Every time you ride BART, look out at San Francisco Bay or hike in the Bay Area hills, you are experiencing the product of regionalism.[1] In each case, civic activists and regional leaders helped deliver a solution to a regional problem, for the benefit of people far beyond their own individual community. Without the vision of these leaders and the institutions they created (mostly in the few decades after World War II), the Bay Area’s highways would be even more clogged with cars, San Francisco Bay would be a narrow industrialized shipping channel and the Bay Area hills would be full of subdivisions, not parks.

Despite the successes of the regionalism movement, many other challenges — most notably a chronic housing affordability crisis, an inadequate transportation system, growing climate threats and enduring income inequality — remain unsolved. These vexing issues have worsened in recent years, particularly during the economic boom. Jurisdictional and institutional fragmentation has increased, and the mechanisms that we have now to plan land use and transportation regionally are inadequate to effect change. There is no mechanism to implement any plan or vision across the region; plans can only be implemented locally across 101 cities and nine counties. Given the limited new building and investment of the past decades, there is no longer any slack in the region’s housing and transportation systems. The regional consequences of local events are intensified. In one example, when a 2012 fire at a construction site in West Oakland shut down BART for 12 hours, major portions of the region’s highway network totally broke down, as there was no alternative to the Transbay BART tube.

This is not for lack of effort. There are dozens of examples of Bay Area communities, public institutions and private companies seeking solutions to these collective challenges.

- Some cities are rewriting their general plans to allow more housing while other communities are resisting state requirements to do so.

- Voters in eight of the Bay Area’s nine counties have approved sales tax measures to spend billions on transportation. Yet those investments are not adding up to a functioning network, particularly for transit. Fragmented funding and governance yields fragmented systems or odd arrangements.[2]

- Some counties have also adopted sales taxes and bonds to fund affordable housing. But the annual revenue for affordable housing is far below the regional need as rents are rising far faster than wages and inflation.

- Major employers are also stepping up. In December 2017, Google (with the support of housing advocates) won approval at the Mountain View City Council to add nearly 10,000 housing units in the North Bayshore area, a move that will help turn a single-use office park into a mixed-use district. In 2016, Facebook provided funding for a Dumbarton Corridor Study and is now exploring a public-private rail transit project crossing the Bay.[3] But many other employers remain on the sidelines.

These and other actions show that, in some ways, we as a region are trying to work across jurisdictional and organizational silos and boundaries. But for every example of regionalism, there are counterexamples of parochial intransigence (as in 2013 when Palo Alto voters denied permits for an affordable housing development for seniors).[4]

Regional problems are not new, and the Bay Area’s regionalism movement has established many institutions and agencies whose mandate is to address regional issues. Yet the primary authority of these institutions is the power to say no. For example, regional agencies can block development on the Bay shoreline, limit permits to protect air quality or restrict regional funds toward undesirable transportation projects. Their primary authority is to achieve a regional outcome through blocking local actions that would potentially undermine a regional goal (like access to the Bay). But these regional institutions do not have the power to override local governments actions. They cannot compel local governments to approve needed housing or ensure transit has dedicated space on local streets. Instead, they are confronted with the frequent argument that there’s a compelling local reason to not do something.

This is in part by design. In order to protect local independence, many of our actions on regional issues are pursued at too small a geographic scale or through an institution with a narrow scope. And our regional institutions have insufficient legitimacy due in part to the lack of direct democratic accountability or general awareness by the public. Therefore, they cannot secure the authority to effectively tackle complex regional challenges.We believe it is time to change that. Today’s challenges necessitate elevating the role and authority of regional institutions. A strengthened civic movement towards regionalism can help achieve that.

500+ Governments: Fragmentation as the Essential Barrier to Regionalism

While the Bay Area is defined as the nine counties that touch the 1,600-square-mile San Francisco Bay, the region is culturally and politically fragmented. Most people identify more with their city than with the Bay Area writ large.

At the governmental level, there are 101 cities, nine counties, more than 200 school districts, 28 transit agencies and more than 200 special districts.[5] Sonoma County alone has just nine incorporated cities but 46 school districts and 45 special districts for services like fire, water, health care and parks and recreation. This level of fragmentation creates inefficiencies and higher costs through the duplication of functions as well as an exhausting coordination burden for each governmental unit.

To manage regional activities, there are five different primary regional agencies: MTC, ABAG, BAAQMD, BCDC and the Regional Water Quality Control Board. There is also a California Coastal Commission with authority to regulate coastal development. These are all largely single-purpose agencies that were designed to solve a specific issue like air or water quality and whose interests can be at odds with one other. In transportation, many regional decisions are in fact made by counties through their county agencies that control the expenditures from county sales tax measures. Land use decisions are left to the region’s 109 local governments.

While the county boundaries have not changed in more than a century, the city boundaries were adjusted significantly in the decades after World War II as new cities formed and older ones (such as San Jose, Hayward and Santa Rosa) expanded into unincorporated county land. But in recent decades, city boundaries have scarcely shifted, and the most recent newly incorporated city in the Bay Area is Oakley (Contra Costa County) in 1999.[6]

Origins of Regionalism in the Bay Area: 1920s to 1970s

During the early 20th century, regionalism emerges as a movement in response to the challenges with growth.

As early as the 1920s, nearly two-thirds of voters across nine cities in Contra Costa and Alameda counties (from Richmond to San Leandro) created the East Bay Municipal Utility District, an elected agency charged with supplying residential drinking water. To ensure that water quality would be protected, EBMUD opposed public access on its watershed lands. Ironically, the district’s exclusive focus on capturing and protecting water resources (along with other factors) led to the creation of the East Bay Regional Park District in 1934 so that parts of the East Bay hills would remain accessible public open space in perpetuity.

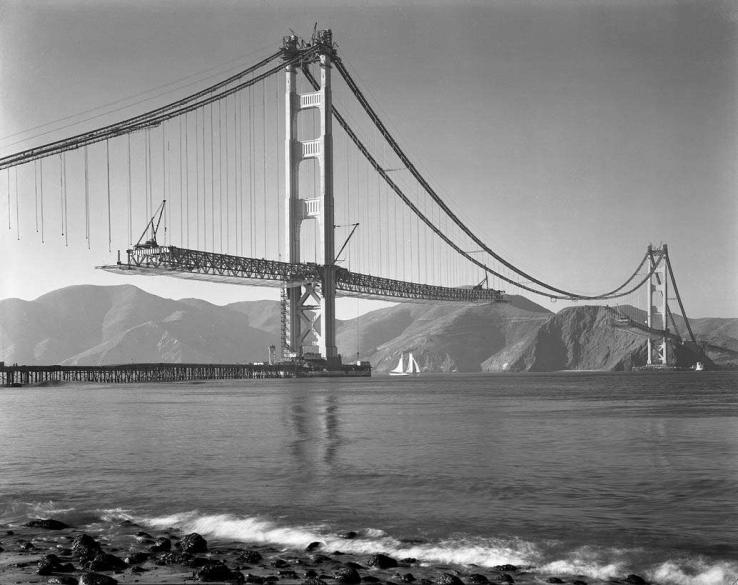

Also during this time, residents of Marin and San Francisco established the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District for the purposes of connecting San Francisco to the north for commerce and leisure. Regional leaders also came together to lobby for federal funds to build the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. Both bridges started construction in 1933. The Bay Bridge was completed in 1936, a year before the Golden Gate Bridge opened, and became the first route across the Bay other than ferries.

In the years during and immediately following World War II, the Bay Area boomed as hundreds of thousands of new residents arrived seeking opportunity. The region confronted challenges associated with rapid growth, particularly as communities were largely designed around the automobile. To manage the impacts of this growth, Bay Area leaders designed and launched more than half a dozen new governmental agencies, each designed solve a discrete problem:

- To deal with mobility challenges and growing congestion, Bay Area leaders proposed, designed and built a rail system connecting the East Bay and San Francisco (Bay Area Rapid Transit, or BART). When BART opened in the 1970s, it served fewer counties than when the system was conceived in the 1950s, yet it was nonetheless transformative in enabling the densification of downtown San Francisco.

-

To address growing pollution that crossed county boundaries, in 1955 the Bay Area established the nation’s first regional air pollution control agency, now called the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD).[7]

- In response to the problem of cities dumping their waste into the bay for territorial expansion, the state established a Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) in 1969, after a citizen-led “Save the Bay” movement that began in 1961.[8]

- To fight the creeping sprawl of development eating up rural areas and open space along the region’s hills, Bay Area activists organized and built a movement to support open space preservation and got the federal government to create the still-expanding Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

- To protect the coastline, Bay Area residents worked with supporters elsewhere in the state and established a powerful new state agency, the California Coastal Commission. Activists also fought to create the Point Reyes National Seashore.

Each agency was intended to solve a specific issue — or, more often, to block a regionally harmful outcome (sprawl, pollution, bay fill). The agencies were narrow in scope, and though several did directly challenge local control (namely BCDC and the Coastal Commission), they did not have the authority to require action or to achieve a particular positive outcome.

While many supported the creation of these single-purpose regional agencies, some activists also saw the need for a more comprehensive approach to managing interrelated problems across policy areas. In the late 1950s, these “metropolitan regionalists” called for a comprehensive new Bay Area agency — the Golden Gate Authority — to plan for and manage development by integrating land use, transportation and pollution control. Their vision of efficient, centrally managed economic development received political backing from big business, labor leaders and leading state politicians. In 1959, proponents introduced state legislation that strategically started with a focus on transportation. But the real goal was to create an agency empowered to expand operations to build infrastructure as well as industrial and residential development.

Many local politicians — including city council members and county commissioners — reacted with horror to the metropolitan regionalist vision. They feared a “supergovernment” could impose unwanted change on their constituents, and so they organized to defend “home rule” and to protect the autonomy of local governments by minimizing regional action and authority. In its place, mayors of dozens of Bay Area cities successfully advocated for the creation of a council of governments, which today is called the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG). This council of governments was and still is composed of local officials dedicated to strictly voluntary regional collaboration. They triumphed by getting the state legislature to kill the idea of a Golden Gate Authority in 1962. In the 1960s, leading environmentalists who also opposed the metropolitan vision joined forces with ABAG against any powerful regional government they feared would be designed to promote growth. By educating the public and elected officials, they believed that local government could be effectively harnessed to protect nature and preserve open space. While many local governments did embrace environmental goals and open space preservation, this form of voluntary and local government-led regional planning did not lead to sufficient zoned capacity for housing nor local support for dense development (particularly jobs) around transit.

Retrenchment from Regionalism: 1970s to 1980s

In part as a result of the failures to create a more comprehensive regional government agency in the 1960s (as well as an embezzlement scandal at ABAG), the state established a new regional agency to manage the flow of transportation dollars to the Bay Area. This accident in history meant the Bay Area separated regional land use planning from transportation funding just when it mattered most.

The MTC began operations in 1971 and has since become the most powerful force in transportation funding and planning in the region. That today’s regional agencies struggle to grapple with urgent Bay Area problems reflects the triumph of the status quo and the failure of regionalists to lay a foundation for comprehensive regional action and authority.

By the mid-1970s, all the main regional governance institutions were in place in the Bay Area. Each was formed to solve or manage a specific set of issues. And most were established with some support from the state and/or federal government.

But the 1970s also marked the beginning of a retrenchment away from regionalism. Federal support for regionalism declined. In the late 1970s, the passage of Prop. 13 and the tax revolt in California signaled a political shift toward more limited government and greater local control.[9] The changes wrought by Proposition 13 tilted the land use incentive toward commercial development and saw the rise of major new suburban employment areas (such as Bishop Ranch and Hacienda Business Park in the East Bay) as well as the continued economic expansion in San Mateo and Santa Clara counties. Com-petition for jobs among cities became a dominant trend in economic development. Yet throughout this period, many in the region still called for regional solutions and the unfinished goal of a comprehensive institution to govern planning in the Bay Area.

A Renewed Regionalism? 1990s to Today

Since the 1990s there have been two key trends in regionalism. First, there has been a renewed civic interest in regionalism and unified regional action focused on smart growth and equity. Second, the regional agencies have responded by expanding their scope, most notably MTC investing transportation funds in housing as well as the staff integration of ABAG and MTC. (Actions by other regional agencies will be explored in future articles.)

On the civic front, the 1990s began with a range of voices calling in unison for meaningful regional reform.[10] This civic process, called Bay Vision 2020, brought together hundreds of regional leaders and proposed creating a new combined regional agency that would be made up of MTC, ABAG and BAAQMD (the Air District). While Bay Vision 2020 had significant regional support, in 1992 legislation designed to realize its goals failed by just a few votes in the state legislature.

Perhaps most significantly, the 1990s saw the rise of a larger movement calling for “smart growth,” a combination of better transit, improved investment in affordable housing and an emphasis on focusing more of the region’s growth around its transit infrastructure. This movement, which SPUR was very much part of, argued that decades of auto-dominated policies had put a strain on the region’s future and needed to be reversed. Smart growth and transit proponents, as well as a burgeoning equity movement, put a renewed light on the importance of regionalism and regional institutions.[11]

A major success of the civic effort around smart growth and equity was the greater integration of land use and transportation at MTC and ABAG. This was made possible in part by a new federal transportation bill in 1991 that directed more discretionary funds to metropolitan planning organizations (or MPOs), of which MTC is the Bay Area’s.[12]

Then, in response to the demands of the smart growth and equity movement, MTC made two major policy changes: investing some of its sizable (though still limited) transportation funds in land use planning and housing, and conditioning some of its discretionary transportation funds toward land use outcomes at the local level.

The investment in land use began in 1997, when MTC launched the Transportation for Livable Communities program to fund planning and capital work to support development near transit. Over five years, this program has provided $250 million in capital grants to localities. MTC has also worked directly with ABAG to launch programs to provide incentives to local governments to plan and approve development near transit. Referred to as Priority Development Areas (PDAs), the concept is intended as a bottom-up way to encourage communities to permit higher-density development around the region’s transit as cities had to voluntarily nominate areas of their own communities for additional growth. Efforts like these demonstrated a growing awareness of the need to incorporate local land use into transportation planning. Since 2005, MTC has provided more than $20 million in funding for local PDA plans, resulting in zoning for more than 65,000 homes and 100,000 jobs. Millions more have passed directly from MTC to county “congestion management agencies” (such as the Valley Transportation Authority or San Francisco County Transportation Authority) to distribute within their respective counties.

Another tool MTC employed to link transportation investments and local land use planning is to set performance goals to access transportation dollars. This idea of “conditioning “funds” began in 2001 when MTC adopted a transit-oriented development policy (Resolution 3434) that conditioned discretionary funds for transit expansions based on minimum zoning. MTC has expanded the conditioning of some transportation dollars (such as through the One Bay Area Grant program) based on local adoption of a Housing Element and complete streets policy as well as on past and future performance approving housing developments.

Both the regional investment in local planning and the conditioning of transportation funds were reinforced by state legislation, passed in 2008 (SB 375), mandating that metropolitan regions adopt an integrated land use and transportation plan (a Sustainable Communities Strategy) that projects a per capita reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (from less driving) and plans for sufficient housing to match the demand generated by the region’s economy.[13] The first such strategy in the Bay Area was Plan Bay Area, adopted in 2013 and updated in 2017.[14] Meeting SB 375 mandates for reducing greenhouse gas emissions required transportation plans that would lead to reduced driving and a land use vision that enabled more people to get around the region on transit.

Plan Bay Area, a state-mandated law that aims to integrate sustainable strategies to reduce transportation-related pollution and external greenhouse gas emission within the area’s nine counties, brings the Bay Area closer to a comprehensive approach to integrating land use and transportation. But the first two plans were produced and adopted by two agencies (ABAG and MTC) with somewhat different political and work cultures. In part as a result of tensions from the planning process, MTC leadership proposed merging all of ABAG’s planning staff into a unified regional planning department at MTC. That idea eventually expanded to include a complete staff integration of all of ABAG into MTC and the renaming of the staff as Bay Area Metro. This move, which took place between 2015 and 2017, was strongly supported by SPUR and other regional stakeholders.[15] It reflects a nearly 40-year goal to merge MTC and ABAG so that regional land use planning and transportation will be considered and planned together.

Where We Are today

In 2017, the staff of ABAG and MTC were integrated into a single staff under one executive director and two governing boards. Yet the agencies have yet to explore modifications to their governance. Within transportation funding, voters are stepping up and billions have been raised through county sales tax measures. But this fragmentation in funding makes it more difficult to achieve a unified cross-county vision for investment, as governance and decision-making is at the county level. MTC is also not sufficiently using its power to require coordination across various projects and transportation systems.

Yet as a reflection of the interest in further integration of land use and transportation, MTC and ABAG, in partnership with private sector, philanthropy and civic groups, have launched a regional initiative called CASA, a task force to look at housing solutions for the nine-county Bay Area.[16] While CASA is a meaningful step, the regional agencies have not yet increased their authority vis-à-vis local land use planning. The limitation on regional land use control means the regional agencies have to look for other hooks or incentives in order to achieve better land use outcomes at the local level. Changing that incentive structure remains the elusive goal of regionalists.

Arguably out of necessity, regionalism is gaining currency. Yet the housing and transportation problems are more acute than ever before. And fragmented funding and governance combined with limited authority in existing regional institutions remains a significant barrier.It is now time again for civic regionalism to propose solutions that match the scale of our challenges. A few ideas this movement for regionalism might consider include:

- Create a major regional housing program to capture and spend affordable housing funds regionally, not city by city.

- Require local plans adhere to the adopted regional plan (Plan Bay Area).

- Merge transit operators or establish a unified transit brand and customer experience to truly achieve seamless transit.

- Fully integrate climate adaption into land use and transportation planning, potentially through merging additional staff or governing boards.

The seeds of these ideas have been present for decades. But they will only succeed with strong support from the civic sector and a strengthened sense of regionalism among residents.

Endnotes

1 Regionalism, defined herein, is a movement that emerged in the early 20th century that sought to solve regional challenges through big moves like consolidating cities, building bridges and transit, securing natural resources, preserving open space and more.

2 In one example, Santa Clara County’s Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) is funding and building a BART extension into San Jose that BART will eventually operate. The two agencies have been at odds on key aspects of the project, including how it passes through downtown San Jose.

3 See: Facebook, SamTrans talk bridge partnership

4 See: Voters reject affordable senior housing project in Palo Alto

5 Analysis of school districts and special districts by SPUR. Special district data from the California Special District Association. See: Special Districts Map. School district data from the California Department of Education. See: Public Schools and Districts Data Files.

6 Prior to Oakley in Contra Costa County, the other most recent cities to incorporate in the Bay Area were Windsor in Sonoma and American Canyon in Napa, both of which incorporated in 1992.

7 See: History of the Air District.

8 See: History of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission

9 Although interestingly Prop. 13 gave more power to the state, as it limited local governments’ ability to modify their property tax rates.

10 In one action, regional nonprofit Greenbelt Alliance released a 1989 report titled “Reviving the Sustain-able Metropolis: Guiding Bay Area Conservation and Development into the 21st Century,” which focused on the importance of maintaining the regional identity with a necklace of urban centers around the Bay backed by open space. The report recognized that decentralization and auto-dominated suburbanization posed obstacles to the realization of that vision.

11 In fact, the last civic plan for the Bay Area was the well-regarded “Blueprint for a Sustainable Bay Area,” first released by Urban Ecology in 1996, which focused on encouraging single-occupant automobile drivers to take transit and other modes and to help revitalize communities in the region’s core.

12 The 1991 passage in Congress of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) meant the federal government directed more funds directly to regions rather than states. For the Bay Area, this meant the MTC had control over greater discretionary financial resources that could be leveraged as incentives to achieve particular policy outcomes

13 With the passage of SB 375, the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act, the state government further stepped in to make integrated land use and transportation planning a legal requirement for metropolitan regions in California.

14 While the first Plan Bay Area was adopted in 2013, it built on more than a decade of vision-planning efforts that sought to propose where the region should grow in a way that reduced our overall reliance on driving. The first major such regional planning effort was the Livability Footprint Project, which was led by MTC and ABAG and completed in 2002. This was not a regional plan per se, but it was nonetheless a major regional undertaking with well-attended convenings in every county in the Bay Area where participants discussed tradeoffs between jobs, housing and transportation projects. The more traditional Regional Transportation Plans, which MTC had been preparing for decades, were often described as an exercise in stapling together each county’s respective transportation plans with limited regional oversight. In addition to the land use focus from SB 375, MTC has been doing more objective analysis of transportation projects to ensure that they provide good benefits for their costs and help meet some of the region’s targets around public health, equity and economic growth.

15 See: Merge regional agencies to address common problems

16 CASA is not an acronym and stands for “the Committee to House the Bay Area.” See: CASA – The Committee to House the Bay Area