It’s a physical fact that sea levels will continue rising into the 22nd century and beyond, with the pace of rise accelerating each year. Over the past decade, California and the San Francisco Bay Area have deeply invested in understanding the region’s vulnerabilities to climate change impacts such as sea level rise and coastal flooding, evinced in reports such as the Baylands Goals Update, ART Bay Area and the Ocean Protection Council’s sea level rise guidance. We in the Bay Area now know what hazards we are likely to face, even if we don’t know the timing of their impacts. With legislation such as Assembly Bill 32, Senate Bill 375 and Senate Bill 100, the State of California has helped to forge a public consensus that governmental action on climate change is important and that the state can lead. Strong networks of local governments (CHARG, BAYCAN), regional agencies, public campaigns (regional Measure AA, Foster City Measure P and San Francisco Prop. A), policy organizations, business groups, and multilateral efforts such as Resilient by Design and 100 Resilient Cities have engaged the public and increased support and resources for action on resilience.

But scientists have handed a harsh reality check to those who work on San Francisco Bay restoration and flood risk: For nature-based adaptation measures such as tidal wetlands to be effective against rising seas, they will need to be in place within the coming decade, meaning the region must now implement shoreline projects with unprecedented speed.

Even though more people than ever are interested and willing to do something to secure a resilient future for the region, we face major challenges:

- Institutions lack an understanding and a consensus on what to actually do

- Institutions lack a shared agreement on roles: who should do and lead the work, and at what scale

- Frontline communities, who will be hit first and hardest with flooding, have less access to implementation dollars and technical support

- The public is preoccupied with other funding crises, such as the housing shortage and homelessness

- All scales of government lack agreement and understanding on who should pay for adaptation, how much to spend and what the public is willing to pay

Over the last three years, our organizations, SPUR and the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), developed the San Francisco Bay Shoreline Adaptation Atlas. The atlas proposes a new framework for sea level rise planning by dividing the 400-mile Bay shoreline into 30 distinct operational landscape units or OLUs — geographic areas that share common physical characteristics such as shoreline type and watershed processes. OLUs are typically bigger than a city and smaller than a county. Together they contain most of the area in the region that is potentially subject to the geomorphic, hydrologic and ecological effects of sea level rise over a relatively long time horizon: 100 to 150 years. Each unit is large enough to encompass the major physical and ecological processes that determine adaptation possibilities for the shoreline, yet small enough for people to organize around and effectively manage. The Adaptation Atlas provides substantial geographical information about each OLU, discusses measures that can be used in planning for sea level rise and explores the suitability of these adaptation measures for each OLU. Measures explored include policy ideas, financial approaches, traditional grey infrastructure, and green infrastructure measures that harness natural processes to achieve desired results.

OLUs and the Adaptation Atlas have proven to be a useful and supportive framework for adaptation planning efforts by San Mateo County, Marin County, the Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s (BCDC) Adapting to Rising Tides Bay Area initiative, and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and Association of Bay Area Government’s (MTC-ABAG) Horizon Futures project. We believe this framework succeeds for two reasons: it foregrounds nature-based solutions to resilience and it’s based on a process that seeks local consensus regarding appropriate measures.

The Proposal: Four Key Actions

Between the Adaptation Atlas, the success of Measure AA, a number of recent pilot adaptation projects and other new science-based tools, the Bay Area now has a number of processes underway to address the impacts of climate change on the Bay shoreline. To bring all of these efforts together and make sure they complement — rather than compete with — one another, BCDC recently launched a Regional Shoreline Adaptation Strategy. SPUR and SFEI have consulted on and support this strategy, explained in Key Action 1 below. We also propose three other policy ideas for how to govern adaptation strategies across the region.

Our proposal is based on three overarching ideas. First, when planning is not community-based and community-driven, it will not be community-owned and will not succeed — something that the region’s frontline communities have said repeatedly in many settings. Second, the region can marshal a willing collaboration of state, regional and local agencies to outline an approach that prioritizes consistency and fairness, and the state can bring technical resources, support and funding. And lastly, adaptation must be nature-based — meaning green and hybrid solutions — if we have any hope of saving the rich ecological environment of San Francisco Bay.

Key Action 1. BCDC and MTC-ABAG, with key agency partners, should develop regional guiding principles and a consistency framework for certifying local planning efforts and recommending them for funding.

Regional guiding principles for local adaptation planning are needed to ensure fairness between jurisdictions and an inclusive planning process, and to maximize consideration for nature-based solutions. A new effort led by BCDC is pursuing this idea with the participation of the Bay Area Regional Collaborative, MTC-ABAG, the Regional Water Board, the Coastal Conservancy, local governments and other partners. The Regional Shoreline Adaptation Strategy (RSAS) aims to develop a joint platform of guiding principles and a suite of priority actions for adaptation across agencies and stakeholders, building on the strong foundation of science, research, planning and projects already occurring throughout the Bay. The RSAS has engaged the business community, local governments, flood protection agencies and environmental and planning-focused groups such as SPUR and SFEI to participate in developing this platform.

The success of the RSAS will lie in all of these entities agreeing on and implementing a common set of priority actions. We propose Key Actions 2, 3 and 4, discussed below, as a framework for creating plans at the local level that can then garner regional cerfication and follow a path toward funding and implementation.

Once completed, the joint platform should be used to vet and certify local coastal adaptation plans (see Key Action 2) based on their foregrounding of nature-based adaptation solutions, the latest sea level rise science and projections, a true community-driven process and a “do no harm” framework where one local or OLU-scale plan shall not have negative impacts on others. A regional framework will help to prevent conflicts between neighbors, and it will help counties and their community partners verify that their proposed approach meets regional goals. As a benefit of developing plans consistent with the platform, counties should receive priority permitting for shoreline projects and have access to regionally controlled and distributed resources for planning and implementation.

This process should be completed as soon as possible to provide guidance for local plans, which are likely to take at least a year to create. The regional agencies can also participate in local OLU-based planning processes to represent and share information and to consider the impacts and adaptation opportunities presented by regional infrastructure that crosses OLUs, such as highways and railroads. The agencies should use the Ocean Protection Council’s guidelines to consider options for protecting, relocating or changing the physical form of these assets to respond to flood risks and hazards.

The agencies could fund an organization such as CHARG to develop subregionally specific sea level rise projections, to include Ocean Protection Council projections and to account for factors of subsidence, vertical land motion, fluvial and combined flooding, and other factors that might influence vulnerability by location. CHARG could also be funded to develop regionally consistent technical specifications for engineering and construction solutions. For example, neighboring OLUs should construct levees at the same height, but currently there is no shared guidance about the technical specs of adaptation infrastructure, particularly for nature-based measures.

The regional agencies could also fund additional research, such as through Dr. Mark Stacey’s lab at the University of California, Berkeley, to model the impacts of different adaptation measures to test their interactions. For example, initial modeling has shown that hardening shorelines in one part of the Bay can have negative impacts in other parts of the Bay. The regional agencies can develop guidance and approval processes for OLU plans that reflect a do-no-harm framework.

Just as the California Coastal Commission reviews and approves local coastal plans, the regional agencies — perhaps led by BCDC — should develop a process for certifying local plans in a consistent and simple way. This process would not give these agencies any additional land use authority or zoning controls. It would only allow them to review plans for consistency with adopted regional principles and verify that the plans were developed with an open public process, use nature-based solutions to the extent possible, and incorporate the best available sea level rise projections and science.

Following approval and consistency with a regional framework, lead agencies at the local level should be able to access regional resources in service of implementing early actions in the Regional Adaptation Plan described in Key Action 3 below.

Key Action 2. Counties should create and support development of coastal adaptation plans for every OLU.

Counties should organize and support community-based, collaborative adaptation planning for each OLU, using an adaptation pathways approach (explained in Step 6 below) at the local level. These plans should be updated every 20 years based on new vulnerability information, community engagement and the presence of existing flood control or nature-based adaptation solutions, especially any pilot or experimental projects. These would be inclusive processes involving stakeholders, land owners, public participants, and key agencies in each OLU and would be coordinated and led by counties.

In the Adaptation Atlas, we propose a six-step model for how to use the OLU framework in adaptation planning (see pages 180–181), an approach piloted in Marin County. This model, described below, shows how stakeholders coming together within a particular geographic area could identify their shared sea level rise-related problems, come together to consider adaptation options, evaluate tradeoffs and be ready to change course in response to observed climate changes over time. Importantly, before such a planning process can begin, all the stakeholders who need to be involved should be engaged and supported to participate in the planning process with what they need to do so: whether that is compensation, food, childcare, translation, or needs to be identified by them. (A good model to follow may be found in the LA SAFE plan for Southeast Louisiana.) The adaptation planning process should not just include relevant city and county staff and representatives from NGOs such as environmental organizations, but anyone who would be interested in the future of land use in the OLU: property owners, neighborhood groups, residents, businesses, faith-based organizations, utilities, youth and others. This “big tent” engagement is essential to moving beyond thinking of adaptation as an environmental issue. The pace of sea level rise will force deeper consideration about land use change and other community issues than simply choosing among different types of flood protection.

County governments, flood control districts and other government agencies could be ideal leaders and organizers of the process — and many are already serving in this role (a great example is San Mateo County). However, other community-based organizations could be delegated to take the lead, or co-lead. The leading organization(s) should have the capacity and tenacity to facilitate a planning process, to see that process through, and to work with regional agencies to obtain certain approvals at the end, which would unlock significant funding for implementation.

There are a number of ongoing planning and implementation processes underway to address shoreline adaptation in the region. These efforts should be supported and included in new OLU plans, for example: SB1-funded projects, the Resilient 37 project, Hayward Area Shoreline Planning Agency projects and others.

Following this “getting organized” step, we propose a six-step planning process for each OLU:

- Assess vulnerabilities, exposure and risk to sea level rise in each OLU. This step is already underway in many parts of the region as part of BCDC’s Adapting to Rising Tides (ART) Bay Area program. The goal of vulnerability assessment is to understand which assets are vulnerable to flooding (and what kinds of flooding) in different sea level rise scenarios. In addition to ART Bay Area, some leading counties have conducted their own vulnerability assessments, such as San Mateo County’s Sea Change SMC and Marin County’s BayWAVE.

- Identify and select adaptation options, focusing on nature based strategies in each OLU. Stakeholders participating in the planning process should identify suitable options for the OLU, understand which vulnerabilities different options address, and determine what physical configuration would maximize the effectiveness of a particular adaptation option. This step would ideally be supported by technical experts such as SFEI and the California Coastal Conservancy.

- Consider desired futures and goals. In this step, stakeholders work with each other to determine and describe specific goals the OLU strategy needs to achieve. For example, to maintain a function or service (such as road use, wastewater treatment or a public park) at a particularly vulnerable location until 2050, or to hold the line against regular flooding at a particular location for 25 years. This step might take the most time to build consensus around, but developing a shared vision for resilience outcomes is essential. Steps 2 and 3 can be concurrent or iterative.

- Create scenarios by combining the adaptation measures needed to achieve each goal. Stakeholders should work together to develop a scenario, or combination of measures, to achieve each desired goal outlined in Step 3, considering the co-benefits and/or disadvantages of each combination.

- Evaluate tradeoffs and prioritize scenarios. Once scenarios have been drafted, they can be compared or evaluated for tradeoffs, including cost, benefits to people and wildlife, impacts on transportation and more. Stakeholders should try to achieve consensus on a preferred scenario.

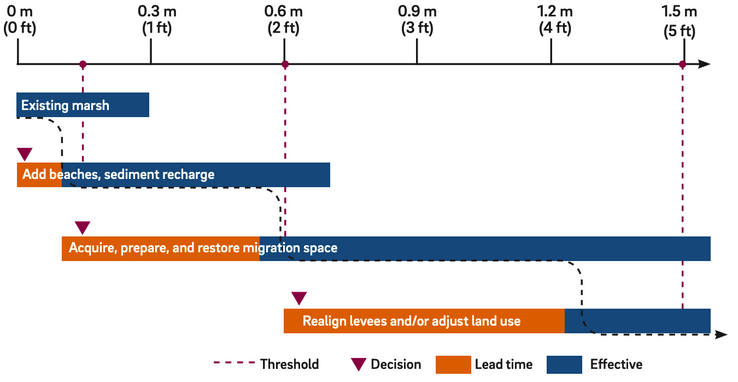

- Develop adaptation pathways to achieve the preferred scenario. Adaptation pathways are a way to address uncertainty in future projections of climate change and allow for flexibility and adjustment over time (Adaptation Atlas, page 63). An OLU adaptation pathway would include measures to pursue immediately to reduce flood risk and improve habitat quality, measures to pursue later as sea level rises, and measures to pursue in the future when flood levels may become intolerable and threaten human health and property. The pathway would take into account existing and projected future vulnerabilities faced in that OLU. But it would not specify when to implement each measure. Instead, it would propose a phased implementation, with each phase triggered once certain thresholds are reached (e.g., a specified amount of sea level rise or frequency of flooding).

Structure of an Adaptation Pathway

The adaptation pathways should be organized and formalized into a document that lead agencies could then use to seek approval and a consistency declaration with the regional agencies’ shared platform, as described in Key Action 1. This framework of a local process followed by regional approval would be similar to what the Coastal Act requires on the Pacific coast of California, where local governments develop local coastal plans and the California Coastal Commission approves them. However, the Bay coastal adaptation plans would be more stakeholder-driven and would need to be updated every 20 years as explained above.

Adaptation pathways are an ideal way to implement strategies to achieve goals or visions. To reach this step, as discussed above, communities must be involved in the planning process from the beginning, and decisions should emerge from a community driven-perspective. Cross-jurisdictional planning at the local level already has precedents in the Bay Area, for example, along the Hayward shoreline, Highway 37 and Lower Sonoma Creek and in Sunnyvale. These existing efforts should be supported through this approach and should not be asked to start over.

Key Action 3. MTC-ABAG should develop a regional funding model and a Regional Adaptation Plan to prioritize projects and the funding to implement them.

Similar to the way the Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) establishes a plan for funding transportation projects proposed by counties, MTC-ABAG should develop a process for soliciting and funding resilience projects from counties and putting them forth in a Regional Adaptation Plan. This would follow the development and completion of BCDC’s RSAS joint platform. MTC-ABAG should make funding conditional upon counties’ demonstration of project consistency with the regional platform and with local OLU-based plans and consider fiscal constraints, as is done in the RTP process. The Regional Adaptation Plan should be updated every five years and the funding model should draw on federal, state and regional funds. Working with Caltrans, MTC should also assume primacy for planning for regionally significant infrastructure, such as highways that cross multiple OLUs, to ensure consistency.

The Regional Adaptation Plan should identify a process for distributing new resources and funding for local projects according to social vulnerability, need, near-term impacts, habitat value and other criteria to be determined. Some portion of these new resources could be used to support planning and adaptation for regional infrastructure, such as roads that cross multiple OLUs and must be planned for as a single asset. An economic study could be conducted for the Regional Adaptation Plan to highlight the costs and benefits of taking action on coastal flooding and sea level rise. Such a study could also identify the cost of inaction.

Like the RTP, the Regional Adaptation Plan could be incorporated into Plan Bay Area, or it could be developed through a separate process.

Key Action 4. The Bay Area legislative delegation, working with regional and local partners, should seek state and federal funding for adaptation.

Legislators should seek state and federal funding to support local planning efforts, significantly invest in implementing the proposed solution set for each OLU and support the Regional Adaptation Plan. To sequence the funding over time, OLUs whose people, natural assets and infrastructure are most vulnerable to nearer-term flood impacts should be prioritized for both planning and implementation resources. State and federal money should also be prioritized to support planning and implementation for vulnerable assets that cross OLUs, such as roads and railroads.

Adaptation planning and flood control are currently funded through various sources. The majority comes from voter-approved bond funding at the state and local levels (such as Prop 1, Prop 68, Regional Measure AA, San Mateo County Measure K). Some comes from property-linked fees such as benefit districts (Alameda County Flood Control District) and ad valorem taxes (Marin County Flood Control District). Federal money supports certain shoreline projects and studies of wildlife and flood control, such as those conducted by the Army Corps of Engineers (South Bay Shoreline Study, San Francisquito Creek JPA study), and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project). FEMA has a grant program to support local hazard mitigation planning and provides disaster relief funding for federally declared disasters.

Many projects cobble together funding from several of these local, state and federal sources at various phases in their scoping and implementation. However, there is no one source of funding that could be used to pay for all of the activities needed to implement offshore, onshore and inland measures that might be identified in local plans. To adequately accelerate and incentivize development and implementation of these plans, a larger, long-term and more secure resource is needed.

The regional agencies that develop the joint platform and guiding principles — perhaps shepherded by BCDC’s Financing the Future working group — could fund a study to identify key opportunities for adaptation funding in a more significant way. Some of the revenue opportunities they could consider are:

- A large state or federal appropriation. Other large urbanized regions in the U.S. receive more consistent federal funding for their environmental efforts than the Bay Area, such as Puget Sound and Chesapeake Bay. Funding could be administered through the San Francisco Estuary Partnership (SFEP), the California Coastal Conservancy or another nonregulatory regional agency.

- A regional trust fund for adaptation. A trust fund — a savings account for future adaptation needs — might be modeled after the New York Regional Plan Association’s proposal to create statewide trust funds to finance coastal adaptation. Such a fund could be capitalized by insurance surcharges or impact fees.

- A regional Geologic Hazard Abatement District. As described in the Adaptation Atlas (page 110) a GHAD is a property-based fee that can pay for maintenance, monitoring of hazards and other upgrades necessary for flood protection and erosion management, thereby providing long-term security of property values, or a form of insurance for probable geologic issues. This might be simpler to enact within individual OLU plans than regionally, especially where property-related fees are already used to fund flood control projects. However, regionwide resource-pooling would help smooth the costs of adaptation in under-resourced and more vulnerable areas.

- A regional revolving loan fund. This fund would be capitalized by a federal investment, like the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, and offer below-market rates. Savings on insurance premiums from improved ratings under FEMA Community Rating Systems, among other sources, could repay the funds.

- A regional Transfer of Development Rights program. Such a program would sell credits to developers through an auction process to build additional density in designated low-hazard areas agreed upon by local governments, and use the funding for adaptation. The goal is to site new development away from high-hazard areas.

- A regional ballot measure. A nine-county measure could raise taxes or a bond, direct bridge toll money, increase the property tax levels currently assessed for Measure AA or otherwise raise revenue to pay for adaptation measures.

Generally, a large infusion of state and federal resources — options 1, 4 and/or others to be determined — is needed to incentivize and support the development of local plans and to establish a semi-consistent level of funding. The economic study for the regional plan could include an assessment of cost or need in order to arrive at a sufficient and meaningful regional funding level. Regional leaders can then work with the Bay Area’s state and federal legislative delegations to develop a shared budget request.

Conclusion

With these four key actions, our proposal identifies the right scale for collaboration to identify adaptation challenges and opportunities, puts communities at the forefront of planning both shoreline and land use changes over the long run, provides regional agencies a way of supporting these efforts while protecting regional interests, and suggests new revenue sources at the state and federal levels to avoid competition with other public needs for local funding.

We now know a lot about climate vulnerabilities and their solutions. It’s time to start making changes on the ground to build regional resilience to accelerating sea level rise. These four key actions identify a way to move forward.