Contracting is a critical part of local government service delivery. Each year, San Francisco enters into hundreds of new contracts for social and health services, architecture, design, construction, goods, and other services. Contractors include individuals, small and large companies, and non-profit organizations. In 2002, the Civil Grand Jury estimated that there were in excess of $1 billion in City contracts for professional services alone, with an average duration of two to four years.1 That figure is only a portion of the total—it does not include construction contracts or contracts to purchase goods and supplies. In the social-service arena alone, San Francisco contracts with 664 different non-profits for over $611 million to provide housing, food, shelters for the homeless, substance abuse prevention, mental health counseling, child-care, services to the elderly, and other services.2

Clearly, given this large financial scale, our ability to contract effectively has an impact on the City’s ability to deliver services to residents.

Because of the central role of contracting in the delivery of public services, the City should have an efficient, fair, straightforward, and transparent process for awarding and administering these contracts. In addition, the public interest requires that the City provide the broadest opportunity possible to private and non-profit sector organizations to compete for a portion of these funds.

But San Francisco’s contracting process is in many cases unnecessarily slow and burdensome for both the City and potential vendors. The process of awarding and administering new contracts is often time-consuming, inefficient, confusing, and unpredictable.

While many of the regulations affecting the contracting process have the commendable goal of preventing fraud and corruption in government, they unnecessarily limit the City’s ability to function effectively. In many cases, the goal of preserving a system free of favoritism and corruption can be maintained and strengthened, while also improving government service delivery and reducing cost.

The contracting process scares away many qualified firms. San Francisco says it wants to increase opportunities for women and minority-owned businesses to benefit from City contracts. But some of the contractors the City’s system is designed to help are the very firms most hurt by the burdensome nature of the process. Many minority-and women-owned firms remain economically disadvantaged, and many lack the technical, financial, or legal resources required to navigate the City process. The burdensome nature of San Francisco’s contracting processes has the effect of undermining the City’s explicit goal of remedying these inequities.

Much of the literature on City government contracting focuses on the question of which services should and should not be contracted out. This is not the focus of our paper. In SPUR’s view, much improvement can be made without wholesale changes to the City’s policies on these issues. We focus in this report not on whether and to what extent services should be contracted, but rather on how to improve the contracting process when the City decides work should be contracted.

Our point in this regard is simple: whatever the criteria for deciding whether or not work should be contracted or whether or how social policies should be pursued, the decision should not be based on the administrative inconvenience of the contracting processes.

In this paper, we assess the changes necessary to improve the contracting process. We ask the question: How can San Francisco ensure it minimizes waste and inefficiency, get the most for every dollar of taxpayer money it spends when it contracts, while maintaining strong safeguards against favoritism and corruption?

Many of the suggested changes here are not revolutionary or new ideas, but rather common-sense changes. SPUR believes the key to achieving these goals lies in changing the role of the Office of Contract Administration (OCA), making it the central point for administration and rule-making for the City’s contracting process. At the same time, City departments must be allowed the flexibility to use contracts to provide public services in the most effective manner, while being held accountable for complying with City rules and policies. Some of the recommendations in this report can be accomplished administratively, without legislation approved by the Board of Supervisors or voters. However, many of the core recommendations, in order to be effective, will require a change in the City Charter that redefines the role of the OCA and other agencies.

Problems With the Current Process

The process of developing, advertising, bidding, negotiating, and approving a contract is long and complex (see summary flowchart).

The specific processes vary somewhat depending on the type of contract, but there is no question that the delays and administrative clumsiness of the contracting process have real costs for City government. Because delays and complexity translate into financial costs to contractors, they are passed on to the City in the form of higher bids and negotiated prices. One local construction cost estimator estimates that there is a cost premium of 6 to 20 percent in working with the City over the private sector.

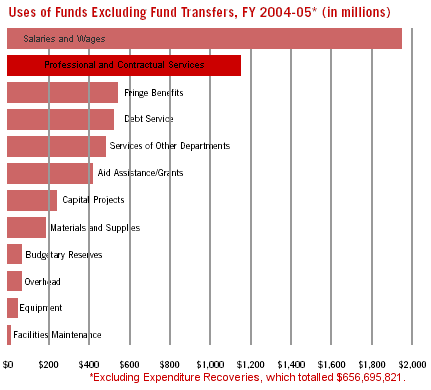

San Francisco does not have an easily accessible account of the total number and value of contracts it lets each year, partly because of the decentralized nature of its contracting processes and partly because of the fact that the City still uses a paper-based system for many contracts. According to the Controller’s Office, encumbrances posted (the funds that are formally committed to pay for a specific good or service) provide a proxy for the total dollar value of contracts. In FY 2003–04, the City posted encumbrance of $1.24 billion for goods and services—approximately a quarter of the total annual budget. This is roughly in line with one study suggesting that on average local governments spend 25 to 40 percent of their budgets on goods and services.3 Given the huge amount of money involved in contracting and the evidence on the administrative costs of public contracting, it is clear that even modest improvements to the process could lead to huge savings in administrative costs alone—not to mention savings resulting from a more speedy and efficient engagement in the market for goods and services.

Fig. 1: CONTRACTS FOR SERVICES AS A PORTION OF THE CITY BUDGET

Delays in contracting have other costs as well. For construction projects, for example, total costs can increase dramatically as a result of delays in contracting for architecture, design, or engineering services. With construction costs rising faster than inflation, time delays can increase costs dramatically, much like the Bay Bridge cost overruns resulting from slow decision-making processes. Over the past 25 years, construction costs have increased at an average of 3.5 percent per year, but in recent years have risen much faster as escalation of material prices has dramatically outpaced inflation.4 A six-month delay in contracting with an engineering firm for a project can significantly increase the amount the City must pay to build any given structure. Thus, numerous small delays can have massive costs for the City overall, especially during times when, like recent years, construction costs have risen faster than overall inflation.

The problems with the City’s contracting process are generally well known to those in City government, and those who have considered bidding on City contracts. Specifically, some of these problems include:

- Too many points of authority. There are multiple agencies that must review or approve any given contract. Even purely administrative functions are divided up among multiple agencies, creating a paper chase. Between the time a department first begins to develop the scope of work for a contract and the time funds are authorized to pay the contractor and work begins, the following agencies will all likely have some role in the process: the City department issuing the contract, the Commission overseeing the department issuing the contract (for example, the Recreation and Park Commission if the Contract is issued by the Recreation & Park Department), Human Resources Department, Civil Service Commission, City Attorney (in many cases, this includes multiple attorneys representing different agencies in the process), Human Rights Commission, Controller’s Office, Mayor’s Office, and the Office of Contract Administration. In addition, some contracts must be approved by the Board of Supervisors and are subject to review by the Board of Supervisors Budget Analyst.

- Slow payment. In many cases the City takes a long time to pay vendors. This can create huge problems for small businesses and non-profits with cash flow constraints, leading to reservations about working with the City.

- Inconsistencies between departments. Potential contractors have vastly different experiences working with different departments and have a new learning curve should they bid with a new department. Similarly, vendors working with different departments are asked repeatedly to submit the same information in different formats to different departments. This process is time-consuming and frustrating for vendors, who might reasonably expect different agencies within City government to be able to share the information. The OCA has provided model (i.e. not required) forms for many documents, but inconsistencies remain in practice.

- Too much oversight, minimal support. Departments that are highly experienced and successful at contracting are often burdened by having too many requirements from too many different authorities at each step of the process. At the same time, departments with little experience and capacity for contracting often do not know where to get the professional support they need to manage the process effectively.

- Lack of performance standards and guidelines. Departments do not have a source of benchmarks or performance goals to help them evaluate their own performance in contracting.

- Lack of communication between departments. City departments often fail to share the successful practices they have developed, leading to inconsistencies in the way they interact with bidders and businesses interested in working with the City. Again, this leads to confusion among vendors and a perception that the City is disorganized and unpredictable.

- Lack of outreach, information and access for potential vendors. Despite the best efforts of many departments, the City could do a better job of outreach and of providing clear, easily accessible information to potential contractors about opportunities to work with the City and how to take advantage of them.

Primary Concepts for Reform

As with many questions of administrative efficiency, discussions of contracting and procurement functions are often framed in terms of whether centralization or decentralization is more appropriate. Does a city achieve economies of scale and greater consistency by consolidating contract functions in a central office? Or does decentralizing control of these functions to individual departments allow them to better accommodate their own needs and develop systems appropriate to their particular circumstances?

The question of centralization versus decentralization is, in a sense, based on a false dichotomy. Broadly speaking, San Francisco should centralize some aspects of contract administration and rule-making, while at the same time decentralizing decision-making on individual contracts in certain cases. Centralization and consolidation is appropriate where there is an interest in citywide uniformity in behavior between departments, and when there are time and cost efficiencies associated with doing tasks of the same nature in a single place. Decentralization is appropriate for activities that require discretion and judgment based on particular contract or program facing a department.

Many of the specific recommendations here follow two organizing principles:

- Centralize and strengthen administrative functions in the Office of Contract Administration. OCA should become the focal point in City government for ensuring that contracting is administered efficiently citywide. As discussed above, the administrative functions are currently fragmented and dispersed across multiple agencies. OCA would take on the role of a central facilitator for departments’ contracting efforts, in contrast to the often fragmented, obstructionist role of the many different points of authority in the current process. Some of these responsibilities would require a more independent OCA, separated organizationally from the purchaser where it is now located.

- Decentralize authority over implementation and decisionmaking for departments with demonstrated capacity to carry out these functions effectively and in compliance with City policies. Some City departments have the capacity effectively to carry out contracting processes without a large amount of guidance and oversight while conforming to City standards. For these departments, it is inefficient to require centralized scrutiny and burdensome requirements at each step of the way for every contract. Instead, the City should move to a model where these departments are often allowed to structure, bid, negotiate, and sign their own contracts with little involvement from other authorities, so long as they are shown through a monitoring process to do so effectively and fairly. Instead of monitoring every action at every step of the process, oversight of these departments should be altered to focus on the results of their actions at the end of the day.

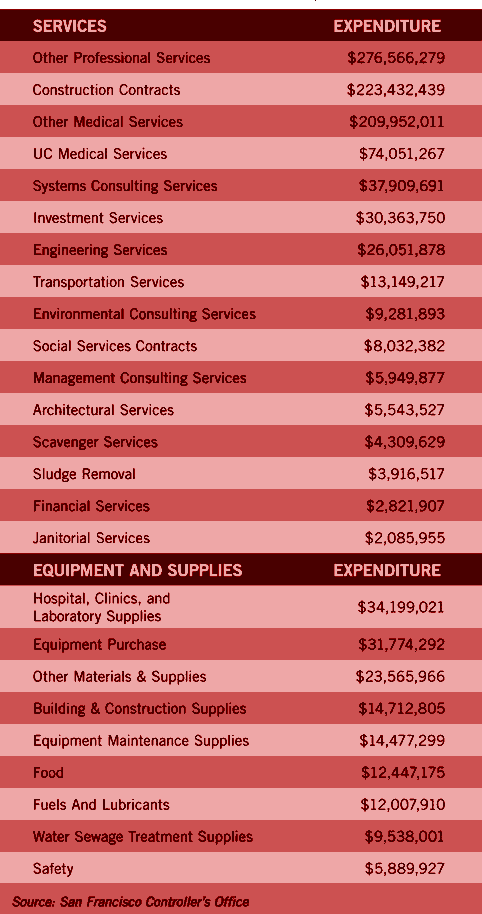

Fig. 2: CONTRACT-RELATED SPENDING BY CITY GOVERNMENT: SELECTED CATEGORIES OF ENCUMBRANCES POSTED, FY 2003-04

While data on the number and dollar value of contracts entered into by City government are relatively inaccessible, the information in this table helps provide a general sense of how the City's contract-related expenses are distributed. The table includes selected "encumbered" funds for goods and services in FY 2003-04, meaning funds that are set aside for expenses the City has committed to paying. Thus, while the data are not quite an accurate representation of how many dollars are spent through contracts of a given type, it provides an approximation. The large "Other Professional Services" category includes many encumbrances related to the other service categories—such as architecture and social services—that are placed in the “other” category for accounting purposes. San Francisco posted encumbrances totalling $701,940,097 for services and $158,612,395 for equipment and supplies during the year.

Recommendations

1. Consolidate Administrative Elements of Social Policies in a Single Agency

Many of the tasks associated with the day-to-day administration of the City’s Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) program (formerly the Minority and Women-owned Business Enterprise [M/WBE] program, and likely soon to be replaced by a program favoring small local businesses) reside within the Human Rights Commission (HRC). Many of these are fundamentally factual, non-discretionary administrative tasks, and are not related to the HRC’s core advocacy and policymaking role. These functions include:

- Certifying businesses as qualified for bid discounts. This involves processing applications and ensuring that businesses have local offices and gross revenues below the statutorily defined minimums. Currently this process involves certifying businesses under the temporary DBE program, which may soon be replaced by other permanent legislation.

- Bid Evaluation. The HRC is involved in evaluating contractor bids and Requests For Qualifications (RFQs) and Requests for Proposals (RFP) to select vendors. The HRC applies the preferences to DBE bids as directed by the DBE section of the Administrative Code.

- Review and approval of Contractor Selection. The HRC reviews the process and outcomes of the contractor selection process, and has the authority to impede or nullify the decision to select a vendor made by a department.

- Compliance monitoring after an award has been made. The HRC is involved in oversight of contractors as they carry out projects to ensure compliance with City policies.

- Compliance with the Equal Benefits Rules established by the Board of Supervisors and HRC.

In 2000, in response to scandals over ethical abuses of the M/WBE program in City contracts, Mayor Willie Brown formed the San Francisco Independent Task Force on Affirmative Action in Public Contracting. The task force was composed of three individuals with backgrounds in civil rights issues. Its purpose was to make recommendations that would restore public confidence that the program was being operated ethically.

The task force hired staff, conducted dozens of in-depth interviews, and held numerous public hearings over the course of ten months. The task force’s core recommendation was that the City should move many of the non-discretionary administrative functions listed here into the Controller’s Office, on the grounds that they are essentially technical in nature, and better suited to an administrative agency than an advocacy-oriented one such as the HRC. In addition, the task force argued that removing these functions from the HRC would free up the HRC’s resources to focus on advocacy, outreach, and policy. However, its core recommendation of removing the M/WBE certification, bid analysis, award recommendation, and post-award contract compliance functions from the HRC and into a different agency was never implemented.

SPUR believes this core recommendation has merit, despite the fact that many of the circumstances under which it was developed have been resolved. However, we believe administrative functions should be centralized in the OCA rather than the Controller’s Office. Although the Controller’s Office has the strengths of political independence and administrative capacity, it is also responsible for a number of audit functions, and would be additionally responsible for the contracting post-audit activity recommended elsewhere in this report. The audit responsibilities create a conflict of interest by also handling the administrative tasks that would ultimately be audited activities. One problem with OCA as a location for these functions is that it is organizationally tied to the Purchasing Department, which enters into hundreds of contracts per year. This creates a potential conflict of interest in that OCA would be responsible for administrative oversight of its own contracts. To provide OCA with the neutrality necessary for this function, it would need to be separated organizationally from Purchasing and made more independent.

As discussed elsewhere in this report, advocacy and outreach will play an increasingly important role in the post-M/WBE context. Shifting contract administration functions out of the HRC and consolidating them an administrative agency would free up resources for the HRC to engage in these core functions. These functions include expanded outreach efforts, identification of barriers to women and minority-owned firms in winning government contracts and carrying out the work, development of policy to help those businesses become engaged with public contracting opportunities, and ensure the City is implementing policies designed to engage small local businesses and address discrimination in contracting.

2. Improve outreach, information, and access for potential contractors

In order to increase competition for City contracts and ensure equal opportunities for potential vendors to bid on City contracts, it is necessary that the City do a better job of communicating with potential vendors, making information on upcoming contracts accessible, and improving awareness of the City’s contracting process.

The City has full control over its own demand for the goods and services it wishes to purchase from contractors. However, the private market will not necessarily take care of the supply side of the equation on its own. In order to stimulate competition from bidders, thereby maximizing quality and minimizing price, the City must engage potential suppliers.

Currently, the City makes some efforts to engage prospective vendors. The Human Rights Commission conducts some outreach and training for potential vendors. In addition, OCA has developed an online database of contract opportunities and taken major steps in increasing online accessibility of documents. This effort should be encouraged and expanded so that every City contract opportunity is centrally posted and easily accessible to potential vendors.

Further investment in outreach and information distribution to prospective vendors will increase the supply of goods and services available to the City, decreasing costs, increasing the quality and quantity of goods and services available, and maximizing involvement by a cross-section of vendors. The HRC is well positioned to take a leadership role in outreach to small and disadvantaged businesses if funding is made available to do so. Improving outreach and accessibility should be a primary function of the HRC with respect to contracting.

3. For Small Contracts, Use a Post-Audit Approach to Test Compliance by Departments with City Policies

A primary source of the inefficiency in San Francisco’s contracting process is that it is set up to scrutinize each contract at each step of the process. Contracts must be approved by multiple authorities, with additional scrutiny and oversight as the contracted work is being carried out. These layers of scrutiny were developed with the best intentions and many should remain in place. However, the administrative inefficiencies they have collectively created offset the benefits they were intended to achieve.

It is impossible for the City to effectively monitor every action taken on every contract. Instead, it should move toward a “post-audit” approach for City contracting. This would mean that instead of requiring review at each step as a contract moves forward, a sample of contracts would be audited by the Controller’s Office after the fact, and those sample audits would be used to hold departments accountable for their overall contracting performance.

The post-audit approach creates a strong incentive for departments to comply with City policies. At the same time, the City achieves the administrative benefit of only being required to scrutinize a portion of contracts, instead of all of them.

The post-audit approach has been used successfully by the City to monitor other types of transactions, most notably financial processes. By definition, a post-audit approach will not catch every problem with City contracts. However, the cost of enforcing compliance must be weighed against the desired results. With improved use of information technology, the post-audit approach becomes easier to administer and provides more information about performance.

That said, post-audit is not a universal solution to the City’s contracting problems. In order for the post-audit method to work, it must be applied to more or less repetitive transactions, so that the audited transactions are generally representative of the others, and any problems it uncovers can be addressed in similar transactions in the future. For example, the approach would not be successful if applied to a massive engineering contract for the City’s Hetch Hetchy Water system renovation. If a problem with such a contract were discovered after the fact, it would be too late to correct the problem, and it could not be remedied in future transactions since projects of that scope occur only once every several decades. Thus, it would be appropriate to use post-audit for contracts below a certain dollar threshold. Moreover, if sufficient data are not available for auditors to accurately measure performance in an audited contract, the approach cannot be successful. This means a post-audit approach should only be applied after effective data-gathering processes are in place. The Controller and OCA should work to develop guidelines for when post-audit can be effectively used on smaller, more repetitive contracts, and when it is inappropriate.

Finally, there must be a response if a Department is shown to have acted inappropriately in its contracting processes. Departments should receive feedback about the results of the audits of their contracts, including whether any “red flags” show up that may indicate performance problems. If problems persist, as measured against pre-established guidelines, the department would lose some degree of control over its contracting processes, as well as control over its budget for contract administration. In other words, the department should revert to a higher level of scrutiny in its contracting, coupled with additional training and support to strengthen its processes until it demonstrates that it is once again capable of returning to a lower level of oversight.

4. For smaller contracts, measure achievement of Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) and other social goals on an aggregate annual basis for each department rather than in individual contracts.

Currently, the contracting department and the HRC determine set-aside levels for each individual contract based on the type of work and availability of disadvantaged businesses in the industry that will perform the work. The City’s set-aside levels for disadvantaged business preferences can be achieved at the same levels, but with greater efficiency, by allowing the departments greater flexibility about how much of each contract to set aside for DBEs and holding them accountable for meeting a predetermined goal for aggregate dollar values of contracts given to DBEs over a given period of time.

Under the proposed system, departments would work with the HRC to develop annual goals for the dollar value of contract work that would go to DBEs over a given year. Departments would then be responsible for developing levels of participation on individual contracts. At the end of the year, the HRC and OCA would examine the department’s record to determine whether it had in fact met the predetermined goals. If a department met or exceeded its goal, it would repeat the process the following year. If it did not, it would enter into a “probationary” period, where the OCA and HRC would renew their involvement in individual contract goal setting, and work with the department to identify processes to allocate a more appropriate share of contracts to DBEs.

The advantage of such a system is that the departments, who have the best understanding of the work being contracted out, will have greater flexibility to select the appropriate vendors based on the specific circumstances of the project and their knowledge of upcoming contracts. This flexibility will allow the departments to allocate work to DBEs in the most efficient manner, based on contractor availability, price, and market conditions. For example, if a department is seeking design services for a building project and a large number of qualified DBEs are available to work on the project, it could choose to exceed the current normal levels of DBE participation. If on a subsequent project few DBEs expressed interest or were available to bid, the department could award a higher portion of the contract to non-DBEs, rather than struggling against the grain of the market and paying higher prices to meet DBE goals or create an incentive to develop “phony” DBE relationships with the prime vendor. In the aggregate, the department would award the same total number of dollars to DBEs—but it would do so at a time it determined most appropriate. Because the fundamental purpose of the DBE program is to provide opportunities and build capacity in disadvantaged businesses, there is a danger that a program of this nature would result in departments achieving their goals through a smaller number of large contracts with their favorite DBEs, reducing the total number of businesses who benefit from the program. It may therefore be appropriate to also set additional goals for the number of opportunities provided, instead of simple dollar values.

5. Use Electronic Tracking and Processing of Contracts

San Francisco still uses a paper-based system for review and approval of most contracts. Shifting to a centralized database for contract information will substantially reduce the time needed for approval, allow the City to collect better data about its processes, and improve accountability among the various actors involved in the process. Strange as it may sound, many City contracts still physically travel from agency to agency for approval.

An electronic system would help provide data on the City’s process and the sources of problems. Since time delays are a central factor in increasing the cost the City must pay for goods and services, it is highly desirable to have access to data on the length of time associated with various parts of the City’s internal processes.

The city should invest in a centralized database, administered by the OCA and accessible to various agencies and the public online. Other cities have implemented similar systems to impressive effect. Philadelphia, for example, has used a centralized tracking and electronic review of contracts for over a decade. The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission has begun to implement such a system to improve processing of contracts for the Hetch Hetchy water system renovation program. The contracting system being developed for the upgrade is innovative and shows great promise for substantially improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the program. The OCA should research and implement a similar citywide system. Documents would be posted online, and notices sent to City staff informing them of a contract’s status as it moves through the process and notifying them when it is time for them to act on a contract. The advantages of such a system are several:

- Access to information on the contracts would improve for departments, vendors, and the public.

- The time for various reviews and approvals would be reduced by allowing simultaneous review of documents and eliminating the need for the contracts to physically travel around the City.

- Better data would become available on the length of time required at each stage in the process, allowing the City to better identify the points of inefficiency and likely future problems in the process.

- Accountability among agency representatives would be improved. Since better data would be collected, agency staff would become conscious that the length of time and likelihood of problems involved in their phase of processing, increasing the sense of accountability for performance.

- Better and more timely review of achievement of DBE goals and other social policy goals would take place.

- Faster payments would be made to vendors, since better information would be available, reducing the number of potential complications that can prevent invoices from being forwarded to the Controller for payment and identifying the causes of delays.

- Greater transparency and easier public access to information about the City’s contracting decisions would be the norm.

6. Impose Strict Timelines for Approval by Various Agencies

As discussed elsewhere in this report, the timelines for approval of contract documents by the various agencies are often open ended. Taking the simple step of imposing formal review timelines could shorten these timelines and improve accountability among these agencies. If these timelines are not met, OCA and other agencies can intervene to determine whether there is a problem with approval processes.

7. Allow Simultaneous Review by City Agencies

Currently, once a contract is negotiated between a Department and a vendor, it must be reviewed by a number of agencies, including the department issuing the contract, the City Attorney’s Office, and finally the OCA. In many cases these reviews do not have to occur sequentially, but could happen simultaneously or at least on overlapping timelines. In its new capacity, OCA should help move contracts through the various approval stages on the shortest timeline feasible. This will lower the length of time needed to get a contract approved and help identify any problems earlier in the process.

8. Develop and Enforce Departmental Performance Measures for the Length of Time Required to Pay Vendors.

One commonly cited problem among small businesses and non-profits contracting with the City is delays in payments. Late payments can be very difficult for businesses that must use debt to pay for their expenses while working with the City, and for non-profits operating on tight budgets. Uncertainty about being paid on time can cause these organizations to be hesitant to work with the City, reducing the pool of prospective vendors, and can lead vendors to build a premium into the price they charge the City in order to account for the uncertainty. The reality that payment delays are commonplace when working with the City is a very serious problem. Specifically, payment delays present the strongest deterrent to working with the City to the small, disadvantaged organizations the City is actively seeking to engage. The payment delay problem is one of the most obvious ways in which the City’s administrative shortcomings have the unintended effect of undermining its explicit policy goal of engaging small and disadvantaged businesses.

While the Controller’s Office has a prompt payment policy, it cannot begin processing payment until it receives the proper documentation. Many of the problems with payments to vendors are a result of delayed processing of invoices at the department level, or a lack of clarity and communication regarding the information vendors must submit to the City to receive timely payment. Moreover, many subcontractors complain of delays in payments from prime contractors. These problems may be reduced to a degree by simply adopting more modern tracking and monitoring systems, as discussed elsewhere in this paper. However, the City would also benefit from centrally developed, clear performance goals and measures for timeliness of payment, with the results made accessible to the public and potential vendors. Tracking and publicizing payment timing would help identify problems when they exist, and provide confidence to potential vendors considering working with those departments where effective payment systems are already in place.

9. Use “As-Needed” Contracts to Reduce Delays

Many jurisdictions, including the federal government, State of California, and numerous cities and counties (including San Francisco to a limited degree) sign “as-needed” contracts with vendors, which allow public agencies to purchase goods and services at a previously agreed-upon price without going through the entire contracting process each time the vendor’s services are required. The central purchasing agency reviews paperwork and documents submitted by the vendor, and negotiates a contract with a vendor specifying price and terms of service. Then, departments are able to use that vendor to purchase the goods or services at a previously agreed-upon rate, without repeating the contract process each time.

The clear advantage of this process is that it would allow departments to purchase work or services without repeatedly going through the cumbersome process of bidding and negotiating contracts. At the same time, the City will have done the legwork to make sure it is receiving services at a competitive price and quality level. Imposing a limit on the total dollar value of work that can be awarded to any single vendor on an as-needed basis, and requiring use of the normal contracting process for larger jobs, could temper concerns about abuse of such a system.

Some San Francisco agencies already use as-needed contracts on a limited basis, including the Department of Parking and Traffic, Planning Department, and Redevelopment Agency. As-needed contracts are most effective in cases where a well-defined service is used repeatedly. These contracts are most often used to purchase equipment and goods, but are increasingly being used to purchase some services. Because it is impossible to accurately anticipate the needs and costs of many of the larger, more complex projects the City must contract out, this approach is infeasible in many circumstances. However, it could have clear advantages for services that are relatively standardized and simple.

10. Further Professionalize Contract Administration

- Hold regular meetings of contracting professionals from all City agencies

One of the effects of the City’s current decentralized approach to contracting is that each agency operates in its own “silo,” developing its own practices and procedures. Taking the simple step of holding regular meetings of contracting professionals can help departments share effective practices, develop coordinated responses to policy changes, and facilitate more-effective allocation of City staff and financial resources.

Some departments are more effective at developing RFPs and RFQs, soliciting bids, and negotiating contract terms than others. The sharing of effective techniques and procedures will benefit all departments, so each one does not need to “reinvent the wheel” by developing its own processes. In addition, there may be economies of scale available to the City by coordinating contract scopes and timing to avoid repetition and redundancies.

In the past, DPW and the HRC held regular meetings of this nature, but over the past years the practice has fallen by the wayside. It should be reinstated and led by the reconstituted OCA. - Increase use of trained contracting professionals at OCA and other departments

Departments should increase the use of trained contracting professionals to help move projects through bid, award, and monitoring stages. These professionals would help navigate the various City processes, facilitate dispute resolution between agencies, and help departments and contractors comply with City policies.

Contract professionals could be either located full time in larger departments with high contract workloads, or provided by OCA to smaller departments that do not have a regular need for contracting expertise. OCA should help provide training for these professionals. - Provide training for City employees on the City’s contracting process

Many City employees have expertise in the industry or program area in which they work, but find the City’s contracting processes as confusing and intimidating as the potential contractors whose services they are engaging. Departments that contract regularly may have a high level of expertise on staff, but smaller departments and those that are beginning to implement bond or other major capital programs may require additional training. OCA should be given the resources to make this training available. Devoting resources to this training could result in substantial long-term savings to the City by reducing the costs associated with the contracting process.

11. Simplify the City’s Standard Contract Language

San Francisco’s boilerplate contract language is longer and more complex than most other jurisdictions. The length and complexity of the contract can be daunting to many potential vendors, especially small firms that do not have the resources to pay large legal fees to protect themselves against unexpected risk.

It is not feasible for the City to cover every potential circumstance in its contracts. Much of the language in this 26-page contract is for the purpose of reducing the risk faced by the City and articulating its social policies. Some of this language is, of course, necessary. However, the City Attorney’s Office and OCA should work to reduce the length and complexity of the contract based on examples set by other cities.

12. Develop Clear and Explicit Procedures for Fast-Tracking Contracts When Necessary

For some time-sensitive projects, the delays involved in the City’s contracting process create pressure to begin work before a contract is approved. This is a lose-lose situation for both parties. Contractors expose themselves to risk by committing time and financial resources without assurance that funding will be approved, and the City opens the door to problems with contractors who begin work, only later to find out that a contract will not be approved. In these situations, it is desirable to have a process for expediting processing of the contracts. The OCA should develop clear and explicit criteria for determining which contracts qualify for this “fast-tracking” and a process for expediting review and approval of those contracts.

13. For Major Capital Programs Requiring Multiple Individual Contracts, Allow Early Bulk approvals by the Mayor’s Office and Civil Service Commission

For major bond or other capital programs, it may be possible for departments to anticipate the scope and timing of a number of contracts in advance. In such cases, when contract needs can be projected, departments should be allowed to seek early authorization to contract out multiple projects, instead of obtaining authorization for each individual contract when the RFP is ready to be developed.

For example, in 2001 voters authorized revenue bonds to fund the PUC’s water system renovation program, which will include dozens of contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The Civil Service Commission and the Mayor’s Office must approve each of these contracts, a process that can take a month or more. Instead of beginning this review process when the PUC is getting ready to issue an RFP, which could result in time delays if the review process takes longer than expected, the PUC hopes to submit a large number of contracts for early review. This way, the review process will be completed well before the PUC is ready to issue its RFPs and begin the bidding process, and the PUC can go ahead when the time is ripe, avoiding the possibility of unnecessary delays with approvals.

Of course, because RFPs often change in scope as they are developed, this would require a safeguard to ensure that substantive changes trigger additional commission review.

endnotes

1 San Francisco Civil Grand Jury, 2001-2002, Professional Services Contracting.

2 San Francisco Board of Supervisors, Media advisory on non-profit agency audits, September 14, 2004.

3 National Association of State Purchasing Officials, Buying Smart: State Procurement Reform Saves Millions, www.naspo.org.

3 McCue, Clifford, Kirk Buffington, and Aaron Howell, The Fraud/Red Tape Dilemma in Public Procurement: A Study of U.S. State and Local Governments. National Institute of Governmental Purchasing, 2003, www.nigp.org.

4 Engineering News-Record, Construction Cost Index, enr.construction.com.