As Jason Roberts puts it, “We all want to live in places that look like this….

….So why do we keep building places that look like this?”

That’s the question that inspired Roberts to make changes in his community in Oak Cliff, a first-ring suburb of Dallas. It started with making a bike lane with stencils and duct tape and hosting an art party in an old, vacant theater. It grew to a new business, a new career and $23 million to bring back a streetcar system to his city.

Roberts, the founder of Team Better Block, presented at an evening forum at SPUR San Jose last week. (See his full presentation.) As his story goes, Roberts was a musician and IT consultant who just wanted a coffee shop and bike lane in his neighborhood. But he found that even the simplest streetscape improvements were too expensive or, worse, illegal under the city’s municipal code. Just adding café seating and an awning cost $1,000 each, not including the cost of furniture.

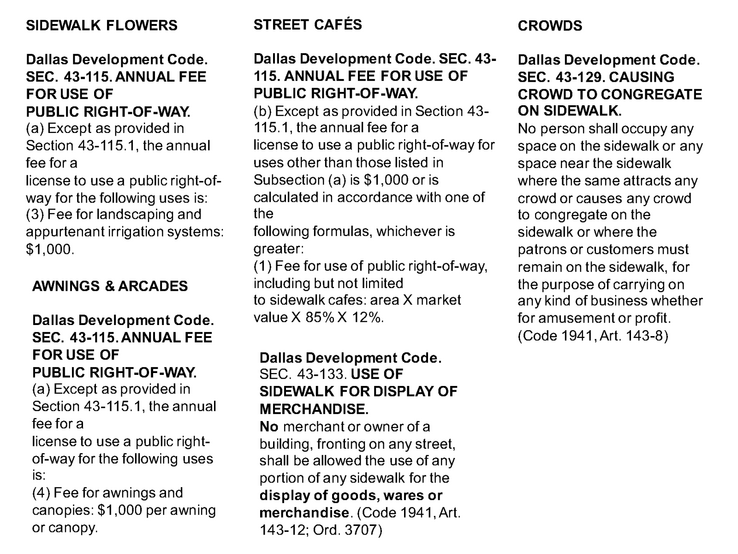

Dallas Development Code

Before the first Better Block project, city codes outlawed crowds on sidewalks and charged prohibitive fees for improvements like planting flowers and putting up awnings.

Rather than getting the rules changed, Roberts and his friends decided to “just break every law at the same time” and invite everyone, including city councilmembers, to a block party to see what they were missing. The first Better Block was a lasting success. City Hall dramatically reduced permitting fees and peeled back ordinances that had banned street activity. Some of the pop-up businesses have since become permanent.

It’s a prime example of “tactical urbanism” — low-cost, temporary, do-it-yourself projects meant to make communities better to live, work and play in. Local iterations include San Jose’s art crosswalks, PARK(ing) Day and the Market Street Prototyping Festival in San Francisco.

Roberts didn’t stop at Dallas. Last year, he and Team Better Block created a nonprofit organization called Better Block Foundation, which educates and equips people with downloadable guides, podcasts and toolkits to create vibrant neighborhoods all over the country—one block at a time. It’s an important part of their work, for as cities begin to embrace and even regulate urban prototyping, the novelty of a few well-intentioned citizens “breaking every law at the same time” will wane. And even now, not everyone can get away with doing so. (Even if, as Roberts suggests semi-seriously, they’re wearing an orange vest while installing unsanctioned streetscape improvements.) The best possible outcome for the tactical urbanism trend isn’t a thousand pop-up projects around the world, but repealing the city codes that made street life illegal in the first place.

Tactical urbanism has always existed. It’s become mainstream as a workaround solution to restrictive municipal codes, prohibitive permitting processes and a lack of funding for more permanent improvements. Now the real work begins: legalizing good urban design and lively communities for the long term.