Throughout its nearly century-long history, the Oakland Produce Market has served as the late-night link between rural farms and urban consumers in the East Bay. The oldest American operation of its kind still using original facilities, the market is a hidden gem in the historical industrial district near Jack London Square. Many of the East Bay’s beloved independent markets — including Monterey Market and Berkeley Bowl in Berkeley, and produce vendors in Oakland’s Chinatown — go directly to the vendors in Jack London because of the high quality produce they offer.

Throughout its history, the market has survived moving, shrinking and losing business to the rise of big-box grocery chains. As jobs, retail and housing continue to move into the Jack London District, will the market remain? That question has actually been on the table for the last 50 years — and so far the market has proven surprisingly resilient.

Early Origins

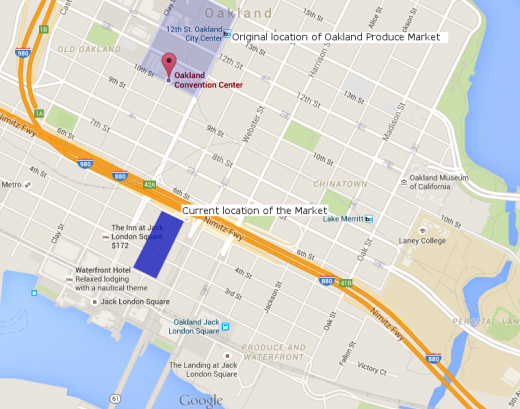

The very first produce market in Oakland was located near 11th and Washington streets, the current location of the Oakland Convention Center. But as the city expanded, the market came under pressure to make way for civic buildings and commercial growth. A 1917 city ordinance encouraged the produce vendors to move by allowing them to display their merchandise on the sidewalk — if they moved closer to Jack London Square.

A 1917 city ordinance encouraged produce vendors to move from Oakland’s Civic Center to Jack London. The market now occupies buildings along both sides of Franklin between 2nd and 4th streets

Luckily, this new location near the port and the Transcontinental Railroad allowed the produce market to expand substantially. The members of Fruit and Produce Realty Company jointly acquired land between Broadway and Harrison Street, from 1st to 4th streets.

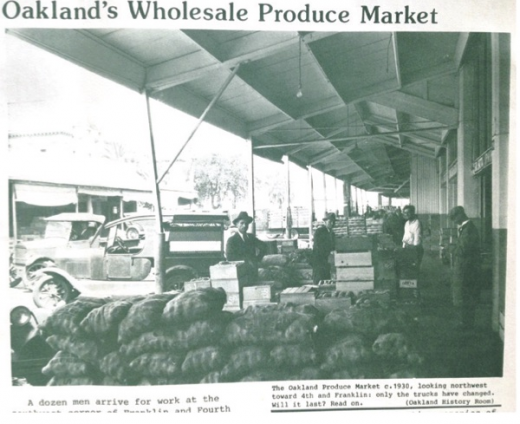

The Oakland Produce Market at 3rd and Franklin circa 1930. (OHA Photos 1987, courtesy of the Jack London Improvement District)

For five decades, business was booming: Major grocers, small markets and restaurants all bought from the produce market. In the 1970s, groups of individuals began buying in bulk through buyers’ co-ops in order to save money, as people became concerned with the rising cost of food.

However, the market started to decline in the late ’70s as major grocery clients such as Lucky and Safeway grew large enough to create their own distribution centers. Over time, it became less known that the market and its goods were open to the public. Between the late ’70s and late ’80s, the produce market exchanged hands three times, bringing on the debate of whether the market was to stay in Oakland or move elsewhere. In 1985, 60 percent of the market buildings were sold for development. Soon after, rents for the produce vendors doubled, causing some owners to halt business completely and others to consider collectively owning and buying the space or moving. Over the years, potential sites for relocation included San Leandro and the Oakland Naval Base, but none panned out. With nowhere else to go, the market remained at its current location.

The Market Today

Today the market houses 20 vendors in an approximately four-acre area. According to Ron Fujii, owner of Fujii Melons for almost 50 years, three quarters of his business comes from small grocery stores and restaurants. Buyers come to the Oakland Produce Market to hand pick their fruit every week. They are drawn to the market because the vendors often receive the freshest produce, sometimes arriving within 24 hours of being picked. Many of the market vendors support the Bay Area’s local farmers, making the market a key link in the region’s farm-to-table food economy.

Ron Fujii speaking to participants in SPUR’s walking tour of the Oakland Produce Market. Photo by Tori Winters.

Huynh Produce, one of the few distributors with a retail front, mostly caters to markets in Chinatown, restaurants and some liquor stores. Photo by Tori Winters.

Fujii feels that the market is still running because the Bay Area’s appetite for locally grown heirloom varietals keeps them in business. “People in northern California have more sophisticated tastes than anywhere else I’ve ever been,” he explained on a recent SPUR tour of the Market. Many of the distributors have long-time relationships with individual farmers, many of whom grow varieties of fruits and vegetables that don’t exist anywhere else.

Other sellers, such as Michael Huynh of Huynh Produce, say that demand drives what is stocked and agrees that many of the purchasers are small businesses. “We even get liquor stores buying some produce to stock their places because more and more people are asking for fresh produce,” he explained. “I honestly don’t think we’re going anywhere. It feels like the market’s been talking about moving for 60 years.”

Pressures on the Market Today

With land prices around the market increasing dramatically and more people calling the area home, pressure is growing for the market to move elsewhere. Though there are no proposals pending and the site is currently zoned for low-density usage, should a developer bring forward a popular proposal, the zoning code could be amended to allow large buildings on the site. In their current state, the buildings are not usable for much beyond produce distribution.

Alongside these external pressures, the market’s vendors also struggle with facilities that are outdated and could use an overhaul to include refrigeration and better loading docks. Without updated facilities, the vendors at the Oakland Produce Market find it hard to compete with more modernized markets.

While the future is uncertain, one thing is clear: Today the market continues to serve as a hub for the local food industry, connecting rural farms and urban residents through fresh produce.

Special thanks to Savlan Hauser of Jack London Improvement District, Ron Fujii of Fujii Melons and Michael Huynh of Huynh Produce for leading the walking tour in partnership with SPUR.