San Francisco and Oakland will spend a combined $29.5 million in soda taxes this year. Now that elected officials have passed budgets in both cities, we can answer two questions: How do both cities plan to spend the revenue? And have San Francisco and Oakland followed the recommendations of their respective soda tax advisory committees?

Voters in both San Francisco and Oakland passed taxes on soda and other sugary beverages in 2016 with the intent that the revenue would be spent on improving public health. However, neither city passed a specific tax, which would have required a two-thirds majority to pass. Instead soda tax advocates pushed for a general tax, which only needed 50 percent plus one vote. Following the model set by Berkeley in 2014, the law directed the tax revenue to the city’s general fund and established a special advisory committee to provide non-binding recommendations for how to spend the revenue.

This past year, the advisory committees in San Francisco and Oakland both made nonbinding recommendations. However, elected officials in each city followed the recommendations to dramatically varying degrees.

San Francisco

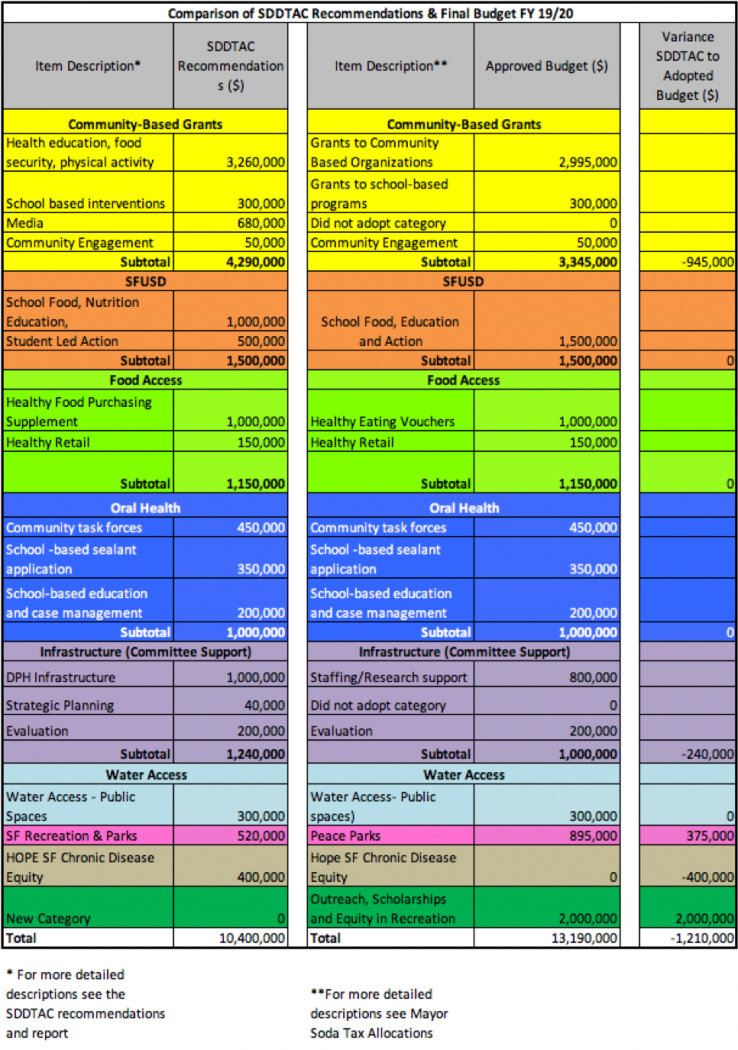

San Francisco’s advisory committee is called the Sugary Drink Distributor Tax Advisory Committee (SDDTAC) and has 16 members from both the city government and community organizations. For the fiscal year 2019–2020 budget, the SDDTAC was charged by the mayor’s budget office with making recommendations on $10.4 million in soda tax revenue. The committee released its recommendations in March, Mayor London Breed released her proposal on how to spend the funds in May and the final city budget was approved in June. The mayor’s budget included an additional $1.2 million in revenue, based on updated projections provided by the controller’s office. The table below illustrates the differences between SDDTAC’s recommendations and the approved budget:

In San Francisco, the Board of Supervisors and mayor adopted the vast majority of the SDDTAC recommendations. The most significant change made by the mayor was the inclusion of a new category for funding: outreach, scholarships and equity in recreation. In the mayor’s press release, she described these funds as expanding free recreation programming for children in shelters and public housing as well as expanding current scholarship programs providing discounted or free recreation programs to low-income families. The San Francisco Recreation and Park Department did not request this funding from the committee, so it was not considered in their deliberations. In a letter supporting the overall allocation of the soda tax revenue, SPUR urged the mayor to ensure that all city departments and organizations follow the outlined process and bring requests for funding to the SDDTAC. Adhering to the committee process supports the credibility of the city’s commitment to uphold the intent of the soda tax ordinance.

The second largest change was reducing the community-based grants category by almost $1 million. The majority of this reduction came from not allocating any revenue to media projects. This category was created to fund four different types of media campaigns: community-led story telling focused on the impact of the soda tax revenue in communities, a regional campaign in collaboration with surrounding jurisdictions, retailer education and an education campaign focused on the dangers of soda consumption. In response to this lack of funding, the SDDTAC wrote to the Board of Supervisors requesting they amend the budget to include the previously requested $680,000 for media. But the supervisors did not change the allocations on this item before passing the mayor’s proposed budget. This aside, the majority of the SDDTAC’s recommendations were adopted.

Oakland

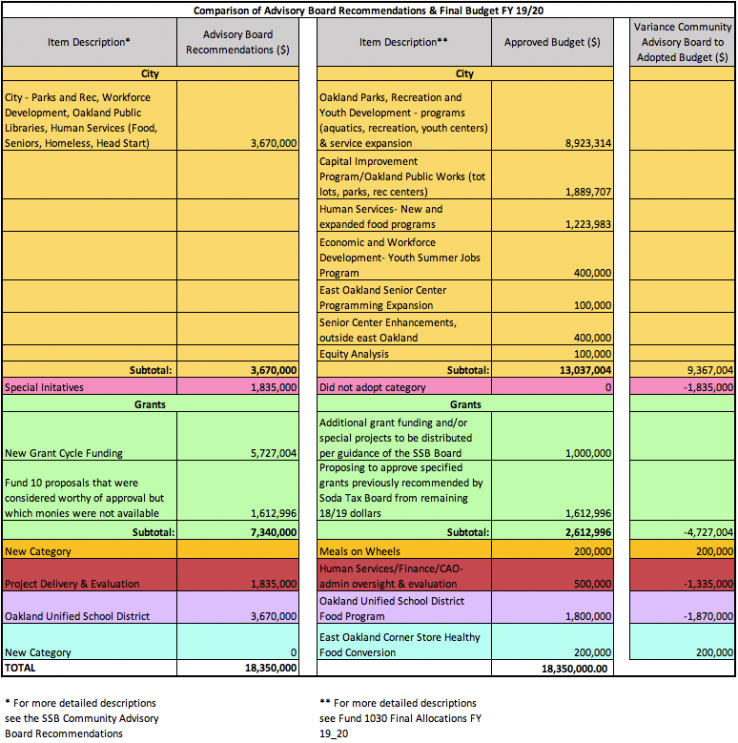

In Oakland the advisory committee is called the Sugar Sweetened Beverage Community Advisory Board and has 9 members including residents, public health professionals and Oakland Unified School District parents. The Community Advisory Board had $18.35 million to make recommendations on, which included both roll-over funds from fiscal year 2018–2019 ($8 million) and anticipated revenue for fiscal year 2019–2020 ($10.35 million). The Community Advisory Board completed their recommendations in May 2019. The Oakland City Council approved the final allocations July 1. The table below illustrates the differences between the Community Advisory Board’s recommendations and the approved budget:

In contrast to San Francisco, the Oakland City Council and mayor did not adopt the majority of the Community Advisory Board recommendations. The most notable change was the council’s increase of final allocations to city departments. The Community Advisory Board recommended 20% of revenue to support city programs across a range of departments with no percentage defined for any single department. The council’s final budget allocated more than 70% of funds for city departments including nearly 50% of overall revenue ($8.9 million) for Oakland Parks Recreation and Youth Development (OPRYD), according to SPUR’s analysis. The nearly $9 million will fund aquatic and recreation programs, youth centers and service expansion. The additional funding above the Advisory Board recommendations for OPRYD is in line with a June 2018 Letter (see page 16) to the city administrator from three City Council members. They requested that the Community Advisory Board develop recommendations with at least 50% of soda tax revenue allocated to OPRYD. The Community Advisory Board did not integrate their request into the recommendations, and in the end the City Council overruled the Community Advisory Board’s recommendations and included this priority.

The only recommendation funded in full was a subsection of the grants category. As outlined by the Community Advisory Board, this category set aside funds for a grant program for community partners that work in five focus areas: Prevention through Education and Promotion, Healthy Neighborhoods and Places, Health Care Prevention and Mitigation, Policy and Advocacy, and Healthy Food Business Technical Assistance. Within this broad grant category there are two separate line items: funding for community partners who applied for funding last year and ongoing grant funds. In November 2018, the Department of Human Services released a request for proposals that was funded from fiscal year 2018–2019 soda tax revenue. 14 proposals were highly recommended for grants by a review panel and received funding. 10 proposals were recommended (those ranked 15 through 24 in this document) but not funded due to budgetary constraints. This year the Community Advisory Board recommended those 10 grants receive funding and the City Council adopted that recommendation into the final budget. The rest of the category for ongoing grants was cut drastically: The Community Advisory Board recommended over $5.5 million in community partner grants, and the City Council approved just $1 million.

Despite a similar process for allocating soda tax revenue in San Francisco and Oakland, the difference in outcome is stark. And, while it is difficult to pinpoint any one reason there are a few possibilities. First, the overall budgeting process is much clearer in San Francisco than in Oakland. Oakland is also facing greater financial insecurity. Both of these reasons may explain why San Francisco adopted drastically more of the advisory board’s recommendations than Oakland did. To explore this question further, SPUR will host a public forum, Soda Taxes: Where Does the Money Go? on October 17.

SPUR will continue tracking soda tax revenue and how it is spent and will post an update when more information is available.

Additional links:

San Francisco Advisory Committee’s recommendations for 2019–2020

San Francisco’s final soda tax allocations, approved by Mayor Breed

Oakland Community Advisory Board’s recommendations

More on the Oakland City Council’s allocations of soda tax revenue