market-rate projects, thereby broadening political support for new housing. The key was to try to maximize the number of affordable units produced while at the same time keeping the requirement low enough that development would still be feasible without giving the developers public money from taxes.

STATUS: After publication of this proposal in the September 2002 SPUR newsletter (“The Better Neighborhoods Program"; available at www.spur.org), we began to work on it through the auspices of the Housing Action Coalition. There was significant disagreement about what the right levels of below market rate units should be—with some activists arguing for numbers as high as 25 percent of the total units, and many developers arguing for numbers well below 10 percent. Eventually, a compromise was reached that sets up a tiered set of inclusionary requirements, depending on whether the project needs a conditional use permit and on whether the affordable units are produced on-site or off-site:

Permitted as-of-right on site: 10%

Permitted conditionally on site: 12%

Permitted as-of-right off site: 15%

Permitted conditionally off site: 17%

In addition, the new inclusionary housing law allows developers to pay an in-lieu fee, equivalent to what it will cost the City to build the housing itself.

The law was passed by the Board of Supervisors in 2001. Certainly not everyone is happy with this outcome, but it appears to be a good compromise that achieves the goal of creating a large number of permanently affordable units while at the same time allowing new development to remain financially feasible. This inclusionary housing legislation stands as a major victory for sound housing policy.

Amend the Planning Code to remove the automatic Conditional Use requirement for high density residential zoning districts.

If the purpose of high density residential zoning districts is to promote high density residential use, then this type of project should be permitted without special discretionary approvals when located in a district that is already zoned to permit taller buildings. Currently, however, all projects of this type automatically require conditional use authorization (and the public hearing process that goes along with it) when they are over 40 feet in height. The purpose of this conditional use requirement is largely to provide design review. If there are no other reasons why a conditional use would be required (such as reduced parking or some other exception), then the design review could be handled at the staff level and no conditional use would be required. The net result of this proposal would be to remove another risk factor in the approval process and shorten the review timeline, which in turn would promote the construction of these types of projects.

Establish enforceable timelines for the review of residential projects.

In some cases, such as for variances, the Planning Department promises a certain hearing date at the time an application is filed. Such timelines should be developed and published for all other types of applications filed with the Planning Department. For complicated projects, such as those requiring environmental review, an approval matrix or branched timeline may be necessary, showing, for instance, commitments to review each aspect of an application within a guaranteed timeframe.

The State of California has enacted The Permit Streamlining Act to address the issue of permit approval delays. The City should develop means to fulfill its obligations under the state law.

The overall logic of this chapter is that we should strengthen planning, rather than have wars over individual projects. When the planning is done right, and it is translated into appropriate zoning, then we should try to remove barriers in the approval process and actually encourage the kinds of buildings we want to be built. If the planning process is working as intended, there will be a great deal of democratic process to develop the vision for how each neighborhood should evolve over time. Once this has happened, we need to make sure the rules are fairly enforced. If a developer is not asking for an exception, but is instead following the rules and the vision contained in a neighborhood plan, we should try to make the approval process as straightforward as possible.

APPENDIX I: Definitions of Affordability

One of the policy tradeoffs the City faces is the goal of making every affordable unit as affordable as possible and the goal of building as many affordable units as possible. For a given amount of money, there is a trade-off between the depth of the subsidy for each unit and the number of units that can be built: deeper subsidies means fewer units.

Various government programs define affordability in slightly different ways. The Mayor’s Office of Housing (MOH) calculates allowable rental and sales prices under the inclusionary law each year, based on HUD data on area median income. In 2003, family median income was $91,500 in San Francisco. Based on this, the allowable inclusionary prices were as follows:

Rental: Must be rented at prices affordable to people who make up to 60 percent of area median income, which means an allowable rent is $1,098 per month for a one-bedroom including utilities.

Ownership: Must be sold at prices affordable to people who make up to 100 percent of the area median income. For a one-bedroom unit, that translates into a purchase price of $282,911.

Source: Mayor’s Office of Housing website (www.sfgov.org/site/moh_index.asp). For maximum rental prices, see “Income, Rent and Price Levels” then “Maximum Monthly Rent By Unit Type.” For maximum purchase prices, see “Maximum Purchase Price Limit Calculations.”

APPENDIX II: The Need For Subsidized Housing

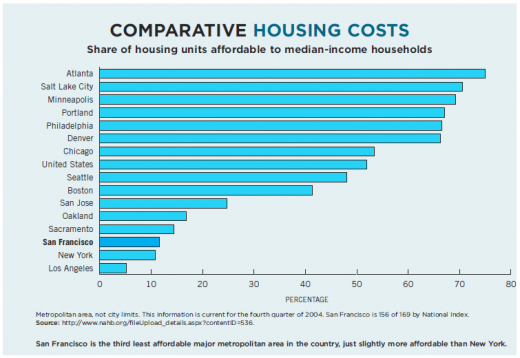

Even if all the ideas proposed in this report were successfully enacted, and even if the cost of housing in San Francisco dropped, we would still need to produce more subsidized affordable housing. The reason is clear: our society is marred by inequalities of income and wealth.

There are two basic ways to pay for subsidized “affordable” housing: 1) use public funds, and 2) inclusionary zoning, which requires developers to build affordable units in market rate projects.

Most affordable housing is paid for with public funds. These can come from the federal, state or local government. The housing can either be built and managed directly by a government agency (the San Francisco Housing Authority) or contracted out to private housing developers. San Francisco is known for having a particularly active non-profit housing sector. The City contracts out construction and management of affordable housing to agencies such as Mission Housing, Bridge Housing, and the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation, to mention just three. Most of the recommendations contained in this report will benefit affordable housing production just as much as they benefit market rate housing: they will simply make it easier to build housing of all kinds.

However, beyond NIMBYism (Not In My Backyard–ism) and the contentious approval process, which affect both market rate and affordable housing, the major constraint on affordable housing is the amount of funding available for it. This funding is, by definition, tax dollars, so it is competing with all the other public funding needs and it has to overcome the anti-tax attitudes that are so prevalent in California. Affordable housing developers need subsidies to purchase land, to pay for operating subsidies if the residents require ongoing supportive services. Affordable housing is not "low cost" housing in the sense that it is "cheap" or costs less to construct. Rather, rents in affordable housing cover a smaller portion of the overall cost of construction, requiring public subsidy to make up the difference. Affordable-housing developers spend a great deal of time and energy piecing together federal, state and local subsidies to make these complicated projects come to life.

Inclusionary housing is another important way to increase the affordable-housing supply because it allows for affordable units to be produced without public funds.

The only way to reduce average housing costs—to make housing more affordable for large numbers of people—is to increase the supply. But it’s important to recognize that there will still be people—the most vulnerable members of our society—who need subsidized, below-market rate housing. We need housing at all income levels.

APPENDIX III: Planning for Neighborhood Change

Because of the work of SPUR and the San Francisco Housing Action Coalition, comprehensive neighborhood planning efforts are now underway for the Market and Octavia, Balboa Park, and the Central Waterfront neighborhoods. When completed, these plans will serve as blueprints to help guide the evolution of the neighborhoods over time—ideally in ways that will enhance neighborhood identity, promote well-designed housing, parks, and community services, and nurture a cosmopolitan quality of life.

The Planning Department is working with residents and citywide stakeholders to identify appropriate planning actions—both preservation of existing desirable features and selective additions to the environment. It’s an opportunity to address both the citywide need for new parks, for preservation of beloved resources, for insertion of badly needed housing, for job creation, and for the addition of services—Muni, utilities, fire, police, and schools, to name a few. The goal is to achieve a consensus that residents, public officials, and developers all understand and abide by. These plans will then enable the City to set funding priorities and schedules for neighborhood improvements.

Although this neighborhood planning will take time, ultimately these plans will save both time and money for the City, community activists, and housing developers. The reason is that the Planning Department received enough funding to conduct full environmental reviews on the plans once they are completed. Any project that falls within the parameters of the plan will not have to go through duplicative environmental review. Projected impacts can be dealt with up front with specific mitigation measures (transit, open space, etc.).

This process has actually been done twice before in San Francisco, for the Rincon Point/South Beach Plan and for the Van Ness Corridor Plan. Significantly, these are precisely the two areas where a large portion of the City’s new housing has been built in the last decade.

The neighborhood planning process represents a chance for the city to move beyond the defensive inertia that too often prevents us from improving our neighborhoods. It provides us with the chance to ask, How can we improve our city and neighborhood over time? How can we improve walkability, livability, urban design, streetscape—or whatever it is that is most pressing?

Our hope is that it will enable new housing to be created with less uncertainty and stress—and lower costs—for everyone involved. When developers look at potential sites for housing, they will know what the community wants. The community knows up front that their concerns are being addressed comprehensively, and city officials may be able to support housing without risking the wrath of public opinion. If the plans are done right, this process will become an ongoing staple of planning practice in San Francisco, a way to balance citywide needs with neighborhood-specific needs and to plan thoughtfully for better neighborhoods over time.