Many cities grappling with post-COVID-19 economic recovery have seized on the concept of the “15-minute city,” a city with “complete” and connected neighborhoods where people are able to meet most, if not all, of their needs within a short walk or bike ride from home.

In urban areas around the world, the tenets of the 15-minute city (or the 10-minute or 20-minute city in other locales) have been embedded in policies to create transit-oriented communities, develop public realm and greenspace enhancements, and implement traffic reduction methods. In the aftermath of the pandemic, more cities are looking to these tenets to support an equitable economic recovery in the form of resilient, healthy, and prosperous communities composed of mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods. In pursuit of more self-sufficient neighborhoods, cities are striving to regenerate urban centers, enhance social cohesion, improve health outcomes, and increase housing density.

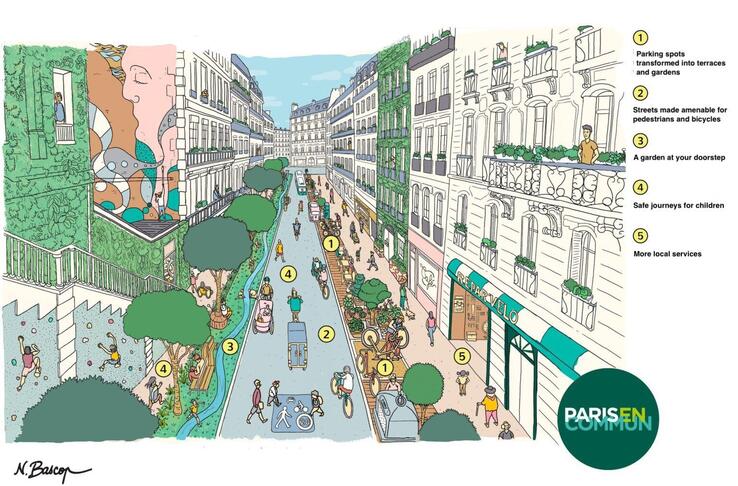

Paris Envisions 15-Minute Neighborhoods

Source: N. Bascón/Paris En Commun

For cities like San José with sprawling footprints and office-centric downtowns, these goals might sound lofty. Yet San José embraced very similar principles back in 2011, when it proposed “urban villages” as one of the pillars of Envision San José 2040, the city’s ambitious general plan. Urban villages were conceived as higher-density, mixed-use districts that could accommodate job and housing growth while reducing the impact of that growth by promoting transit use and walkability. Based on extensive community outreach, the plan proposed 60 urban villages across the city. But progress has been slow, and only 14 of the villages have been planned and approved. As San José plans the remaining 46 proposed villages, SPUR believes the city can find inspiration in the 15-minute city concept. Indeed, this concept could guide San José’s land use strategy, as well as development and implementation of policies and investments, to more effectively and equitably plan for connected and complete neighborhoods.

SPUR has assembled a cross-sector working group, conducted interviews, and consulted with stakeholders to better understand the utility of the 15-minute city concept for San José. How can the city’s planning system and policies — along with public-private collaborations — apply this framework to transform neighborhoods into places that support health and advance inclusive prosperity? This fall, we will publish a policy brief and a kit of tools that San José can use to apply 15-minute-city principles to equitably accommodating housing and commercial growth, improving access and mobility, and planning for amenity-rich neighborhoods. As a preview, this article explores the background of the 15-minute city concept and its relevance to San José.

Evolution of Neighborhood Planning Movements and Frameworks

The 15-minute city framework follows a century-plus city planning tradition based on walkable, mixed-use urban design principles for effectively accommodating urban growth, city services, and new patterns in mobility and access.

Beginning in the 1890s with the Garden City movement, planners started exploring the idea of self-contained communities surrounded by greenbelts. Their efforts were in response to the environmental degradation and health impacts of the industrial revolution. In the 1920s, Clarence Perry, in one of the first attempts to grapple with increases in automobile use and traffic, introduced the neighborhood unit as the basic planning unit. Perry envisioned neighborhoods wherein residents would be able to live near schools, parks, and commercial spaces — neighborhoods that discouraged driving.

But few listened. Around the same time, planners and architects began to create cities and neighborhoods that emphasized higher-density, high-rise buildings and that expanded parking spaces and highways to accommodate cars. In seeking to plan cities to be accessible via cars, modernist urbanism and design effectively began to separate living and work environments, while spreading out other services and amenities.

These design concepts and many others guided urban form toward decentralized living, work, and play environments for the better part of the 20th century. Eventually, the negative impacts to quality of life in the form of traffic, deepening inequality, and climate impacts led to new planning concepts. These concepts focused on bringing human-scale design to neighborhood and city planning.

In the 1990s, the Congress for New Urbanism began to posit cities with a range of housing types and mixed uses. Its benchmark was a five-minute walk among nodes of commercial activity. New Urbanism seeks to address the ills of urban sprawl and suburban development by building more walkable streets, housing, and shopping within close proximity. The approach emphasizes the value of accessible public spaces. The 15-minute city, which has emerged in the last decade, is an evolution of this idea.

From Garden City to 15-Minute City

Source: SPUR

15-Minute City Framework and Models

As envisioned by Professor Carlos Moreno, the 15-minute city has multiple centers and neighborhoods with mixed land uses. The concept’s key sustainability and equity components are proximity (to amenities), diversity (both mixed land uses and people/culture), density (people per square mile), and digitalization (the extent to which technology and data meet needs and provide services). The concept is meant to be adaptable to unique city characteristics and land use patterns while emphasizing human-scale urban design and multiple uses of public space. Some amenities, goods, and services identified as essential for social cohesion and walkable environments include grocery stores, schools, parks, medical clinics, offices, entertainment, and community spaces or centers.

The framework approaches urban planning as a way to leverage land use development, urban design, and placemaking strategies to build communities where all people can enjoy a high quality of life. To fulfill this promise, the framework includes provisions for service delivery that can effectively respond to socio-economic challenges and structural inequalities, and data collection that can set up investments to restructure cities for inclusive prosperity.

Carlos Moreno’s 15-Minute City Framework

| Key Components | Service Delivery | Data Collection | |

| Density | Allows for equitable delivery of economic, social, and environmental benefits | Opportunity to improve city service delivery to locals | Opportunity to leverage metrics, indicators, and other data to inform the equitable development of policies and deployment of investments

|

| Proximity | Allows residents to enjoy provision of essential services in commercial and public places | ||

| Diversity | Promotes inclusivity and communal uses of resources | ||

| Digitalization | Allows for innovative service delivery and human-scale urban design | ||

The framework is adaptable to individual city contexts and features human-scale urban design iteratively informed by services provision and data collection.

SPUR has identified three cities that are using the concept of the 15- (or 10- or 20-) minute city to inform their vision of complete neighborhoods and to embed that vision in their municipal policy:

Paris, France

Population Density Goal: 24 dwelling units/acre

Services Catchment Area: 15 minutes

Paris started a program to reclaim road space from private vehicles that has since grown into a citywide agenda for remodeling the city into a place where residents can more easily access local jobs, retail, and health and cultural services within a short distance of their homes. Mayor Anne Hidalgo popularized the 15-minute city model in Paris, inspiring localized initiatives such as after-hours access to school playgrounds.

Melbourne, Australia

Population Density Goal: 15 dwelling units/acre

Services Catchment Area: 20 minutes

Melbourne, Australia, embedded principles of the 20-minute neighborhood in its general plan, which has focused on creating walkable neighborhoods that are connected through a mix of land uses, housing types, and access to quality public transportation. It is revitalizing neighborhood activity centers to accommodate key services in each and every neighborhood as well as catalyzing change through investments and policy action.

Charlotte, North Carolina

Population Density Goal: 8 dwelling units/acre

Services Catchment Area: 10 minutes

Charlotte, North Carolina, updated its comprehensive plan, focusing on equity and inclusivity, after a 2014 study found that it had the worst economic mobility among the nation’s largest 50 metro areas. The plan lays out an equitable growth framework that builds on the community’s input regarding long-standing disparities and inequities.

Planning for Equitable Growth in San José

San José, like many other major urban areas across the country, experienced a sustained period of growth after World War II, when land uses began to prioritize cars and ease of driving. Zoning requirements led to car-centric, low-density single-uses that helped create and perpetuate racially and economically segregated communities with inequitable access to critical public resources, like parks and public spaces. These zoning requirements also sustained a pattern of development that has collectively contributed to a rising carbon footprint and an increase in commute times, traffic congestion, pollution, and energy use.

Source: Sergio Ruiz

Lack of Housing Density

San José has more single-family residential zoning than many other large Bay Area cities. Its average housing density is 1,923 per square mile or three dwelling units per acre. The city's general plan outlines a wide variety of living and working environments, continued development of downtown, preservation and improvement of existing residential neighborhoods, and creation of vibrant urban villages. However, data show that more than 80% of San José’s existing residential zoning is dedicated to single-family homes. Reimagining and reinventing San José’s urban form will require the city to holistically redefine and re-envision its growth to realize complete communities.

Income Disparities Among Races and Ethnicities

San José is among the wealthiest cities in the country by household income, yet income disparities across racial and ethnic lines curtail socioeconomic opportunities for individuals and families living in the city. These disparities must be acknowledged and accounted for if the city is to effectively plan for housing affordability and anti-displacement as well as improve accessibility to employment and education and increase community cohesion.

Patterns of Community Disinvestment and Segregation

An analysis of San José neighborhoods’ proximity to the services and amenities specified in Moreno’s 15-minute city model shows that historic patterns of community disinvestment and segregation persist in some neighborhoods (particularly in the Eastside). Alum Rock in East San José exhibits less proximity to services and amenities than most neighborhoods in West San José. Further data gathering could inform the city’s approach to reforming or creating policies to counteract these patterns.

Urban Villages: A Strategy for Achieving Equitable and Complete Neighborhoods in San José

Since 2016, San José has planned and approved 14 of its 60 designated urban villages, each with a commercial square footage target and housing unit cap. The villages, embedded within the city’s general plan, represent a key land use strategy for concentrating sustainable, high-density, and mixed-use urban growth in locations accessible by existing transit or by walking and biking. The villages are designed to disperse employment across the city, to grow or create clusters of activity, to ensure that retail and other local services are available throughout the city, and to create opportunities for small businesses, small tech firms, and start-ups.

Until recently, urban villages and other residential projects in San José could be developed only in accordance with established “development horizons” (that is, time frames for development), essentially placing a moratorium on new housing. Today, state legislation and city-sponsored policy adjustments have eased that moratorium. But housing remains difficult to create. Despite this challenge, urban villages provide a policy framework — alongside local and regional transit-oriented communities policies, “complete streets” design guidelines, and placemaking strategies — to enable the establishment of more complete, walkable neighborhoods.

SPUR believes the 15-minute city concept can be a powerful tool to inform and support the urban village policy framework. Most importantly, it can offer San José’s elected officials, city staff, and community stakeholders a shared vision of complete and connected neighborhoods that they can build together.

Stay tuned for our policy brief and other tools this fall.

Work underlying this article and the upcoming policy brief and tools is supported by The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.