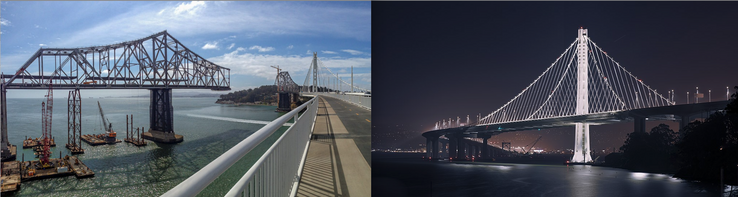

Credits: (left) CC0 licensed photo by Patrick Boehner from the WordPress Photo Directory; (right) Dllu, CC BY-SA 4.0

October 17, 2024, marks the 35th anniversary of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, which killed 63 people, injured more than 3,500, displaced more than 12,000, and caused an estimated $6 billion to $10 billion in damages. The magnitude 6.9 earthquake was the largest earthquake to hit the region since the magnitude 7.9 San Francisco earthquake in 1906. It exposed significant vulnerabilities in the region’s infrastructure, emergency services, telecommunications, and housing stock. The quake destroyed the I-880 freeway viaduct in Oakland, dropped a span of the Bay Bridge — closing it for a month — collapsed historic buildings in Santa Cruz and apartment buildings in San Francisco's Marina District, and dramatically transformed the San Francisco waterfront.

The removal of the quake-damaged Embarcadero Freeway in 1991 reconnected the city with its waterfront, giving visibility to the Ferry Building and shifting the focus of residents and urban planners from private vehicles to public space and public transportation. Construction of key landmarks along the Embarcadero such as AT&T Park (now Oracle Park), South Beach Marina, and the Exploratorium helped revitalize the area, which had struggled in isolation from the city. In 1992, the Central Freeway, another elevated freeway damaged by the quake, was closed and later replaced with Octavia Boulevard, a more pedestrian-friendly road lined with trees, new housing developments, and Patricia’s Green.

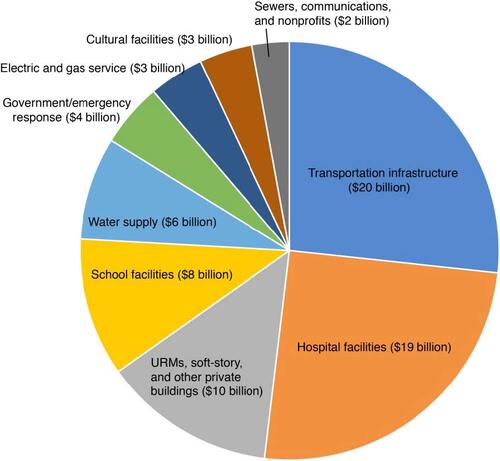

Since the Loma Prieta quake, about $80 billion has been invested in preparing the Bay Area for the next major seismic event. Efforts include retrofitting or replacing transit infrastructure, hospitals, housing, schools, and utilities and improving communication systems and emergency response capacity.

Seismic improvements and replacements in the Bay Area represent a $74 billion investment.

San Francisco alone has invested more than $20 billion since Loma Prieta to increase the city’s resilience. Other local jurisdictions, regional agencies and service providers, and the State of California have implemented a multitude of policies and projects to protect residents from future earthquakes. On this anniversary, the Bay Area can celebrate tremendous progress as well as acknowledge how much more needs to be done.

Progress

Statewide Action: Transportation System Upgrades

Given significant damage to highways and bridges after Loma Prieta, the state began a bridge evaluation and retrofit program that has strengthened more than 2,200 major state-owned bridges located along state highway systems, including the Bay Bridge. The Bay Bridge is one of the Bay Area's most vital transit routes. Its new eastern span, which replaced the original structure from 1936, was completed in 2013 and cost $6.4 billion. The bridge was designed not only to withstand major seismic events but also to remain operational immediately after an earthquake. This work ensures that transportation across the Bay will continue during critical recovery efforts. BART has also completed evaluations and upgrades across its entire system, including the $1.2 billion seismic retrofit of the 3.6-mile Transbay Tube, a project funded by Measure AA, approved by the region’s voters in 2004, which issued $980 million in general obligation bonds.

Statewide Action: Early Warning Alerts

Early warning systems provide critical seconds of advance notice before shaking begins. The rollout of the California Earthquake Early Warning system managed by U.S. Geological Survey ShakeAlert could make a life-saving difference by allowing people to brace for shaking and automated systems, such as transportation and utilities, to take immediate protective actions.

Municipal Action: Building Retrofits and Response Coordination

In 1986, before Loma Prieta, the state mandated that jurisdictions with a high seismic risk inventory develop loss reduction programs for unreinforced masonry (URM) buildings — generally brick buildings that lack reinforcing material like rebar and therefore collapse outward during intense earthquake shaking, endangering people on the street. In 1992, San Francisco adopted a URM ordinance that required owners of URM buildings to assess risk and retrofit their buildings. Under this program, more than 2,000 at-risk URM buildings have been seismically upgraded.

In 2013, San Francisco initiated another seismic retrofit program, this time requiring the city’s wood-frame soft-story buildings with five or more units to be retrofitted by owners. As of 2023, more than 4,000 soft-story buildings have been retrofitted, leaving the program with a greater than 90% compliance rate, according to city staff. The city is now working on a concrete building safety program to mitigate the collapse risk of “brittle” concrete buildings.

Other Bay Area cities have adopted local building retrofit mandates for seismic safety. Oakland, Berkeley, Albany, and Mill Valley have mandated retrofitting of wood-frame soft-story buildings. In September, the San José City Council also advanced a program for soft-story retrofits. The program will be implemented once the city receives hazard mitigation grant funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Buildings aren’t the only focus of seismic retrofits. In 2018, San Francisco voters approved a $425 million bond to begin fortifying the Embarcadero seawall’s most vulnerable sections, a critical project for improving San Francisco’s seismic and sea level rise resilience.

In addition to retrofit programs, San Francisco runs a new program, the Lifelines Council, dedicated to improving the preparedness and response capabilities of lifeline infrastructure, including drinking water, waste water, electricity and gas, communication, and transportation systems. The city launched the Lifelines Council in 2009, and the group meets quarterly to coordinate earthquake recovery efforts across utilities, transportation, and communications sectors. The Lifelines Council was established as a result of advocacy by SPUR and our partners, and it reflects a recommendation of SPUR’s Resilient City initiative.

Work to Be Done

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, in the next 30 years the Bay Area has a 51% chance of experiencing a magnitude 7.0 earthquake. Today, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake in the Bay Area is likely to result in 10 times the losses of the 1989 earthquake (about $80 billion in damages) due to continued growth and development in the region over the last 35 years. Although the region has made significant advances in addressing the seismic vulnerability of buildings and infrastructure, gaps remain in its preparedness. Ongoing investments in policy, infrastructure, and public education are crucial to ensuring the region's resilience against future seismic events.

Policy and Funding

More cities must advance retrofit programs and mandates for the at-risk housing stock in their jurisdictions. These buildings pose safety risks to occupants, and the loss of this housing in the event of an earthquake could lead to displacement of lower-income residents. The state can support this effort by funding the Multifamily Seismic Retrofit Program, which was funded by Governor Newsom in 2023, then cut this year due the state budget deficit. More federal funding, dispersed on reliable timelines and with greater flexibility by agencies like FEMA, is crucial to help local jurisdictions advance retrofit programs. The biggest hurdle to public approval of retrofitting is the financial burden it might place on mom-and-pop landlords and low-income renters.

Improved Building Codes

Improvements in the building code over the last 50 years mean newer buildings are much less likely than older buildings to collapse and kill occupants. Despite these improvements, some newer buildings may be rendered unusable in the aftermath of a quake. According to a SPUR report, some might not be occupiable for months due to broken water and gas pipes, and others might sustain structural or other damage that is too expensive to repair. There is a growing push to enhance design and building codes to include requirements for "functional recovery.” Accordingly, buildings and infrastructure such as roads and bridges would be designed to be operational soon after a quake — speeding recovery by keeping people in homes and critical services functioning.

The National Institute of Standards & Technology (NIST) is already working with experts to improve building codes for functional recovery, but it could be decades before these efforts turn into building code updates in California. Local jurisdictions can speed up this timeline by adopting resiliency or “functional recovery” building codes before guidance from NIST moves forward. For example, jurisdictions could require new housing developments as well as senior centers, homeless shelters, grocery stores, or other buildings with critical services or serving vulnerable populations to be built to higher standards — without significantly increasing construction costs. In 2018, Governor Newsom vetoed AB 1857, a bill that would have initiated the development of a functional recovery building code policy in California.

Public Education

As public memory of Loma Prieta fades, education remains a key aspect of preparedness. Instilling awareness of earthquake risks and safety measures in school-age children is essential. This awareness can be raised through science or history lessons on seismic risks and through school-wide earthquake drills. For example, October 17 is the Great California Shake Out, a day when millions of residents take part in earthquake drills at work, home, and school. Programs like this are critical in ensuring that earthquake awareness — and the commitment to investing in resilience — passes to future generations.