A New Civic Vision

An introduction to the SPUR Regional Strategy

The SPUR Regional Strategy envisions a more equitable, sustainable and prosperous Bay Area for all and proposes bold strategies to get there by the year 2070.

I. The Place We Love

The San Francisco Bay Area is a place of stunning natural beauty and abundance, of dynamic cities and diverse communities. A center of economic innovation, the region attracts new generations with each cycle of technological evolution. Its progressive social and civic leadership has served as a national model: The Bay Area leads the way on issues ranging from climate resilience to marriage equality and produces elected leaders with national influence. Home to almost 8 million people speaking 112 languages, it is the second-most diverse large metro region in the country. This diversity consistently ranks as one of the primary benefits of living here and continually fuels the region’s economic and civic dynamism.

Whether we were born here or came here seeking opportunity or community, there is a lot for us to love about this place. This is no accident. Our experience of the Bay Area today is a direct result of decisions made by prior generations — like saving the Bay from being filled in, creating the Golden Gate National Recreation Area or founding a company in a Cupertino garage.

Yet with all there is to love about the place we call home, living here can also be a tremendous challenge. Despite our largely progressive point of view and episodic but enviable economic prosperity, the region has increasingly become an untenable home for many. This, too, is the result of past decisions.

An Inclusive Region Becomes Exclusive

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, many Bay Area residents were struggling with the region’s high cost of living. Between 1999 and 2018, over 300,000 households earning less than $100,000 moved out of the region, largely in search of a place they could afford. In 2019, nearly half of Bay Area residents experienced economic insecurity, and it was estimated that over 35,000 people were living unsheltered, making the region’s unhoused population the third largest in the nation. All of this took place at the height of the Bay Area’s longest-running economic boom, a time when the region added 722,000 jobs in a 10-year period and counted 180,000 millionaires. San Francisco alone had (and still has) approximately 75 billionaires among its residents.

Slowly but surely, the region that once welcomed all started to become a place where only the wealthy could live. Between 1999 and 2018, the Bay Area added 625,000 households earning more than $100,000 annually. Across various metrics for income and wealth inequality, the Bay Area ranked as the most unequal region in California, and many Bay Area cities topped lists of the most unequal places in the nation. Parents began to worry that their children would never be able to afford to live in the cities where they’d grown up. Long-standing communities of color began to erode, with San Francisco’s Black population falling by approximately 60% between 1970 and 2019. Four-dollar toast became a symbol of the region’s affordability challenges.

The Bay Area’s famed quality of life began to suffer. Many people drove alone in their cars for two hours or more a day to get to and from work. Decades of underinvestment in public education left families grappling with inadequate or expensive education options. Long commutes took time away from child-rearing, often requiring families to pay more for child care.

At the same time, climate change began to hit home in new and oppressive ways, ushering in a longer, more intense wildfire “season” that in two years destroyed thousands of homes and — for one dark day in September 2020 — created an apocalyptic sky with no sun.

While many in the region share a progressive sensibility, the Bay Area’s inability to shelter people living on the streets became another symbol — this time, one of despair and systemic failure.

The pandemic exacerbated these underlying conditions, but all of them existed before 2020. They evolved through a series of collective decisions that compounded over time, creating structural problems that underpin our reality today. A number of these decisions were enshrined in planning practices and zoning laws in the 20th century, and their impacts continue today.

Passing Redlining Laws

Like the rest of the nation, in the 20th century the Bay Area engaged in racist land use policies and laws that segregated white people from people of color and limited housing options, in particular for Black residents. The places available to nonwhite people were often the most environmentally hazardous: “fenceline” communities near factories and refineries, neighborhoods where freeways were built, areas below sea level. Because federal law limited their access to property ownership, people of color, especially Black residents, were systematically denied access to that quintessentially Californian vehicle for wealth: the home.

Designing Cities for Cars

The polycentric region we experience today — a collection of towns and cities connected by freeways and largely requiring a private vehicle to move around — took shape in the postwar period, influenced by the introduction of the federal highway system and federal subsidies that supported white, suburban home ownership. These policies created a car-dependent culture that exacerbated racial segregation, income inequality and the carbon emissions that cause climate change.

Limiting New Housing

In the following decades, Bay Area cities chose to limit the amount of new housing they built. When the region began to protect its open spaces and contain sprawl, demand for housing began to outstrip supply, with the predictable consequence that housing became increasingly expensive.

This placed pressure on the less expensive communities in the region, the definition of which has shifted geographically as the supply/demand imbalance has grown. Where once Oakland was considered affordable compared to San Francisco, now both San Franciscans and Oaklanders look to cities like Antioch and Vallejo for affordability. Due to the wealth inequality that directly results from racist housing policy (along with other forms of systemic racism, such as educational inequity), white residents enjoy a much greater ability to compete in the market for housing than people of color do. Thus, the Bay Area continues to lose its communities of color to displacement and perpetuates the dynamics of segregation.

Investing in Job Growth — but Not Transit

While Bay Area cities have constricted housing supply, they have largely welcomed jobs. This imbalance exacerbates the region’s already-constrained transportation system, as people travel long distances between where they can afford to live and where they work. Despite decades of population growth, the region has not yet retrofitted its transportation system for sustainability: Most people drive alone for almost all of their trips. With what we know about carbon emissions and their impact on wildfires, sea level rise and other environmental catastrophes, this is a practice that risks the region’s health.

A Collective Challenge

The Bay Area also struggles with a fundamental misalignment between how it operates and how its decision-making and governance structures have been set up. Many people live in one city or town and work in another, often across counties. The wildfires that rage in the North Bay affect people living in the South Bay, and vice versa. One city’s choice to add more new jobs than new homes puts pressure on all of the surrounding communities, especially those that are the most marginalized. In essence, the Bay Area’s challenges are regional in scale, but we rarely address them — or even consider them — from that vantage point.

Like all American metro areas, the Bay Area has suffered from generational disinvestment at the federal and state levels in education, housing and transportation, all of which are necessary components of a healthy community. While we’ve often raised taxes on ourselves to compensate, the scale of investment required is largely beyond what the region can raise itself. As public services like schools and transit decline due to disinvestment, more families must pay for private education or buy a car. But not everyone can afford these costs. Decisions made at the highest levels of government have shifted the burden from the collective — where it is more manageable — to the individual, exacerbating inequities along the way.

The Choice Before Us

If we continue to practice business as usual, we should not expect different results. If we limit new housing supply to one-third of demand, we should expect that the one-third of people who are able to secure new housing will be the wealthiest and — given racial inequity — disproportionately white. If we resist change by refusing to adapt, we should expect to face the same old problems — with increasingly worse outcomes. If we assume that the inherent desirability of the Bay Area will always generate economic prosperity, we are putting that prosperity in jeopardy. And if we accept living in an environment where we can plainly see that so many of us cannot meet basic human needs, we risk replacing our innovative spirit with cynicism.

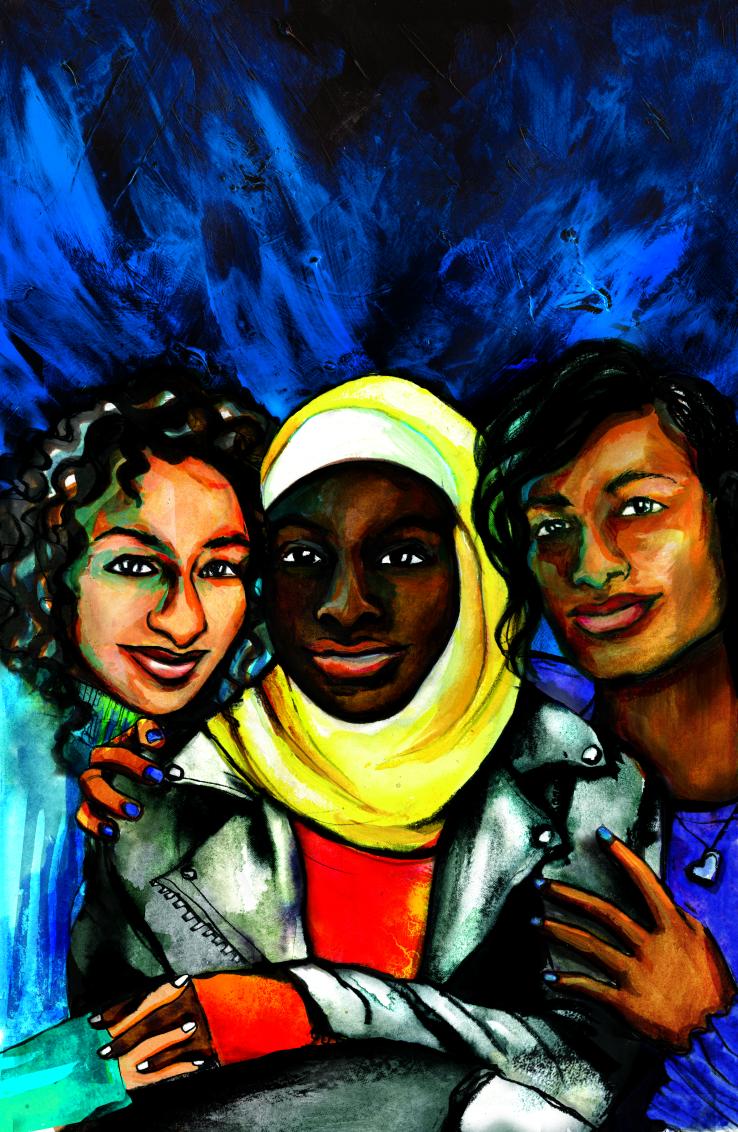

For generations, the Bay Area has been a place where people can find community in pursuit of both liberty and justice for all. Whether it was the Black Panthers organizing the first free meals for schoolchildren in Oakland or César Chávez learning the art of organizing in San José or a gender-fluid teen arriving in the Castro, the Bay Area has offered both refuge and leadership for social change. Faced with challenges, the people of the Bay Area have time and again responded with solutions and with courage, strengthening our collective belief in what we can accomplish.

Today, we can again choose a different future. All of our laws, rules and social agreements about how we treat one another are choices we have made. Which means that we can make different choices, ones that lead to a Bay Area in which all people — those here now, those who dream of living here and future generations — can thrive.

II. A New Civic Vision for the Bay Area

With the Regional Strategy, SPUR has placed a stake in the ground for a New Civic Vision. In this vision of the future, the people of the Bay Area recognize the connection between their individual lives and the broader community. They take collective action to put the pieces in place that will allow all of the region’s residents to thrive.

The American social contract has largely been an implicit agreement that the state will respect individual liberty and, in exchange, residents will work hard to better themselves. SPUR believes the Bay Area can improve upon this, recognizing that individual liberty is essential but insufficient and that, in practice, some people in this country have more rights than others. Instead, the Bay Area can create a social contract that recognizes individual well-being as a function not only of individual liberty but also of community well-being. The COVID-19 pandemic proved that we are interdependent: We now know we must rely on each other to take responsible individual action to keep our communities healthy. So, too, we should be able to rely on — and support — our institutions and governments to safeguard community well-being so that individuals can thrive.

To guide this work, SPUR adopted a set of core values to inform the Regional Strategy’s policy ideas and the vision behind them:

Stewardship: We are all responsible for this beautiful place, for one another and for future generations. All of us deserve clean air, clean water, good health and safety from climate threats.

Cooperation: The Bay Area communities are all in this together. Most of our toughest problems — from housing to traffic to sea level rise — demand regional collaboration.

Equity: Justice is an essential element of a stable, healthy society, and systemic racism requires a systemic response. Policy is a critical tool in this effort.

Prosperity: A thriving economy is essential to provide both jobs and public resources. We cannot take our prosperity for granted.

Leadership: Time and again, the Bay Area has pioneered influential ideas and new solutions. Now more than ever, we should be a model to the nation and the world.

SPUR imagines a future Bay Area made up of thriving, diverse communities that connect seamlessly, allowing everyone to experience the region as a place where they belong. In this future, all people have the basic amenities: shelter, safety, healthy food, clean water, freedom of mobility and a healthy environment. And all people can participate meaningfully in the economy and live in a just and stable society — one where they can count on both institutions and each other to correct injustices if their rights are systematically withheld.

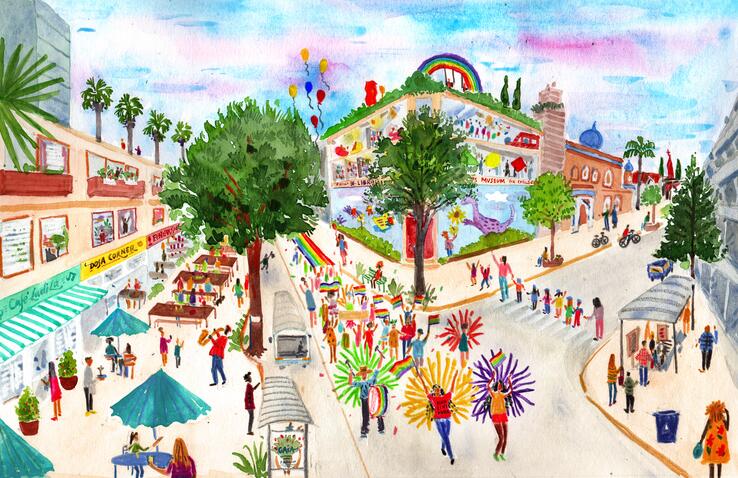

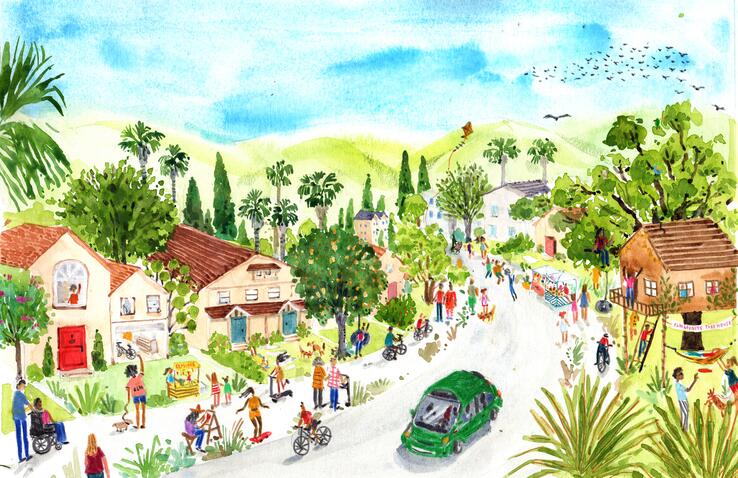

The Bay Area of 2070 has learned how to grow both gracefully and sustainably; its cities leverage growth to improve quality of life. Modest density in walkable, well-connected suburban neighborhoods provides homes for new generations, for long-time residents and for those seeking access to opportunity. Thriving commercial corridors with great transit access offer people places to work, shop and live. Dynamic downtowns provide not just the jobs of the future but also the gathering spaces that enable infinite uses — spaces for art, for celebration, for protest, for casual connection. The region has — finally — created enough homes, up and down the income scale, that anyone who wants to live here can belong in the Bay Area.

In this future, we have fully embraced our essential connection to the natural world that sustains us. We have safeguarded our water supplies so that every resident has access to clean, safe water. We have done our part to stop contributing to climate change, and we have systematically and comprehensively adapted to the climate change impacts we cannot control. We continue to protect our open spaces and agricultural lands and introduce nature into our communities, allowing all people the benefit of green streets, connected trails and places to play.

We experience the Bay Area as one place because we have retrofitted our transportation system to function as a single regional network, making it easy to get where we need to go without having to drive alone in our cars to get there. Our communities are convenient and safe to walk or bike around in; transit is seamless, regional and efficient; and we make the most effective use of our streets and highways.

These transportation improvements create new avenues for connection and opportunity and allow all Bay Area residents to participate in a dynamic economy that embraces the region’s innovative spirit and commitment to equity. We understand that we must collectively contribute to the things that keep our communities healthy, and we allocate our wealth so that our schools, parks, libraries, transit systems and people are well supported. We embrace prosperity because we know that it’s essential for quality of life and because we can see and trust that our prosperity is shared equitably.

We are able to do these things because we have organized ourselves to enable effective regional decision-making and problem-solving, while never losing sight of the unique needs and experiences of our many communities. Supported by a shared commitment to interdependence, our governments coordinate and cooperate at the regional, county and city levels. The broader civic ecosystem of community organizations, advocacy groups, service providers, philanthropy, business organizations and others are similarly effective at coming together to address emerging issues across the region.

And, foundationally, we have individually and collectively acknowledged, interrupted and redressed the impacts of systemic racism. We have used policy interventions, government action, economic opportunity and institutional reform to holistically transform the region from a place burdened by its racist past to a place that offers true and practical equality.

With each step, we residents have felt a little more secure, a little more accepted, a little better able to breathe. We have reached a turning point where there are enough homes for everyone, and fewer and fewer people are living with the fear that one misfortune could leave them without a place to sleep at night. We know the security that comes when communities are protected from floods and wildfires. We know the gift of time people receive when they no longer have to drive to and from and to and from. We know the extraordinary physical and emotional burden that is lifted when people are no longer at risk because of the color of their skin. We know the love people experience when they arrive in a community where they can sense, deep down, that they belong. We know the hope and satisfaction that comes with new job opportunities. We know the creativity and joy that grows when our most fundamental needs are met, when we can trust that we can survive and turn our energy to thriving.

III. Making the Vision a Reality

In order to create the Bay Area we want to live in 50 years from now, we need to begin planning and building today. It is essential but not sufficient to imagine a new future: We must also change the policies that govern where and how we build housing, the type of energy we use to power our buildings and transportation, the way we get around and how we take care of each other. The SPUR Regional Strategy puts forth a series of groundbreaking policy reports organized around five core ideas. When taken together, these policy proposals will help us create an equitable and sustainable future.

Idea 1

Reimagine the Bay Area’s housing policies to treat housing as a human right and make sure everyone has an affordable place to live.

Imagine a Bay Area where our greatest challenge, the scarcity and expense of housing, has been solved. This may sound like an impossible dream, but it isn’t. If we believe that housing is a human right and act accordingly, we can live in a region where everyone is housed and the cost of that housing is not wildly out of step with people’s ability to pay for it. A region where people don’t have to commute four hours a day in order to afford housing for their families. A region where families aren’t forced to live in unhealthy or overcrowded conditions. A region where the relationships that people form in their neighborhoods are sustained through housing policies that keep them in their homes. A region where all people, not just the wealthy, get to flourish and thrive.

To make housing affordable to everyone, we need to:

Treat housing as infrastructure.

SPUR believes that housing is a human right. If we treat housing as essential for humans to thrive, then government must play a more critical role in providing it. For example, the government does not wait for the open market to provide water to homes and businesses; in most communities, it actively intervenes to ensure that this happens. When we approach housing as infrastructure, government takes an active role in producing homes at all income levels. This should include significant increases in funding for affordable housing, support for acquiring existing units to make them permanently affordable, mechanisms to encourage housing construction during economic downturns, reforms in property taxation and ways to radically increase the amount of factory-built housing we produce.

Build 2.2 million homes so everyone has an affordable place to live.

Over the next 50 years, the Bay Area needs to produce 2.2 million homes at all income levels. This housing should be for everyone: formerly homeless people, low- and middle-income residents, families and extended families, seniors and college students, and even those earning above average so they don’t outcompete everyone else. The rules governing the planning and permitting of housing will need to change in order to make sure enough additional housing gets built. These changes should include establishing both requirements and incentives for local governments to change their zoning codes to allow for much more housing.

Protect and support long-time Bay Area residents, especially vulnerable communities facing displacement.

To create an equitable, sustainable and prosperous Bay Area of 2070, we must ensure that the benefits of new infill development are shared by low-income communities and communities of color, which have historically been left out of the region’s growing economy. To do this, we need to protect and support existing residents, align tax policies and incentives to reduce speculation in the housing market and enable low-income households to create wealth, including through homeownership.

Create neighborhoods of belonging.

SPUR envisions that Bay Area communities can evolve into places where people of different races, economic backgrounds and life experiences all feel comfortable and welcome. To create neighborhoods of belonging, we should strengthen arts and culture organizations in neighborhoods experiencing change, find ways to address commercial displacement, encourage equitable practices in new development and educate new residents on how to respect existing cultural norms. We must also ensure that exclusive communities add housing of different types and prices so that people of varying incomes can afford to live there.

Idea 2

Use growth to bring new opportunities into existing neighborhoods, creating more prosperous and diverse communities and protecting open spaces.

What if the word “growth” — so often associated with the world of tech and financial bottom lines — evolved to mean something else entirely? Instead of ever-expanding outward, we would develop and cultivate what we already have. Over the next 50 years, the Bay Area is expected to

gain as many as 4 million people and 2 million jobs. SPUR has identified a set of growth principles that will allow the region to welcome new residents and jobs without paving over green spaces or pushing out long-time community members. If we follow these principles, the region can grow into a place where everyone is housed and has access to quality public amenities. Where people of color are safe and welcome in all neighborhoods and public spaces. Where commuters have time for family and community life. Where all kinds of families, in all types of homes, live in community together.

To grow in a way that supports equity and sustainability, we need to:

Concentrate growth around transit and along commercial corridors, and add housing in existing neighborhoods, including exclusive suburbs.

SPUR’s New Civic Vision calls for the region to add 2.2 million new homes in areas that are well served by transit; in commercial corridors and historic downtowns; in areas with great schools, jobs and amenities; and in existing suburbs. Previously exclusive neighborhoods will become more affordable and welcoming for all. Under this scenario, the region will also add 2 million new jobs in transit-centered areas and downtowns. We can accommodate all of the region’s growth in these areas without growing in open spaces, agricultural lands or hazardous areas prone to flooding and wildfires.

Create great places.

What if we grow in ways that make neighborhoods not only more equitable and more sustainable, but more livable and humanizing places? New growth can enable existing areas to become better places, retaining many of their essential qualities while supporting diversity and inclusion, public health, sustainable mobility and community life. Instead of spending hours commuting in a car, residents can access their daily needs within a 15-minute trip by walking, biking or transit, and most residents can get to their jobs within 30 minutes without driving. At the same time, urban centers in San Francisco, Oakland and San José can become even more exciting, people-friendly places through great urban design improvements.

Stop growing in hazardous areas, open spaces and agricultural land.

Growing outward has many societal costs. It increases pollution and the amount of time people spend commuting in their cars. It also exacerbates climate change, which in turn increases wildfire threats and flooding risks. And it can put homes in places where the danger from these threats is high. These risks especially impact those with low incomes, creating more inequity in our region. Avoiding growth in rural areas also supports the protection of agricultural land and the viability of the Bay Area’s farming communities.

Protect and expand parks and natural spaces, and increase access and usage.

Part of what makes the Bay Area special is its incredible network of open spaces. We need to continue to create and care for these places, whether they are vital links in the regional open space network or small green spaces that anchor neighborhoods. In particular, we must engage communities in the design of public spaces and parks, so they become welcoming to those who have previously been excluded from them, including people of color and people with low incomes.

Idea 3

Close the racial wealth and well-being gap and help build economic security for all people, regardless of their race or income level.

We can live in a Bay Area where economic opportunity is accessible to all people and the social safety net is strong enough to meet basic needs. In this future world, the small but unpredictable events of life — a sick child, a parking ticket — do not swell to become undue financial burdens. We no longer expect poverty to be intergenerational. Instead, we address the economic impacts of systemic racism head-on so that poverty, homelessness and hunger are rare and episodic, not a permanent way of life. We invest in high-quality community services — like education, transit, parks and libraries — knowing that they are essential for economic security. As we work courageously and intentionally to close the racial wealth gap, more people become active in the economy, and the economy continues to grow.

To close the Bay Area’s racial wealth gap, we need to:

Ensure that our shared public services are excellent and available to everyone.

Everyone deserves equal access to high-quality public services and opportunities. Investing in our shared resources, such as libraries, parks and transit, will help remove burdens and meet needs, laying a path to greater economic security across the board. We can build a system of public goods that reaches all people, regardless of their income or neighborhood, and allows people to share in the vast wealth of our region.

Make public assistance work.

Traditional social welfare programs don’t help people fix a broken car, pay an electric bill or buy clothes for a job interview. Programs that give individuals or households money with no specific requirements on how it is spent can help fill these gaps. At the same time, California’s public benefits systems do not reach every eligible person, with some programs missing over a million people who qualify. Ensuring that existing programs are easier to access is an important first step.

Dramatically reduce fines and fees.

Fines and fees are often high-pain, low-gain tools that don’t meet their intended goals and can strip wealth from low-income and working families and communities. California has some of the most costly fines and fees in the nation, but they do little to change behavior like speeding or littering. Low-income people and people of color are more likely to be fined and more likely to struggle to pay fines, creating one of the biggest barriers to economic security and mobility. The Bay Area should look to alternative systems that can promote safety and the social good without creating impediments to economic stability.

Design a fair tax system.

California’s complex and outdated property tax system fails to encourage new housing, disproportionately benefits those who were able to buy homes decades ago and does not generate enough funding for the things we need government to provide. Because property taxes in California remain artificially low, cities and counties look to sales taxes to pay for public goods. But sales taxes also play a role in reinforcing structural inequality. Every consumer pays the same tax rate at the register, but low-income households pay a higher percentage of their income in sales tax. In order to create a fairer system, California’s tax structure needs an overhaul.

Idea 4

Help the region thrive by eliminating our dependence on fossil fuels, increasing our resilience to sea level rise and wildfires and protecting our natural spaces.

Picture a Bay Area where our environment is healthy and protected. Where we develop adaptations to climate change that mirror the genius systems already at play in our environment. For ourselves and for future generations, we clean our air, protect our habitat and restore the ecosystems of our unique plants and animals. The Bay-Delta and its tributaries thrive once again. We eliminate the use of fossil fuels in homes, in business and in transportation. We remember the real purpose of conservation: the joy and security of living in a world that is healthy for all living creatures.

To support our environment and combat climate change, we need to:

Eliminate the use of fossil fuels.

Fossil fuel use is causing runaway global climate change, but we still have time to reverse course if the world can transition to renewable sources for almost all energy uses. California has the most ambitious climate policy framework in the country, and the Bay Area has the resources, political temperament and innovative spirit to demonstrate how to eliminate the use of oil and fossil gas. This means ending our dependence on solo driving, electrifying our transit and passenger vehicles, and using renewable electricity to heat our homes and cook our food. We can prototype ways to become fossil-free, modeling them for cities and urban regions around the world.

Make the region resilient to sea level rise and wildfires.

The Bay Area is both a treasured place and a hazardous environment where flooding, wildfires and earthquakes are common today. These hazards are likely to become more frequent, larger and more damaging as the climate changes. One of the greatest obstacles in responding to climate change is the fragmented nature of the region’s institutions. We must develop coordinated resilience strategies that can be adapted to suit local settings, and government agencies need to collaborate to solve for multiple hazards at the same time.

Treat the Bay-Delta ecosystem as a natural treasure.

The Bay Area’s natural beauty is threatened by climate change, but it can be preserved if we act quickly. Large swaths of land adjacent to the Bay are suitable for green infrastructure projects to provide protection from rising seas and habitat for nature. Bay Area cities also need to ensure that we use freshwater wisely, with an eye to the needs of ecosystems and upstream communities that need water to thrive.

Create a just environment.

Our efforts to restore the environment must also repair environmental injustices. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions must go hand-in-hand with cutting pollution in vulnerable communities. Adaptations to combat sea level rise must support the people who live in areas prone to flooding, many of whom are in low-income communities and communities of color. And making our water supplies more sustainable must happen in tandem with making drinking water safe and affordable for low-income households.

Idea 5

Create a 21st-century transportation system where it’s easy, fast and enjoyable to get around without driving alone.

The Bay Area can be a place where it’s easy and efficient to get from one place to another without driving alone — a place where riding transit, hopping on a bike or sharing a vehicle gets you where you need to go safely and enjoyably. We can reduce carbon emissions by creating great transportation options so that solo driving is not the default choice for most trips. To do so, we need to build a truly regional transit system with easy connections, equitable fare policies and quick, reliable service. We must prioritize road space for pedestrians and for sustainable transportation, such as bicycles and buses. And we should make streets great places for people to enjoy by designing neighborhoods that put people — not cars — first.

To create a 21st-century transportation system, we need to:

Create a seamless transit network that expands opportunity, supports cities and reduces our car dependence.

To make it viable for people to choose transit over driving, we need frequent, all-day transit service arranged in a regular, repeating schedule. This will make transit much more reliable, make trips quicker and require less planning ahead. Once we do this, Bay Area residents will gain more access to more places. Stations will become anchors of public life, and transit will support and sustain our growth. Great local transit is the building block of this network, helping people meet their daily needs and connect to regional service. To deliver on this vision, we need to create express lanes for buses and high-occupancy vehicles on highways, make regional rail service more frequent, complete critical projects that carry more people and enable more service, and build out California’s high-speed rail system.

Coordinate transit services across the region to create better mobility for all.

The Bay Area’s transportation system is arguably the most complex in the country. The region has more than two dozen different public transit operators, all with different schedules, fare policies, maps and apps. This idiosyncratic and fragmented system reinforces inequities and makes it difficult to achieve our climate goals. For an optimal regional transit system, we need to give one institution the ability to coordinate transit operations across a cohesive network, on behalf of all riders. When we do, we can ensure that new service equates to better service and that the transit system functions as one rational, regional network.

Deliver transportation projects quickly, cost-effectively and with better public value.

Around the world, building major transit projects is notoriously difficult. Yet the Bay Area has an especially poor track record: Major transit projects here regularly take decades from start to finish, and our project costs rank among the highest in the world. They also regularly go over budget, forcing trade-offs between existing service and new projects. To see the next generation of major transit infrastructure projects built more quickly and cost-effectively, the Bay Area will need to change the way it governs and plans them. A regional agency should oversee the planning and construction of the Bay Area’s transit infrastructure, ensuring great transit in the places it’s needed the most.

Price driving fairly.

For many in the Bay Area, driving is the default way to get around because it’s often easier and cheaper than any other option. Roads and parking are expensive to build, but they’re mostly free for drivers to use. This kind of free access exacerbates the serious costs that each driver imposes on other people: traffic and lost time; climate pollution and its resulting fires, floods and heat; local air pollution and the heart and lung disease it causes, especially for people with low incomes and people of color. To level the playing field between driving and other modes of travel, the price of driving needs to reflect the costs it imposes on others.

Explore the research:

A Regional Transit Coordinator for the Bay Area

How to Plan and Deliver Major Transit Projects in Less Time, for Less Money

A Fast and Reliable Regional Bus Network on Existing Freeway Lanes

Limiting the Costs That Driving Imposes on Others

Harnessing Private Mobility Services to Support the Public Good

IV. Conclusion

SPUR’s Regional Strategy presents a road map to a different future. We believe that the Bay Area can harness the same energy that saved the Bay, built BART, elected Harvey Milk, invented the microchip, pioneered the freeway removal movement, created social media and birthed marriage equality. We can evolve our region so that we preserve its physical beauty while highlighting and revering the beauty of its people. For other regions all over the world, we can provide a model of what a civic vision centered on equity, sustainability and prosperity can create.